Analytic Hierarchy Process: Difference between revisions

imported>Larry Sanger (moving author-directed note to talk page) |

imported>Larry Sanger (→Underlying philosophy: Moving comments to talk page) |

||

| Line 9: | Line 9: | ||

==Underlying philosophy== | ==Underlying philosophy== | ||

<font color=red>'''''Under Construction'''''</font><BR> | <font color=red>'''''Under Construction'''''</font><BR> | ||

In the 1960s, the U.S. and the Soviet Union were negotiating to reduce the number of nuclear weapons held by both parties. On the U.S. side, the study of this problem was assigned to the State Department's Arms Control and Disarmament Agency. Over several years, this agency spent significant resources to tap the knowledge of some of the world's leading thinkers in mathematical economics, utility theory, game theory, and conflict resolution. It was found, unfortunately, that negotiators and other nontechnical people could neither learn nor apply the findings of these scholars. There was a two culture chasm in thought and language that could not be bridged. | In the 1960s, the U.S. and the Soviet Union were negotiating to reduce the number of nuclear weapons held by both parties. On the U.S. side, the study of this problem was assigned to the State Department's Arms Control and Disarmament Agency. Over several years, this agency spent significant resources to tap the knowledge of some of the world's leading thinkers in mathematical economics, utility theory, game theory, and conflict resolution. It was found, unfortunately, that negotiators and other nontechnical people could neither learn nor apply the findings of these scholars. There was a two culture chasm in thought and language that could not be bridged. | ||

Revision as of 18:10, 18 October 2007

The Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP) is a technique for dealing with complex decisions where a number of competing factors demand consideration. It is especially suited to problems with high stakes, involving human perceptions and judgments, whose resolutions have long-term repercussions.[1] AHP provides a comprehensive and rational framework for structuring a problem, for representing its elements and quantifying them, for relating those elements to overall goals, and for evaluating alternative solutions.

While it can be used by individuals working on straightforward problems, AHP is most commonly applied where teams of people are working on highly complex situations, particularly where some of the elements are difficult to quantify. Computer software is available to assist in the application of the process.

Developed in the 1970s by mathematician Thomas L. Saaty, AHP has been applied worldwide, in a wide variety of decision situations, in fields such as government, business, industry, healthcare, quality, and education.

Underlying philosophy

Under Construction

In the 1960s, the U.S. and the Soviet Union were negotiating to reduce the number of nuclear weapons held by both parties. On the U.S. side, the study of this problem was assigned to the State Department's Arms Control and Disarmament Agency. Over several years, this agency spent significant resources to tap the knowledge of some of the world's leading thinkers in mathematical economics, utility theory, game theory, and conflict resolution. It was found, unfortunately, that negotiators and other nontechnical people could neither learn nor apply the findings of these scholars. There was a two culture chasm in thought and language that could not be bridged.

The quest to understand and bridge such chasms led to the search for a decision making method that

- Does not require inordinate specialization to master

- Can incorporate both intuitive and analytical judgments

- Is adaptable to both groups and individuals, and

- Encourages compromise and consensus building

Three principles guide one in using the AHP:

- Decomposition

- Comparative judgments

- Synthesis of priorities

Decision making is a process that involves these steps:

- Structure a problem as a hierarchy or as a system with dependence loops

- Elicit judgments that reflect ideas, feelings or emotions

- Represent those judgments with meaningful numbers

- Use these numbers to calculate the priorities of the elements in the hierarchy

- Synthesize these results to determine an overall outcome

- Analyze the sensitivity to changes in judgment

People find AHP easy to use because:

- People find it natural and ar usually attracted rather than alienated by it

- It does not need advanced technical knowledge and nearly everyone can use it

- It takes into consideration judgments based on people's feelings and emotions as well as their thoughts

- It deals with intangibles side by side with tangibles. What we perceive with the senses is dealt with by the mind in a similar way to what we feel.

- It derives scales through reciprocal comparison rather than by assigning numbers pulled from the mind directly

- It does not take for granted the measurements on scales, but asks that scale values be interpreted according to the values of the problem

- It relies on simple-to-elaborate hierarchic structures to represent decision problems. With such appropriate representation, it is able to handle problems of risk, conflict, and prediction

- It can be used to make direct resource allocation, benefit/cost analysis, resolve conflicts, design and optimize systems

- It is an approach that describes how good decisions are made rather than prescribes how they should be made. No one living at a certain time knows what is good for people for all time.

- It provides a simple and effective procedure to arrive at an answer, even in group decision making where diverse expertise and preferences must be considered

- It can be applied in negotiating conflicts by focusing on relations between relative benefits to costs for each of the parties

Uses and applications

The applications of AHP to complex decision situations number in the thousands,[2] typically where problems are important and complex. Many such applications are never reported to the outside world, because they take place at high levels of large organizations, where security and privacy considerations prohibit their disclosure. But some uses of AHP are discussed in the literature. Recently these have included:

- Deciding how best to reduce the impact of global climate change (Fondazione Eni Enrico Mattei)[3]

- Quantifying the overall quality of software systems (Microsoft Corporation)[4]

- Selecting university faculty (Bloomsburg University of Pennsylvania) [5]

- Deciding where to locate offshore manufacturing plants (University of Cambridge)[6]

- Assessing risk in operating cross-country petroleum pipelines (American Society of Civil Engineers)[7]

- Deciding how best to manage U.S. watersheds (U.S. Department of Agriculture)[2]

AHP was recently applied to a project that uses video footage to assess the condition of highways in Virginia. Highway engineers first used it to determine the optimum scope of the project, then to justify its budget to lawmakers.[8]

The process is widely used in countries around the world. At a recent international conference on AHP, over 90 papers were presented from 19 countries, including the U.S., Germany, Japan, Chile, Malaysia, and Nepal. Topics covered ranged from Establishing Payment Standards for Surgical Specialists, to Strategic Technology Roadmapping, to Infrastructure Reconstruction in Devastated Countries.[9] AHP was introduced in China in 1982, and its application has expanded greatly since then—its methods are highly compatible with the traditional Chinese decision making framework, and it has been used for many decisions in the fields of economics, energy, management, environment, traffic, agriculture, industry, and the military.[10]

Though using AHP requires no specialized academic training, the subject is widely taught at the university level—one AHP software provider lists over a hundred colleges and universities among its clients.[11] AHP is considered an important subject in many institutions of higher learning, including schools of engineering[12] and graduate schools of business.[13] AHP is also an important subject in the quality field, and is taught in many specialized courses including Six Sigma and QFD.[14][15][16]

In China, nearly a hundred schools offer courses in AHP, and many doctoral students choose AHP as the subject of their research and dissertations. Over 900 papers have been published on the subject in that country, and there is at least one Chinese scholarly journal devoted exclusively to AHP.[10]

Description of the process

The introductory material for this section is Under Construction

AHP is a method that breaks complexity into manageable pieces, works with each piece, then collectively evaluates all the pieces. The steps are...

Though the AHP can be used by an individual, our discussion will assume it's used by a group.

Brainstorming goes on a lot in the early stages.

We say "decision problem," but there might be a more general term.

Make it clear that this is a simplified description, and that it is based on previously published information, especially Decision Making for Leaders, but also including lots and lots of other books and articles.

Include a summary of the main steps in the process (the steps further described below).

Hello again, Lou....

Model the problem as a hierarchy

The first step in the Analytic Hierarchy Process is to model the problem as a hierarchy. In doing this, participants explore the aspects of the problem at levels from general to detailed, then express it in the multileveled way that the AHP requires. As they work to build the hierarchy, they increase their understanding of the problem, of its context, and of each other's thoughts and feelings about both.[17]

Hierarchies defined

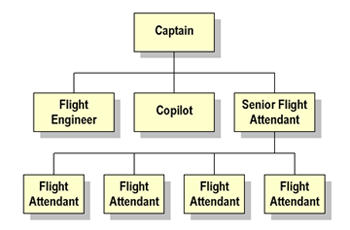

A hierarchy is a system of ranking and organizing people, things, ideas, etc., where each element of the system, except for the top one, is subordinate to a single other element. Diagrams of hierarchies are often shaped roughly like pyramids, but other than having a single element at the top, there is nothing necessarily pyramid-shaped about a hierarchy.

Human organizations are often structured as hierarchies. In the airliner example shown to the right, the hierarchical system is used for assigning responsibilities, exercising leadership, and facilitating communication.

Familiar hierarchies of "things" include a desktop computer's tower unit at the "top," with its subordinate monitor, keyboard, and mouse. Inside the tower is another hierarchy, with the top level motherboard and its subordinate hard drive(s), CD-ROM drive, and sometimes a floppy drive or DVD writer.

In the world of ideas, we use hierarchies to help us acquire detailed knowledge of complex reality: we structure the reality into its constituent parts, and these in turn into their own constituent parts, proceeding down the hierarchy as many levels as we care to. At each step, we focus on understanding a single component of the whole, temporarily disregarding the other components at this and all other levels. As we go through this process, we increase our understanding of whatever reality we are studying.

Think of the hierarchy that medical students use while learning anatomy—they separately consider the musculoskeletal system (including parts and subparts like the hand and its constituent muscles and bones), the circulatory system (and its many levels and branches), the nervous system (and its numerous components and subsystems), etc., until they've covered all the systems and the important subdivisions of each. Advanced students continue the subdivision all the way to the level of the cell or molecule. In the end, the students understand the "big picture" and a considerable number of its details. Not only that, but they understand the relation of the individual parts to the whole. By working hierarchically, they've gained a comprehensive understanding of anatomy.

Similarly, when we approach a complex decision problem, we can use a hierarchy to integrate large amounts of information into our understanding of the situation. As we build this information structure, we form a better and better picture of the problem as a whole.

AHP hierarchies explained

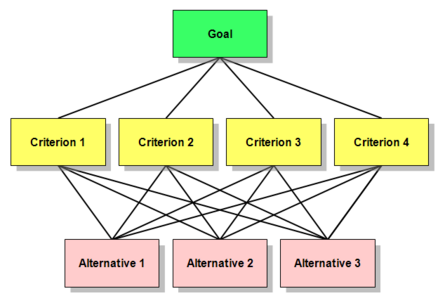

An AHP hierarchy is a structured means of describing the problem at hand. It consists of an overall goal, a group of options or alternatives for reaching the goal, and a group of factors or criteria that relate the alternatives to the goal. In most cases the criteria are further broken down into subcriteria, sub-subcriteria, and so on, in as many levels as the problem requires.

The hierarchy can be visualized as a diagram like the one below, with the goal at the top, the alternatives at the bottom, and the criteria filling up the middle.

The specifics of any AHP hierarchy will depend not only on the nature of the problem at hand, but also on the knowledge, judgments, values, opinions, needs, wants, etc. of the participants in the process.

As the AHP proceeds through its other steps, the hierarchy can be changed to accommodate newly-thought-of criteria or criteria not originally considered to be important; alternatives can also be added, deleted, or changed.

A simple example

In an AHP hierarchy for the simple case of buying a vehicle, the goal might be to choose the best car for the Jones family. The criteria to be considered might be cost, safety, style, and capacity. The cost criterion might be subdivided into purchase price, fuel costs, maintenance costs, and resale value. Capacity might be subdivided into cargo capacity and passenger capacity. The alternatives for the family, which for personal reasons always buys Hondas, might be the Accord Sedan, Accord Hybrid Sedan, Pilot SUV, CR-V SUV, Element SUV, and Odyssey Minivan.

The Jones' hierarchy could be diagrammed like this:

Some simple terms apply to the boxes in the diagram above. Each of the boxes is called a node. The boxes descending from any node are called its children. The node from which a child node descends is called its parent. Applying these definitions, the four Criteria are children of the Goal. The Goal is the parent of each of the four Criteria. Cargo Capacity and Passenger Capacity are the children of their parent, the Capacity criterion. ROZANN: Are the alternatives (below) children of the nodes directly above them? Do we refer to grandchildren, etc.?

As they build their hierarchy, the Joneses should investigate the values or measurements of the different elements that make it up. If there are published safety ratings, for example, or manufacturer's specs for cargo capacity, they should be gathered as part of the process. This information will be needed later, when the criteria and alternatives are evaluated. Information about the Jones' alternatives, including color photos, can be found HERE.

Note that the measurements for some criteria, such as purchase price, can be stated with absolute certainty. Others, such as resale value, must be estimated, so must be stated with somewhat less confidence. Still others, such as style, are really in the eye of the beholder and are hard to state quantitatively at all. The AHP can accommodate all these types of criteria, even when they are present in a single problem.

Also note that the structure of the vehicle-buying hierarchy might be different for other families (ones who don't limit themselves to Hondas, or who care nothing about style, or who drive less than 5,000 miles a year, etc.). It would definitely be different for a 25-year-old playboy who has millions to spend on cars, knows he will never have a wreck, and is intensely interested in speed, handling, and the numerous aspects of style.

Additional information. More information about hierarchies, including further reading and some complex real-world examples, can be found HERE.

Establish Priorities

Once the hierarchy has been constructed, the participants use AHP to establish priorities for all its nodes. In doing so, information is elicited from the participants and processed mathematically. This activity is somewhat complex, and the participants have many options on the road to completing it. This and the following sections describe a simple, straightforward example of establishing priorities.

As our first step, we will define priorities and show how they interact.

Priorities are numbers associated with the nodes of the hierarchy. By definition, the priority of the Goal is 1.000. The priorities of the Criteria (which are the children of the Goal) can vary in magnitude, but will always add up to 1.000. The priorities of the children of any Criterion can also vary but will always add up to 1.000, as will those of their own children, and so on down the hierarchy.

This illustration shows some priorities for the Jones car buying hierarchy. We'll say more about them in a moment. For now, just observe that the priorities of the children of each parent node add up to 1.000, and that there are three such groups of children in the illustration.

If you understand what has been said so far, you will see that if we were tp add a "Handling" criterion to this hierarchy, giving it five Criteria instead of four, the priority for each would be .200. You will also know that if the Safety criterion had three children, each of them would have a priority of .333.

In our example as it stands, the priorities within every group of child nodes are equal. In this situation, the priorities are called default priorities. As the analytic hierarchy process continues, the default priorities will change to reflect our judgments about the various items in each group.

As you may have guessed by now, the priorities indicate the relative weights given to the items in a given group of nodes. Depending on the problem at hand, "weight" can refer to importance, or preference, or likelihood, or whatever factor is being considered by the participants.

If all the priorities in a group are equal, each member has equal weight. If one of the priorities is two times another, or three, (or whatever), that member has two, or three, (or whatever) times the weight of the other one. For example, if we judge cargo capacity to be three times as important as passenger capacity, cargo capacity's new priority will be .750, and passenger capacity's priority will be .250, because .750 = 3 × .250, and .750 + .250 = 1.000. (Don't worry—the AHP software keeps track of all this.)

AHP priorities have another important feature. The priority of any child node represents its contribution to the priority of its parent. In the diagram above, Cost, Safety, Style and Capacity each contribute .250 of the 1.000 priority of the Goal. Cargo capacity and passenger capacity each contribute half of the priority belonging to the Capacity criterion. Working through the arithmetic, Passenger Capacity contributes .500 × .250 = .125 of the 1.000 priority of the Goal.

As we move ahead through the Analytical Hierarchy Process, the priorities will change but will still add to 1.000 for each group of child nodes.

Make judgments

Under Construction

Establish priorities for the elements of the hierarchy.

Includes inputting data.

Be careful about data. There are scales involved. Some are meaningful to us and the problem, some are not.

This includes the consistency check step (repeated at every level)

(Rozann: pairwise comparisons using judgment)

Derive priorities

Under Construction

This is done by "AHP Magic Math."

It turns your pairwise comparisons of items at one level into weights for the items at that level.

Maybe we are "developing" priorities, or "calculating" them, or ????

Synthesize priorities throughout the structure

Under Construction

More "AHP Magic Math"

It takes the priorities for the various items at the various levels and turns them into one big integrated set of priorities for the whole hierarchy.

Check sensitivity

Under Construction

Take a look at what would happen if your judgments changed.

Using AHP with groups

Under Construction

When you get to this part, go through the whole article and harmonize "user", "participants", etc.

Criticisms and drawbacks

Under Construction

See also

Multi Criteria Decision Making

References

- ↑ Bhushan, Navneet; Kanwal Rai (January, 2004). Strategic Decision Making: Applying the Analytic Hierarchy Process. London: Springer-Verlag. ISBN 1-8523375-6-7.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 de Steiguer, J.E. (October, 2003), The Analytic Hierarchy Process as a Means for Integrated Watershed Management, in Renard, Kenneth G., First Interagency Conference on Research on the Watersheds, Benson, Arizona: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service, at 736-740

- ↑ Berrittella, M. (January, 2007), An Analytic Hierarchy Process for the Evaluation of Transport Policies to Reduce Climate Change Impacts, Fondazione Eni Enrico Mattei (Milano)

- ↑ McCaffrey, James (June, 2005). "Test Run: The Analytic Hierarchy Process". MSDN Magazine. Retrieved on 2007-08-21.

- ↑ Grandzol, John R. (August, 2005). "Improving the Faculty Selection Process in Higher Education: A Case for the Analytic Hierarchy Process". IR Applications 6. Retrieved on 2007-08-21.

- ↑ Atthirawong, Walailak (September, 2002), An Application of the Analytical Hierarchy Process to International Location Decision-Making, in Gregory, Mike, Proceedings of The 7th Annual Cambridge International Manufacturing Symposium: Restructuring Global Manufacturing, Cambridge, England: University of Cambridge, at 1-18

- ↑ Dey, Prasanta Kumar (November, 2003). "Analytic Hierarchy Process Analyzes Risk of Operating Cross-Country Petroleum Pipelines in India". Natural Hazards Review 4 (4): 213-221. Retrieved on 2007-08-20.

- ↑ Larson, Charles D. (January, 2007), Application of the Analytic Hierarchy Process to Select Project Scope for Videologging and Pavement Condition Data Collection, 86th Annual Meeting Compendium of Papers CD-ROM, Transportation Research Board of the National Academies

- ↑ Participant Names and Papers, ISAHP 2005, Honolulu, Hawaii (July, 2005). Retrieved on 2007-08-22.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Sun, Hongkai (July, 2005), AHP in China, in Levy, Jason, Proceedings of the 8th International Symposium on the Analytic Hierarchy Process, Honolulu, Hawaii

- ↑ List of Expert Choice education clients. Retrieved on 2007-08-23.

- ↑ Drake, P.R. (1998). "Using the Analytic Hierarchy Process in Engineering Education". International Journal of Engineering Education 14 (3): 191-196. Retrieved on 2007-08-20.

- ↑ Bodin, Lawrence; Saul I. Gass (January, 2004). "Exercises for Teaching the Analytic Hierarchy Process". INFORMS Transactions on Education 4 (2). Retrieved on 2007-08-20.

- ↑ Hallowell, David L. (January, 2005). "Analytical Hierarchy Process (AHP) -- Getting Oriented". iSixSigma.com. Retrieved on 2007-08-21.

- ↑ "Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP)". QFD Institute. Retrieved on 2007-08-21.

- ↑ "Analytical Hierarchy Process: Overview". TheQualityPortal.com. Retrieved on 2007-08-21.

- ↑ Saaty, Thomas L. (1999-05-01). Decision Making for Leaders: The Analytic Hierarchy Process for Decisions in a Complex World. Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania: RWS Publications. ISBN 0-9620317-8-X. (This book is the primary source for the section in which it is cited.)