Poland: Difference between revisions

imported>Aleksander Stos m (→Economy: typos) |

imported>Richard Jensen (→Economy: small rephrase) |

||

| Line 196: | Line 196: | ||

The successful rebuilding after World War II of the nearly totally destroyed economy was followed by promotion of the Stalinist economic system. Its promoters claimed that it was necessary to accelerate economic growth and build a modern industrial base, though Poland lagged far behind western Europe in industrialization. In 1949 Poland joined the Soviet-dominated Council for Mutual Economic Assistance ([[COMECON]]). The effect was to interlock the Policsh economy with the economically backward Russian economy, and impede long-term growth. However, as farmers moved to more efficient factory jobs the economy did grow. The Soviet-type system was unable to collect or process accurate information centrally--prices did not reflect costs but were political devices negotiated by power brokers inside the Communist party. Centralization was inefficient, necessitating reform moves by Gomulka after 1956. These reforms were cautious, partial, and revocable and a recentralization of the economy took place during the 1960s.<ref> Lukowski and Zawadzki, ''Concise History'' ch. 7</ref> | The successful rebuilding after World War II of the nearly totally destroyed economy was followed by promotion of the Stalinist economic system. Its promoters claimed that it was necessary to accelerate economic growth and build a modern industrial base, though Poland lagged far behind western Europe in industrialization. In 1949 Poland joined the Soviet-dominated Council for Mutual Economic Assistance ([[COMECON]]). The effect was to interlock the Policsh economy with the economically backward Russian economy, and impede long-term growth. However, as farmers moved to more efficient factory jobs the economy did grow. The Soviet-type system was unable to collect or process accurate information centrally--prices did not reflect costs but were political devices negotiated by power brokers inside the Communist party. Centralization was inefficient, necessitating reform moves by Gomulka after 1956. These reforms were cautious, partial, and revocable and a recentralization of the economy took place during the 1960s.<ref> Lukowski and Zawadzki, ''Concise History'' ch. 7</ref> | ||

After 1945 modernization was accompanied by demands for more meat instead of bread by workers and farmers. The new demands on meat production could not be met because of the government's policy of investing in factories, not farms. | After 1945 modernization was accompanied by demands for more meat instead of bread by workers and farmers. The new demands on meat production could not be met because of the government's policy of investing in factories, not farms. People began meauring the performance of the government by the availability of meat; its performance was poor. Fearing mass protests, the Commuist party did not balance the market by raising prices but instead spent its money on subsidies to keep food prices low. Every attempt to raise prices caused grumbling; twice (1970, 1976) the government had to recerse the increases. By 1980 the scale of the imbalance of supply and demand led to meat rationing, a system that broke down in 1989, when in view of roundtable talks and rumors about anticipated price increases, the farmers simply ceased selling meat. The final solution was introducing market prices in the summer of 1989. The chronic imbalance of supply and demand can be related to the coexistence of a system of trading and distributing food products that from 1948 was state-owned and subjected to the directives of the Communist ideologues, while the agricultural sector comprising private farms that reacted to market stimuli.<ref> Jerzy Kochanowski, "'Jestesmy Juz Przyzwyczajeni' Prolegomena Do Spoleczno - Modernizacyjnych Kulis 'Problemu Miesnego' W Prl," ["We've Become Accustomed": Prolegomena to the Social Modernization Background of the "Meat Problem" in the People's Republic of Poland]. ''Przeglad Historyczny'' 2005 96(4): 587-605. Issn: 0033-2186 </ref> | ||

====Gomulka era: 1956-1970==== | ====Gomulka era: 1956-1970==== | ||

Revision as of 03:41, 20 September 2007

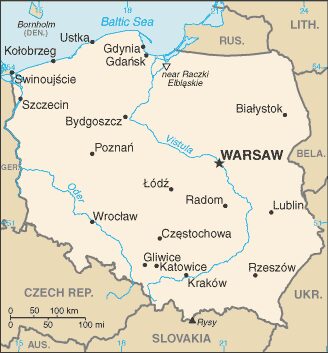

The Republic of Poland (Polish: Rzeczpospolita Polska) is a large Slavic nation in Central Europe. Its history stretches 1000 years, with interruptions when it was controlled or even divided up by powerful neighbors. It is a member of the European Union and NATO.

Geography

Poland is located in Central Europe and occupies a total area of 312,679 square kilometers. It is bordered by Belarus, the Czech Republic, Germany, Lithuania, a Russian exclave Kaliningrad Oblast, Slovakia, and Ukraine. Poland is predominantly open plains, with the natural borders of the Carpathian Mountains to the south and the Baltic Sea to the north.

Demography

Language, Religion, Culture

Religion was a mainstay of Polish identity for a thousand years. It was a refuge from Communist rule, and before that an act of defiance against Prussians and Russians. As the rest of Europe secularized in the late 20th century, the Catholic faith grew stronger in Poland, symbolized by the selection of Karol Cardinal Wojtyła, Archbishop of Kraków, as Pope John Paul II in 1978. Unlike the rest of Europe, the men of Poland were religious, as were the workers, peasants and middle classes. They disobeyed church edicts on birth control and abortion, but they practiced the rituals faithfully.[3] By the late 1980s, a third of all priests ordained in Europe were from Poland.[4]

Economy

Politics

History

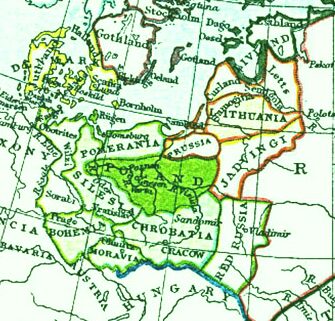

Poland has no natural boundaries, such as mountains or oceans, so its territory has expanded and contracted over the centuries, and (in political terms), it has even vanished from the map. The ethnic heartland of the Polish people, since the 7th century, has been the rich farmland between the Odra and Vistula rivers. The people named "polanians" or "people of the open fields." In 1492 (when it was united with Lithuania), the king controlled some 435,000 square miles. In 1634, with 387,000 square miles it was twice the size of France, and controlled 11 million people (most but not all speaking Polish). By 1773 the political realm was down to only 84,000 square miles, and Poland was too weak and inefficient to prevent its German and Russian neighbors from partitioning it up.[5]

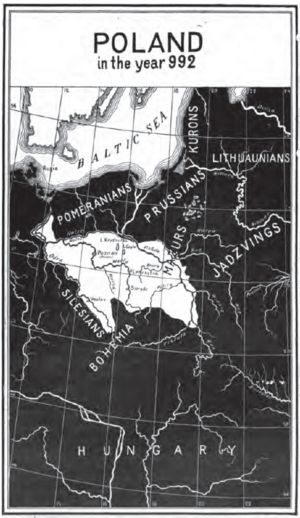

Piast era (963-1386)

Poland arose on the margins of old Roman Empire, at the frontier between West and East, facing the Rus' peoples and the expanding Byzantine civilization. The new Slavic land was underdeveloped in terms of economy and culture compared to lands to the west and south, especially German-speaking areas. The rivalry between the Germans and Slavs was a central theme from the 10th century to the 21st century. Medieval advances came late to Poland.

The first monarch of Poland was Mieszko I of the Piast dynasty, (ruled 960 to 992), a pagan chieftan with thousands of heavily armed mounted soldiers who gained control of territory stretching between the Oder and the Vistula rivers. Mieszko I married into the Bohemian German nobility, and became a Latin Rite Roman Catholic in 966, bringing in German clergymen and paying formal tribute to the Emperor Otto I. Thereby Poland gained access to superior military technology and links to the royal families and political and religious structures of the new Holy Roman Empire. By contrast the Ukrainians and Russians to the east chose Orthodox Christianity from Byzantium, became prey to the Mongol hordes, and skipped the Reformation, which gave them a very different, albeit also Slavic, outlook.[7]

Mieszko I expanded into German lands, conquering northwest into Pomerania in 988 and south into Moravia in 990. His son, Boleslaw I the Brave, became one of the outstanding kings (ruled 992-1025), and firmly established control from the Oder and the Neisse rivers to the Dnieper River and from Western Pomerania to the Carpathian Mountains. Taking advantage of the interregnum in Germany after the death of Otto III, Boleslaw had himself crowned king of Poland in 1025, refusing to recognize any German overlordship. He created the administrative structure needed for a large state, made the military more efficient, created monestaries, and in 1000 induced Otto III to set up the diocese of Gnesen that by the 12th century became the headquarters of a Polish church which reported to Rome. Weak sons succeeded Boleslaw, many of his conquests were lost, and the prestige of Poland declined while the power of the German Holy Roman emperors increased. Subsequently, the rulers of Poland were recognized only as dukes. Insurrection by pagans against Christianity massacred many priests but were suppressed in the late 1030s.

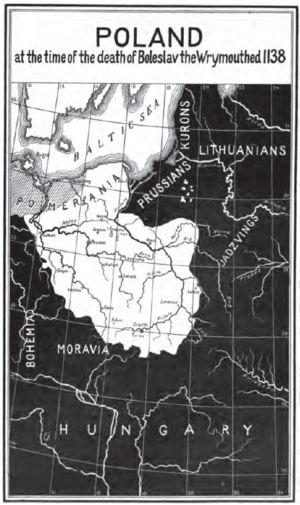

Boleslaw II (r.1058-79) proved one of the strongest rulers of Poland. He supported the pope against the emperor, established Kraków (Cracow) as the capital, formalized the roles of nobles and gentry, and pushed the peasants into serfdom. but battled against his own nobility. Boleslaw III ("Wry-mouth") (reigned 1102-38) defeated the Pomeranians and absorbed their lands. He defeated the emperor and stemmed German advances. But upon his death Poland was divided among his five sons, leading to years of internal conflict. The division led to political confusion as the number of feudatories increased. These feudatories soon refused to recognize the ruler in Kraków as "lord of all Poland," and eventually the princes and the Church succeeded in greatly reducing his power.

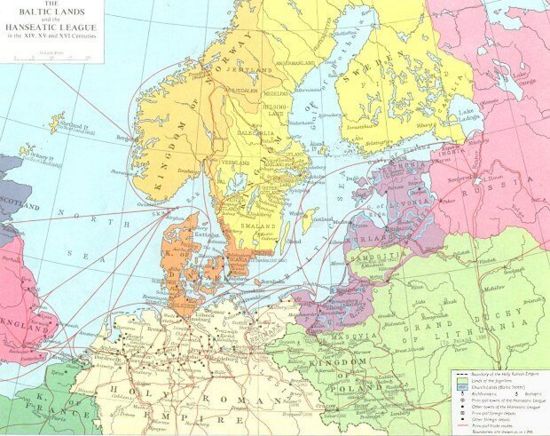

Teutonic Knights

In 1241 the massive Mongol-Tatar invasion on horseback from the east devastated large sections of Poland. Equally ruinous were the incessant raids from the north by the pagan Lithuanians and Prussians. To protect his domains, Duke Conrad of Mazovia in 1228 brought in the Teutonic Knights, a German-speaking military-religious crusading order. The Teutonic Knights crusaded against the pagan tribes and conquered most of what later became East Prussia. They settled German peasants in East Prussia and built 80 new towns and castles. By 1308 the powerful, expansionist state created by the Teutonic Knights, centered at their giant castle in Marienburg, cut off Poland's access to the Baltic Sea.

Breakdown of Central Authority

As a result of Poland's division into several principalities, the princes became increasingly dependent on the nobility and the gentry, whose support they needed for self-defense against external enemies. The decimation of the population by the Mongol-Tatars and the Lithuanians had led to an influx of German settlers, who either established themselves in cities governed under German law or received land as free peasants. By contrast, the Polish peasantry, like the peasantry throughout most of Europe at this time, became gradually enserfed and were tied to specific tracts of land.

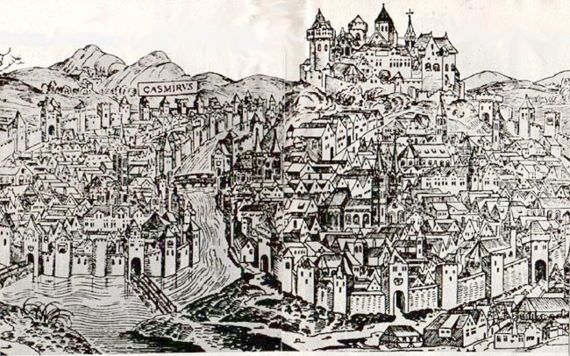

Casimir III and National Revival

The reunification of Poland[9] was achieved by Vladislav IV (Ladislas the Short or Wiadysiaw Lokietek) (r. 1305-33). Under the successful reign of his son, Casimir III the Great (r. 1333-1370), a national revival took place as Casimir consolidated royal power, reformed the administration and judiciary, set up a currency after the imperial pattern, promulgated a code of laws known as the Statutes of Wíslica (1347), improved the lot of the peasants, and allowed the Jews, fleeing persecution in Western Europe, to settle in Poland. He was unable to secure access to the Baltic and lost Silesia to Bohemia; but he gained territory to the south-east.[10] He founded the first Polish university in Krakow in 1364. Casimir was succeeded by his nephew, Louis I (r. 1370-1382), who was more interested in his Jungarian kingdom and gave away more privileges to the Polish nobles by the Covenant of Koszyce (1374), notably the right to pay no taxes beyond a certain sum without their consent. The Piast era represents to Polish nationalists the flourishing of Polish nationalism, especially anti-German in nature; a patriotic desire that Poles should be ruled by Poles; and inclusion of the peasantry as honored and equal participants in the political nation.

Jagellonian Era (1386-1572)

The death of King Louis marked the end of the Piast era. Jagello, grand duke of Lithuania, married Queen Jadwiga and ruled Poland as Vladislav II (r. 1386-1434). He reoriented the nation to the east and the Baltics, made Lithuania Christian and founded one of the greatest dynasties in Europe. The lands of Poland and Lithuania were joined into a powerful personal union. In 1410 the Poles and the Lithuanians defeated and crippled the Teutonic Order at Grunwald (See Battle of Tannenberg). In 1413 they confirmed the union and Lithuania established institutions modeled on those of Poland. Casimir IV (r. 1447-1492) tried to curb the power of the nobles, but lost and was forced to confirm their privileges and the prerogatives of the parliament, which was composed of the high clergy, the nobility, and the gentry. In 1454 at Nieszawa he granted the nobles a charter regarded as their Magna Carta. He gained the power to name the bishops. His war with the Teutonic Knights from 1454 to 1466 ended in a Polish triumph, and the return of Pomerania and Danzig (Gdansk) to Poland. Thus Polish access to the Baltic was restored.

The Golden Age of Poland

The 16th century was the golden age in Polish history. It was one of the largest countries in Europe, and dominated east-central Europe, including Ukraine. Its culture flourished. However, the emergence of centrally organized expanding Muscovy in the east, the process of unification and expansion of Brandenburg and Prussia in the north and west, and the still dynamic Ottoman Empire in the south represented great and growing dangers for a country whose monarchy was slowly but incessantly weakening. The lesser nobility kept gaining power and blocked efforts by the king to strengthen royal power, upgrade the army or reform the administration. In 1505 at Radom, King Alexander I (r. 1501-1506) had to accept the statute "Nihil Novi" by which the diet (parliament) obtained an equal voice with the crown in all executive matters and a veto in all matters concerning the nobility. The parliament consisted of two chambers--the Sejm, in which the gentry was represented, and the Senate, representing the nobility and high clergy. Poland's long and open frontiers and frequent wars meant that a trained standing army was necessary to preserve the existence of the Polish kingdom. The monarchs themselves lacked the resources needed to maintain such an army. Therefore, they had to get the approval of the parliament for any major expenditure. The nobility and gentry, however, insisted on new privileges in exchange for their contributions; thus Poland developed a sort of "gentry republic," with the richest and most powerful nobles exercising an ever-growing influence.

King Sigismund I (Zygmunt) (1467-1548, reigned 1506-1548) set up the legal codes that formalized serfdom, locking the peasants into the estates of nobles. After marrying Bona Sforza of a leading Italian family he sparked a cultural renaissance by patronizing the arts and bringing in Italian architects, artists as well as chefs who introduced Italian cuisine.[11] Sigismund II Augustus ((1520-72, reigned 1548-1572) was the last of the Jagellonian kings. Kraków became one of the great European centers of humanist scholarship, Renaissance architecture and art, Polish poetry and prose, and, for a few years, of the Reformation. Poland and the neighboring Central European region offered a wide range of individual mobility and the possibility of intercultural exchange in its cities for persons aside from the nobility. The Thurzó family reached its peak during the time the Jagellonian dynasty sat on the thrones of Poland and Lithuania, Bohemia, and Hungary, and while Cracow enjoyed prestige as one of the most important centers of this golden age.

It was in Kraków (Cracow) that the rise of the Thurzó family, originally from the Spis region, began, and it in turn influenced Cracow's development into a center of science and the arts and letters. The Thurzós' commitment to the early capitalist economy, politics, the Catholic Church, and the arts turned this family into one of the most powerful in East Central Europe. Its role may well be compared to that of the Medici in Italy and France and of the Fugger family in the southern regions of Germany. Outstanding individuals of the Thurzó family, including Johann Thurzó (1437-1508) and his sons Johann (1466-1520), bishop of Breslau/Wroclaw, and Stanislaus (1471-1540), bishop of Olmütz/Olomouc, were simultaneously merchants, politicians, and patrons of the arts and helped transmit the Renaissance through East Central Europe. The most lasting contribution of the Thurzó family came in the sphere of "intercultural communications": the introduction and transmission of new concepts in the arts, the exchange of and between scientists, and the establishment of contacts between different social groups. It is also in this sphere that both the uniqueness of the East Central European metropolitan cities and the outstanding influence of the Thurzó family are to be traced.[12]

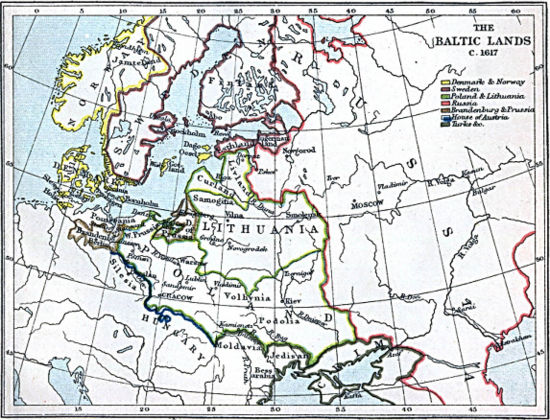

Polish-Lithuanian Union

In 1525, Albert of Brandenburg, the grand master of the Teutonic Knights, was converted to Lutheranism, and King Sigismund I allowed him to transform the possessions of the Teutonic Order into a hereditary duchy of Prussia under Polish suzerainty. In 1522 Poland was forced to cede some Lithuanian provinces to Muscovy (later Russia). With a deterioration of Habsburg-Jagellonian relations, the Polish king strengthened his hand at home, by clearing off foreign policy problems with Turkey, Russia, and Austria. The Treaty of 1549 constituted a compromise over Prussia, which remained with Poland for the time being, but would go to the Holy Roman Empire after the death of Sigismund I in 1548. Poles admired Sigismund I -- he was handsome, strong, wise, pious and just, attached to peace, intelligent and well educated; he lacked energy and vision, however. During the rule of Sigismund II Augustus ((1520-72, reigned 1548-1572), Poland acquired Livonia (now part of Latvia and Estonia) as a fief of the crown. The 10 year conflict that followed Ivan the Terrible's conquest of most of Livonia sapped Poland's energies but it did produce a great political triumph, signed in Lublin in 1569, which changed the old Polish-Lithuanian personal union into an organic and permanent union. From then on, the same ruler was to be elected by the nobility in each country; there was to be a single Diet, a common currency and laws, and, finally, religious toleration. The last point was significant because large areas conquered in the past by the Lithuanian rulers were inhabited by Orthodox Christians. The Poles were still able to hold their own in the wars with Czar Ivan the Terrible of Russia.

Poland under the reigns of Sigismund I (1506-1548) and Sigismund II (1548-1572) was marked by the struggle of the middle gentry for their share in control of the state. The kings ensured the effective execution of policy by manipulation of political institutions, including the appointment of officials; elections to and debating procedures in the Sejm; political propaganda accompanying government actions; and appealing to the gentry's economic interests and ideological values. The result was that coercion and repressive measures were rarely resorted to, and the second half of the 16th century was the only time in the history of prepartition Poland when the "democracy of the gentry" was properly implemented.[14]

Protestant Reformation

The Protestant Reformation reached Poland by the 1520s, converting many urban Germans and merchants to Lutheranism, especially in West Prussian cities like Danzig and Thorn. Sigismund I, a loyal Catholic, beheaded the Lutheran leadership in Danzig but was unable to change the popular mood there. In 1525, Albert Hohenzollern, Grand-Master of the Order of the Teutonic Knights, left the Roman Church, accepted Lutheranism, secularized the possessions of the Order with the consent of King Sigismund I, and by the 1525 treaty of Cracow became the secular hereditary ruler of the vassal Duchy of East Prussia with a right to the first seat in the Polish Senate. Lutheranism thus spread to the two German speaking Polish provinces of West Prussia and East Prussia. In Cracow the king threatened to execute heretics, and began house-to-house searches for Lutheran pamphlets, but Catholic bishops and priests seemed dilatory, because the Church lacked power over the nobles who tolerated or encouraged Protestantism. After 1540 the Calvinists arrived, converting more Poles to Protestantism, using pamphlets written in the vernacular (Polish) rather than Latin, and organizing their own synod in Little Poland, while the Bohemian Brethren were active in Great Poland.. When Sigismund II Augustus replaced his father in 1548 he was much more tolerant and sought a compromise; indeed Protestants were quietly active in high court circles. From 1552 to 1565 the Protestants dominated all the Diets, invariably electing one of their own as president of the Chamber of Deputies. The religious issue now reached center stage. The Diet of 1555 made Protestantism legally recognized, receiving full freedom of worship and the legal right to all the church property already in the hands of Protestants. Meanwhile in the 1560s and 1570s the Protestants became more splintered with the rise of the Unitarians[15]; Lutherans united with the Calvinists in 1570, but both rejected union with the Unitarians. The lesser nobility rejected Catholic church jurisdiction and cut back on tithes and payments.

Rome became alarmed as Poland drifted away and began a counter-reformation. It realized conditions were bad among the clergy and needed reform. [16] Rome told the Catholic bishops to live more simply and to give more personal attention to their dioceses, and to reform and dignify the priesthood. The Jesuits played a powerful role, establishing schools with a special appeal to the sons of the poorer gentry. The Catholics raised money for the king's wars. The counter-reformation proved successful, as the Catholics regained old strongholds and energized their faithful among the Polish-speaking peasantry, while the Protestant ranks, centered among Germans and townspeople, diminished after 1573. Having defeated the Catholic Church bureaucracy, the Protestant gentry and nobles relaxed their efforts.[17]

The Elective Kings: Decline of the Polish State

At the time of the death of the childless Sigismund II, the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, powerful by virtue of its size, was already marked by internal weakness. Before the new king, Henry of Valois (r. 1573-1574; later Henry III of France), was chosen by the election Diet assembled in Warsaw, he had to consent to the so-called "Henrician Articles," or Pacta Conventa, which thereafter were to be sworn by each new monarch. The king's lost the prerogative to choose his successor; it was taken by the Sejm, composed of the nobility and the gentry. The king was also forbidden to declare war or increase taxes without the consent of the parliament. He was to be neutral in all religious matters and had to marry a wife selected for him by the Senate. A council of six senators was to remain constantly at his side to advise him. Should the king fail to observe any one of the articles, the nation was ipso facto absolved from its allegiance to him. Thus Poland changed its status from a limited monarchy to a parliamentary republic with a weak chief executive elected for life. The "Confederation of Warsaw" of 1573 was a successful attempt to guarantee internal religious peace religious toleration.

Reign of Stephen Báthory (1575-1586)

In a Europe of growing absolutism and in a country of long, open frontiers with aggressive neighbors ruled by centralized and militaristic governments, the Polish system harbored the seeds of disaster. Henry ruled only 13 months and then suddenly left to become king of France. The Senate and the Sejm failed to reach agreement on his replacement, and the gentry (szlachta) finally forced the election of the prince of Transylvania, Stephen Báthory (r. 1575-1586), giving him as his wife the last surviving princess of the Jagellonian dynasty. Báthory strengthened Polish dominion over Danzig, pushed Russia's Ivan the Terrible away from the Baltic, and regained Livonia, which Ivan had seized. Internally, he secured loyalty and aid from the Cossacks, runaway serfs who organized a sort of military republic on the large plains of the Ukraine, the "borderland" stretching from the southeast of Poland toward the Black Sea along the Dnieper River. Báthory augmented the privileges of the Jews, who were allowed a parliament of their own. He also reformed the judiciary, and in 1579 he founded the University of Wilno (Vilnius), which became the farthest outpost of Western European culture in eastern Europe.

Vasa dynasty (1587-1668)

Sigismund III Vasa (king of Poland 1587-1632; king of Sweden 1592-99))[18] was an ardent Catholic, determined to win the Swedish crown and bring Sweden back to Catholicism. Subsequently, Sigismund III involved Poland in unnecessary and unpopular wars with Sweden during which the Diet refused him money and soldiers and Sweden seized Livonia and Prussia. As the Russian czardom went through its "Time of Troubles," Poland failed to capitalize on the situation. In order to further Catholicism, the Uniate Church (acknowledging papal supremacy but following Eastern ritual and Slavonic liturgy) was created at the synod of Brest in 1596. The Uniates drew many followers away from the Orthodox Church in Poland's eastern territory. After prolonged war with Russia, Polish forces occupied Moscow in 1610. The office of czar, then vacant in Russia, was offered to Sigismund's son, Wiadysiaw. Sigismund, however, opposed his son's accession as czar. He hoped to obtain the Russian throne for himself. Two years later the Poles were driven out of Moscow and Poland lost an opportunity for a Polish-Russian union. There were two kinds of taxes, those levied by the crown and those levied by the state. The crown raised both customs duties and taxes on land, transportation, salt, lead, and silver. The state raised a land tax, a city tax, a tax on alcohol, and a poll tax on Jews. The exports and imports of the nobility were tax-free. The disorganized and increasingly decentralized nature of tax gathering and the numerous exceptions from taxation meant that neither the king nor the state had sufficient revenue to perform military or civilian functions. At one point the king secretly and illegally sold crown jewels. Sigismund's attempts to introduce absolutism, then becoming prevalent in the rest of Europe, and his goal of reacquiring the throne of Sweden for himself, resulted in a rebellion of the szlachta (gentry). In 1607 the Polish nobility threatened to suspend the agreements with their elected king but did not attempt his overthrow.

In 1618, the elector of Brandenburg became hereditary ruler of the duchy of Prussia. From then on, Poland's possessions on the shores of the Baltic were bordered on both sides by two provinces of the same German state.

Internal Disintegration and partition

During the reign of Sigismund's son Wiadysiaw IV (r. 1632-1648), the Cossacks in Ukraine revolted against Poland; wars with Russia and Turkey weakened the country; and the szlachta obtained new privileges, mainly exemption from income tax. Under Wiadysiaw's brother, John Casimir (r. 1648-1668), the Cossacks grew in power and at times were even able to defeat the Poles; the Swedes occupied much of Poland, including Warsaw, the capital; and the king, abandoned or betrayed by his subjects, had to seek temporary refuge in Silesia. As a result of the wars with Russia, Poland lost Kiev, Smolensk, and all the areas east of the Dnieper River by the Treaty of Andrusovo (1667). During John Casimir's reign, Prussia successfully renounced its formal status as a fief of Poland. Internally, the process of disintegration started. The nobles, making their own alliances with foreign powers, pursued independent policies; the rebellion of Prince Jerzy Lubomirski shook the throne; and the szlachta became blindly concerned with guarding its own "liberties." Beginning in 1652 the fatal practice of "liberum veto" was abused. This required unanimity in the Sejm and permitted even a single deputy not only to block any measure but to cause dissolution of the Sejm and submission of all measures already passed to the next Sejm. Thus foreign powers, using bribery or persuasion, routinely caused the dissolution of inconvenient sessions of the Sejm. Of the 37 Sejm in 1674-96, only 12 were able to enact any legislation. The others were dissolved by the "liberum veto" of one person or another. John Casimir, a broken, disillusioned man, abdicated the Polish throne in 1668 amid internal anarchy and strife.

By the 1700s, outside commentators routinely ridiculed on the chaos in the Polish legislature, blaming the liberum veto. [20] However Polish nobles regarded the veto as a constructive instrument to be used as a weapon against the aspirations of the monarchy to extend its power. The long-term result was a weak state that could not compete with its neighbors, and was partitioned among them, so that the nobles lost all their political rights as well as their nation state. During the 18th century intellectuals began to reconsider the role of the veto and the nature of Polish liberty, arguing that Poland had not been progressing as fast as the rest of Europe because of a lack of political stability. The exposure to Enlightenment ideas gave Poles further reason to reconsider other abstract concepts such as society and equality, and this led to discovery of the idea of the narod, or nation; a nation in which all people, not just the nobility, enjoyed the rights of political liberty.

Foreign Intervention: Prelude to Partition

Michael Korybut Wisniowiecki (r. 1669-1673) was a passive monarch who readily played into the hands of the Hapsburgs and lost Podolia to the Turks. His successor, the soldier John III Sobieski (r. 1674-1696), rescued Vienna from the Turks (1683) but had to cede territories to Russia in return for promised aid against the Crimean Tatars and Turks. After Sobieski's death, the Polish throne was occupied for seven decades by the German elector of Saxony, Augustus II (r. 1697-1733), and his son, Augustus III (r. 1734-1763). Augustus II virtually bought the election. In alliance with Peter the Great of Russia, he won back Podolia and western Ukraine, concluded the long series of Polish-Turkish wars by the Treaty of Karlowitz (1699), and tried unsuccessfully to regain the Baltic coast from Charles XII of Sweden. Augustus II was helpless when, in 1701, the elector of Brandenburg proclaimed himself sovereign "King in Prussia," as Frederick I and founded the aggressive, militaristic Prussian state, which eventually formed nucleus of a united Germany. Augustus was forced to cede the throne from 1704 to 1709, but regained it when Peter the Great of Russia defeated Charles XII at the battle of Poltava (1709). From this time until the partitions of Poland, the policy of Russia was to exercise political control over Poland in cooperation with Austria and Prussia. In 1733 the Poles, aided by the French, elected Stanislaw king for a second time, but Russian forces drove him out.

Last King of Poland

Augustus III (r. 1753-1763) was a puppet of Russia, and foreign armies criss-crossed the land. More enlightened Poles now realized that reforms were necessary. One faction, led by Prince Czartoryski, sought to abolish the fatal liberum veto, while the other, headed by the powerful Potocki family, opposed any limitation of their "liberties." Czartoryski's faction then entered into collaboration with the Russians, and in 1764 Catherine the Great, Empress of Russia, selected Stanislaw Poniatowski as king of Poland (r. 1764-1795). She selected Protestants for positions of power and used force and terror to get her way. As Stanislaw II, Poniatowski was the last king of Poland, reigning 1764-1795. Russia in 1767 forced the Diet to accept full religious toleration, political equality of dissidents, and confirmation of all ruinous "liberties," as demanded by the Russian-sponsored Confederation of Radom. This situation led in 1768 to the uprising of the Catholics, known as the "Confederation of Bar," crushed by Russia.

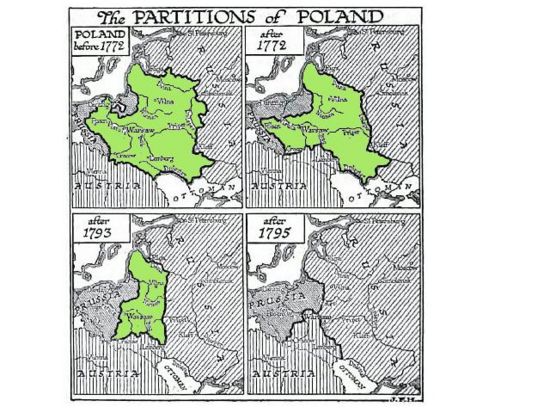

The First Partition

Poland, with a population of 11 million in 282,000 square miles, was internally paralyzed. It was still a union of the Kingdom of Poland and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, and their divergent interests prevented serious reforms. The elected monarchy was controlled by outsiders; the Sejm was paralyzed by the liberum veto. There was no central treasury anbd the army numbered a mere 12,000 soldiers. The weaknesses were promoted by Russia, with its expansionist plans; it bribed officials to keep the country weak.[21]

In the midst of the Russo-Turkish War of 1768-1774, the first partition of Poland was carried out by Prussia, Russia, and Austria.[22] Poland lost its part of Prussia (except Danzig and Torug) to Prussia; Red Russia, Galicia, western Podolia, and part of Kraków went to Austria; and eastern Byelarus and all other lands north of the Western Dvina and east of the Dnieper to Russia. The victors set up a new constitution for truncated Poland (which retained the liberum veto and the elective monarchy) and established a permanent council of 36 elected by the Diet.

The partition triggered a movement for reform and national revival. In 1773 the Jesuit Order was dissolved, and the Commission on National Education was created to reorganize the schools and colleges. The Great Sejm (1788-1792), led by the men of the Enlightenment Stanislaw Malachowski, Ignacy Potocki, and Hugo Kollontaj, adopted a new constitution in May 1791. What remained of Poland became a hereditary monarchy with ministerial responsibility and with a parliament elected every two years. The liberum veto was finally abolished; the towns obtained administrative and judicial autonomy as well as parliamentary representation; the peasants were placed under the protection of law; and measures aiming at the abolition of serfdom were sanctioned. A standing army was established. The reforms were possible because Russia was involved in a lengthy war against Sweden and because Turkey and Prussia concluded an alliance with Poland. But the reforms were too late. Internal Polish opponents formed the Confederation of Targowica, which the king joined; it obtained armed support from Russia.

Polish society comprised mostly rural peasants who were effectively serfs tied permanently to specific tracts of land. The nobles owned the land, but there was an unusually large number (over 150,000). Many nobles were poor and landless and attached themselves to wealthy nobles. All nobles were guaranteed legal equality, but none were allowed to engage in commerce. Business, crafts and the learned professions were handled by Germans and Jews, who dominated the towns and cities and had their own legal system, but lacked a political voice in a Poland controlled by nobles.[23]

Meanwhile some rich Poles (and Lithuanians) controlled vast estates in Polish-controlled Ukraine, and were a law unto themselves. Heavily taxed peasants were practically tied to the land as serfs Occasionally the landowners battled each other using armies of Ukrainian peasants. The Poles and Lithuanians were Roman Catholics and tried with some success to covert the Orthodox lesser nobility. In 1596 they set up the "Greek-Catholic" or Uniate Church, under the authority of the Pope but using Eastern rituals; it dominates western Ukraine to this day.

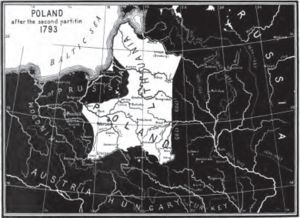

The Second and Third Partitions

Prussia soon ignored its peace alliance with Poland and together with Russia began the second partition in January 1793, taking more territory from the rump state. Prussia seized Danzig and Torug as well as Great Poland, while Russia took most of Lithuania and Byelarus and western Ukraine. The Poles fought back but were defeated by the Russians, and the small fragment that remained of Poland became a Russian puppet state. A vast national insurrection, which won over the peasantry by abolishing serfdom, was led in 1794 by Tadeusz Kosciuszko, but it eventually ended in failure. Subsequently, the third partition, in which Austria also joined, was carried out in October 1795, and the rest of Poland was divided up. Poland lost its independence and the nobles kept their lands but lost all political rights in the three countries that now controlled the Polish lands.

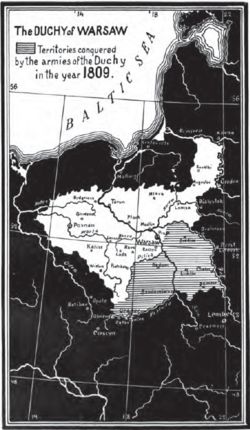

Although the Polish state ceased to exist, the Poles did not give up hope for the restoration of their independence. Each generation fought either by siding with the enemies of the partitioning powers or by rising in direct rebellion. As soon as Napoleon started his campaigns, Polish legions were formed in France. In 1807, after having defeated Prussia, Napoleon erected the Grand Duchy of Warsaw out of territory taken by Prussia, adding in 1809 the territories taken by Austria.

The Grand Duchy of Warsaw was a miniature Poland with an area of 64,000 square miles (166,000 sq km) and 4,350,000 inhabitants. It comprised about 30% of the Polish lands, including the heartland. Politically it was a French dependency, and it welcomed modern French ideas and legal codes. Poles celebrated what they thought was the beginning of their total liberation. The price was service in Napoleon's wars; 96,000 marched behind him to Moscow in 1812; 28,000 returned.[24]

Russian-Dominated Areas

After Napoleon's defeat, the Congress of Vienna (1815) confirmed the partitions with the following changes: Kraków (Cracow) became a small free city-- a republic under the protection of the three partitioning powers (1815-1848); the western part of the Grand Duchy of Warsaw was returned to Prussia and made the Grand Duchy of Poznan (1815-1846); the other part was declared a monarchy (so-called Congress Poland) and united with Russia in a personal union, with the czar serving as its constitutional king and the Polish elite enjoying a favorable status. Indeed, Congress Poland was the freest part of the Russian Empire, for a while.

In November 1830 junior officers inspired by the Romantic movement, which glorified the ethnic nation and its language, rose against Russia. They had an army of 80,000 and limited popular support; the rebels won some battles but lacked international support (even the Pope was hostile) and were crushed. Czar Nicholas I disbanded the Polish parliament and army, and began retaliatory measures against schools and universities. Ten thousand political and intellectual leaderswent in exile; a vibrant Romantic Polish culture flourished in Paris, led by poet Adam Mickiewiz (1798-1855) and composer Fryderyck Chopin (1810-48). In 1846 and 1848 came new revolts, which were crushed in turn. In 1863 another national uprising against Russia broke out, and after two years of mostly guerrilla warfare the Poles again were defeated. Subsequently, the autonomy of Congress Poland was abolished, the area was incorporated into Russia, and Russification of Polish society intensified. Yiddish-spealing Jews comprised about 15% of the population, concentrated in the cities; they had a second-class legal status and no political voice. In Warsaw, 30% of the people were Jews, most concentrated in poverty-stricken ghettoes with a distinctive dress and lifestyle. Their merchants monopolized some trades such as grain, lumber and banking. They and the rural Poles emigrated in large numbers to the United States, 1900-1914.

Poland's political situation improved somewhat after Russia's defeat by Japan in the Russo-Japanese War of 1904-1905. Polish deputies sat in all four Russian dumas (1905-1917), working for autonomy and the liberalization of the Russian government.

Prussian-Controlled Areas

In the Prussian-dominated area, the Germanization of the former Polish territories was enforced. The farms of Polish peasants were expropriated, German colonization of the Polish areas was sponsored by the administration, and Polish schools were closed. In spite of these efforts, however, at the end of the 19th century the Poles still represented a strong, organized national group. Many Poles migrated to Germany to work in the coal mines, while even larger numbers went to the United States, as did many Jews.

Austrian controlled Areas

In the Austrian territories the situation was better. After 1866 Galicia obtained administrative home rule; schools, offices, and courts used the Polish language. The universities of Kraków (Cracow) and Lwów (renamed Lemberg) became cultural centers for all Poles. By 1900 new Polish political parties had emerged (the National Democratic, the Polish Socialist, and the Peasant parties). In all three parts of Poland, members of the middle class, workers, and peasants participated increasingly in resurgent national life. Romanticism prevailed so that the preservation of the Polish language and culture became a crucial battle. It was led by the intellectuals, especially poets and authors, and by the lower clergy of the Catholic Church. In all areas heavy emigration of Poles and Jews to the United States continued, especially between 1900 and 1914.

World War I

World War I broke the solidarity of the partitioning powers, with Russia at war with Germany and Austria. To gain Polish support wach belligerant offered concessions to the Poles. The Poles had to fight in opposing camps and their land became a main battlefield of the Eastern Front.[26] Sharp differences among political groups emerged. The conservative National Democrats, led by Roman Dmowski (1864-1939), regarded Germany as the main enemy and promoted the victory of the Allies. Their goal was the union of all Polish territories under Russian rule with autonomous status. The radical elements, led by the Polish Socialist Party, viewed Russia's defeat as a vital condition for Poland's independence. They believed that the Poles should organize their own military forces. Several years before World War I broke out Józef Pilsudski (1867-1935), a principal leader of this group, started to train Polish youth in Galicia. During the war, he formed the Polish legions and for some time fought at the side of Austria.

The Polish cause became an international issue. Early in the war the Russians promised to unite the three parts of Poland as an autonomous state within the Russian Empire. In the autumn of 1915 most of Russian Poland fell into the hands of Germany and Austria. In November 1916 the Central Powers proclaimed the formation of the Kingdom of Poland under the protection of the Austrian and German emperors. The chief motive of the proclamation was political (to create a buffer Polish state, which would be an integral part of the German-planned Mitteleuropa), not military (to make use of the large reservoir of Polish manpower). Pilsudski, in response to the proclamation, decided to cooperate with the Central Powers because of his desire to form a separate Polish army and government, both of which were necessary for the creation of an independent Poland.

After the March 1917 liberal revolution overthrew the czar in Russia, the new provisional government sought independence and international recognition. By then the popularity of the Polish cause was strong in the West. IN January 1917, American President Woodrow Wilson spoke for a united, independent Poland. In France the Polish National Committee led by Dmowski and Ignace Jan Paderewski was elected, and the Polish army was formed with Józef Haller as its commander-in-chief. Late in 1917 the Polish National Committee was recognized by the Allies as the official representative of the Poles. In mid 1917, the Central Powers interned Pilsudski and disbanded his legions for refusal to swear allegiance to them. The Central Powers, however, agreed to the formation of the Polish Regency Council. On Jan. 8, 1918, President Wilson in his Fourteen Points demanded an independent Poland with free access to the sea. In June, 1918, the Allies officially recognized Poland as an Allied belligerent. On October 6, while the Central Powers were crumbling, the Regency Council in Poland announced the formation of an independent government. Pilsudski was released from his internment, and on November 10 he arrived in Warsaw. The next day the Regency Council appointed him the supreme commander of all Polish forces and on November 14 resigned in his favor. By then Germany had surrendered, the Austro-Humgarian Empire had disintegrated, and Russia was in the throes of a revolutionary civil war.

Independence (1918-1939)

Poland was now a free country covering 150,000 square miles and including 27 million inhabitants. Two-third of these were Poles but there were significant minorities, including 4 million Ukrainians, 3 million Jews and 1 million Germans. War damage had been severe; prosperity was elusive and the economic system was not integrated, having developed under three very different empires. Poland had no currency or civil service of its own; and, above all, its frontiers were not defined. The Prussian part was still under German rule in 1918; the Bolsheviks were threatening from the east; and the frontiers with Lithuania and Czechoslovakia were disputed. The pace of reconstruction and rehabilitation was fast, however. After a transitional period with a socialist cabinet, Paderewski was appointed prime minister on Jan. 17, 1919, and Dmowski was named to head the Polish delegation at the Versailles Peace Conference. National elections were in January 1919 and the new Sejm (parliament) confirmed Pilsudski (1867-1935) as head of state. The American Relief Administration, led by Herbert Hoover, supplied great quantities of clothing, food, and medicines, thus probably saving hundreds of thousands from famine and epidemic. On Mar. 17, 1921, a democratic constitution was adopted. By January 1920, an army of 600,000 was under Pilsudski's command. Pilsudski fought six border wars in three years, largely against the new Bolshevik regime in Russia, before the Treaty of Riga in 1921 established secure eastern borders. Pilsudski's key victory was the battle for Warsaw: in August 1920, in the celebrated "miracle on the Vistula," his forces routed five Russian armies.

In 1919 the Polish forces under Pilsudski took Galicia, Volhynia and parts of Lithuania and Belorussia from the Russians. Pilsudski then proposed an attack on Ukraine in order to establish Poland as a significant player in European affairs. In preparation agreements signed between Poland and leaders of the Soviet White army, including General Anton Denikin, in which the Whites promised to respect Poland's territorial claims in case of victory. Meanwhile Bolshevik leaders, who were looking for allies, turned to Germany. This alliance threatened Poland with being caught in a helpless position between two powerful entities. Pilsudski thought of a Poland in the Jagellonian concept of a federation of Poles, Lithuanians, and Ukrainians. On Apr. 22, 1920, he concluded an agreement with the Ukrainian leader Simon Petliura and launched an offensive for the conquest of Ukraine from the Bolsheviks. On May 7, the Poles occupied Kiev but by June 8, pressed by the Bolshevik forces, they started a withdrawal. By the end of July, the Bolsheviks were approaching Warsaw; the Poles stood alone. But a Polish victory at the gates of Warsaw (Aug. 15, 1920) ended the war. The subsequent Treaty of Riga (Mar. 18, 1921) represented a territorial compromise for both sides and closed off Pilsudski's territorial aspirations, curtailed Bolshevik geopolitical goals, and left Poland as a barrier between Germany and Russia, as opposed to being a bridge between the two. Thus in the east the Polish-Soviet frontiers were settled by the Poles and the Bolsheviks themselves after two years of warfare called the "Russo-Polish war."

Poland's western frontiers were delineated by the Allies at the Versailles Conference, which assigned Poland part of Pomerania and access to the sea, declared Gdansk (Danzig) a free city in which Poland had special rights, and ordered plebiscites in East Prussia (1920) (voting for Germany) and Silesia (1921) (voting mostly for Germany but parts given by the League to Poland). In the south, Teschen was divided between Poland and Czechoslovakia, leaving approximately 140,000 Poles outside Poland, a fact strongly resented by the Poles. The bitter disputes between Poland and Lithuania over Wilno (Vilnius), ethnically Polish but historically Lithuanian, resulted in Polish occupation on Oct. 9, 1920, which was confirmed on Feb. 10, 1922, by the democratically elected regional assembly. Lithuania protested, but the Lithianians there were expelled and Wilno became part of Poland until 1939, when Societs and Germans took over. In 1944 the Poles were expelled and Vilnius became the capital of Lithuania.

Instability and dictatorship

Wladyslaw Sikorski (1881-1943), as head of the Polish general staff from 1921 encouraged a Polish alliance with France and developed the military and political doctrine of the "two enemies," which defined Polish policy. Elected prime minister in 1922, he tried to secure international recognition of Poland's eastern borders. Disagreement with Pilsudski over military issues forced him to resign in 1925.

During the years 1919-1926, political, social, and economic instability was endemic. There were ten cabinets, with an average duration of no more than six months. The Sejm was highly fragmented, with a multitude of parties and programs. The ever-changing coalition governments were unstable, and the executive was generally weak. There were tensions with national minorities, which constituted one third of the population. The economy was plagued by uncontrolled inflation; in 1923 there were 15 million Polish marks to the U.S. dollar, compared to nine in 1918. Unemployment in the cities was high. On the international scene, Germany made territorial demands in violation of the Locarno treaty. In May 1926, Pilsudski carried out a military coup, overthrowing a democratically elected government.[27] He wanted to replace it with a coalition of representatives of all political sides; for that reason he created the Non-Party Bloc for Cooperation with the Government, which became the strongest party in the Sejm by the 1928 elections. This party was made up primarily of his legionnaires, so the government was under Pilsudski's control. He had Ignacy Moscicki elected president.[28]

Until Moscicki's death in May 1935, Pilsudski directly or indirectly held the reins of power in a unique personal dictatorship. He set up the "Sanacja," a purification regeneration movement. Pilsudski exercised power mostly through his supporters, not personally, trusted the military exclusively, and despised society at large. Ironically the very politician who had helped to create a democratic Poland started to pull down what he believed to be a faulty political system by trying to minimize the role of parliament to a minimum.

The regime became increasingly authoritarian. The Fascist ("the Falanga") and Communist parties were outlawed, and political trials resulting in long prison sentences were commonplace. Anti-Semitic restrictions were introduced, despite Pilsudski's previous support for Jews. In spring 1935, a new constitution was voted that greatly increased the power of the president, curtailed the rights of the political parties, and limited the powers of the parliament. The new constitution did not gain the approval of the main political parties, and the strife between them and Pilsudski's regime continued. Pilsudski made the administration more efficient, and improved the morale of the army, while being unable to afford new equipment. Inflation was brought under control, the zloty (introduced in 1924) became a stable currency. The worldwide Great Depression hit Poland hard, as Warsaw raised taxes and cut government expenditure. By 1939, Poland's per capita output was 15% below that of 1913.

Foreign Policy

With Russia and Germany threatening, the cornerstones of Poland's foreign policy were the alliances concluded with France and Romania in 1921, as well as support of the League of Nations. In 1932, a nonaggression pact was concluded with the Soviet Union and . Colonel Józef Beck became Poland's foreign minister.

After Adolf Hitler's takeover of Germany in January 1933, Beck, on Pilsudski's instructions, suggested to France a preventive action against Nazi Germany. The response was negative and Britain and France entered into a Four-Power Pact with Germany and Italy, a step viewed as unfriendly in Poland and the countries of the Little Entente (Czechoslovakia, Yugoslavia, and Romania). Subsequently, Poland pursued a policy of strict neutrality between its two mutually hostile neighbors, Germany and the Soviet Union. On Jan. 26, 1934, a ten-year nonaggression pact was concluded with Germany, and soon afterward the nonaggression pact with the Soviet Union was expanded. In March 1936, at the time of the German military occupation of the Rhineland, Beck declared to the French and Belgian governments that Poland would support them if they opposed Germany. The declaration had no effect, and afterward the growing power of Germany kept Poland in check. In October 1938, following the Munich Agreement on dismemberment of Czechoslovakia, Poland occupied the Teschen district, an action that provoked criticism in many circles. In March 1939, Hitler presented his demands on Poland. On March 31 Britain guaranteed Polish territorial integrity, and Franco-British-Soviet negotiations, aimed at checking Germany's expansions, started in Moscow. The Soviet Union secretly demanded the right to occupy eastern Poland and simultaneously entered into secret negotiations with the Nazis. On Aug. 23, 1939, the sensational and unexpected Nazi-Soviet pact of nonaggression was concluded, the secret clauses of which provided for the partition of Poland between Germany and Russia. Having secured Soviet neutrality, Hitler felt free to attack Poland on Sept. 1, 1939, thus starting World War II.

World War II

The Poles, unaided militarily by either France or Britain (both of which declared war on Germany on Sept. 3, 1939), were unable to withstand the surprise attack of Germany's motorized armies and powerful air force. The situation became hopeless when, on September 17, Soviet troops attacked Poland from the east. Subsequently, the Polish government and the remnants of the armed forces passed into Romania, where they were interned. Before crossing the frontier, President Moscicki, in accordance with the constitution, resigned from his post in favor of Wladyslaw Raczkiewicz, the former president of the Senate. The latter, then in Paris, appointed General Wladyslaw Sikorski as premier, and the new government won prompt recognition by all countries except the Axis powers and the Soviet Union.

The new Polish army, navy, and air force, totaling 80,000 men, were formed in France. The Poles fought at the side of France until June 1940; then the Polish government went to Great Britain and there formed a new army, which eventually fought in Norway, North Africa, Italy, France, Belgium, and the Netherlands. In the Battle of Britain in 1940, Polish airmen were responsible for more than 15 percent of the German air losses. Altogether, more than 300,000 Poles served abroad in the Allied armed forces. Polish logicians had broken the German's top secret "enigma" code, and brought it to Britain, giving the Allies an enormous intelligence advantage during the war.[29]

German Occupation

The German occupation of Poland was exceptional in its cruelty. Hitler incorporated parts of Poland into the Third Reich and transformed the remaining occupied areas into a General-Gouvernement under a German governor. All industrial and agricultural production was subordinated to German military needs. Polish high schools and universities were closed, and intellectuals were harassed and persecuted. On the first day of the 1939 academic year at the Jagellonian University in Cracow about 180 professors and assistants were arrested and deported to concentration camps at Sachsenhausen, Oranienburg, and Dachau. The collections and libraries of 136 university institutes were destroyed. robbed, evacuated to Germany, or taken over by various German institutes.

Hundreds of thousands of people were sent to factories in Germany as slave laborers, or sent to concentration camps. Special savagery was reserved for the Jews. Polish Jews were initially confined in a few large closed ghettos and were forbidden to live or to work (without a special permit) outside them. Indiscriminate mass murders of Jews began immediately. When the "Final Solution" or "Holocaust" was implemented in 1942, the Polish Jews were deported to death camps, where some three million of them were murdered. The largest and most notorious of the Nazi death camps in Poland was near Auschwitz.

The Polish people opposed the Nazi occupiers through widespread resistance, both civilian (for example, setting up an underground Polish society complete with schools and universities) and military. The military resistance was led mainly by the Home Army, which became the largest resistance movement in Nazi-occupied Europe.[30]

Polish-Soviet Agreement of 1941

After Germany attacked the Soviet Union in June 1941, the Polish government-in-exile, under strong British pressure, concluded a pact with the Soviet Union on July 30, 1941. According to this pact, diplomatic relations between Poland and the U.S.S.R. were to be restored; the Nazi-Soviet agreement concerning the partition of Poland was declared null and void; all Polish war prisoners and deportees were to be released; and an autonomous Polish army was to be formed in the Soviet Union. The Soviet government did not live up to the agreement, however. It refused to recognize the prewar Polish-Soviet boundary and released only a fraction of the Poles being held in the U.S.S.R.

In April-May 1940 about 15,000 Polish prisoners of war held by the Soviets were shot on orders from Stalin; Polish protests led Stalin in April 1943 to break diplomatic relations with the Polish government-in-exile.[31] General Sikorski was killed in an air accident (July 4, 1943), and his successor, Stanislaw Mikolajczyk, sought in vain to reestablish diplomatic relations with the Soviet Union. Subsequently, the Soviet authorities organized the nucleus of the future Polish Communist government and army in the Soviet Union. In November-December 1943, at the Tehran Conference President Franklin D. Roosevelt and Prime Minister Winston Churchill secretly agreed with Stalin that the Curzon Line, roughly corresponding to the boundary agreed upon by the German and Soviet governments in 1939, should in the future become Poland's eastern frontier.

Jews in Warsaw Ghetto: 1943

During the German occupation there were two distinct uprisings in Warsaw, one in 1943, the other in 1944. The first took place in an entity, less than two square miles in area, which the Germans carved out of the city and called "Ghetto Warschau." Into the thus created Ghetto, around which they built high walls, the Germans crowded 550,000 Polish Jews, many from the Polish provinces. At first, people were able to go in and out of the Ghetto, but soon the Ghetto's border became an "iron curtain." Unless on official business, Jews could not leave it, and non-Jews, including Germans, could not enter. Entry points were guarded by German soldiers. Because of extreme conditions and hunger, mortality in the Ghetto was high. Additionally, in 1942 the Germans moved 400,000 to Treblinka where they were gassed on arrival. When, on April 19, 1943, the Ghetto Uprising commenced. The armed uprising was led by the Jewish Fighting Organization (ZOB). After a month of desperate fighting, with no outside aid, the uprising was crushed. The Germans systematically razed the entire ghetto and deported the 60,000 survivors to the Treblinka death camp.[32]

Warsaw Uprising of 1944

The uprising by Poles began on August 1, 1944 when the Polish underground, the "Home Army," aware that the Soviet Army had reached the eastern bank of the Vistula, sought to liberate Warsaw much as the French resistance had liberated Paris a few weeks earlier. They had not coordinated their plans with the Allies. Stalin had his own group of Communist leaders for the new Poland and did not want the Home Army or its leaders (based in London) to control Warsaw. So he halted the Soviet offensive and gave the Germans free reign to suppress it. During the ensuing 63 days, 250,000 Poles fought; with only limited outside help (from U.S. air drops), they were overwhelmed. Finally the Home Army surrendered to the Germans who forced survivors to leave the city, then destroyed 98% of the buildings in Warsaw.[33]

The Lublin Government

In January 1944 the Soviet Army crossed Poland's prewar eastern frontier in pursuit of the retreating German armies, and on July 22 the Soviet-sponsored Polish Committee of National Liberation established itself in Lublin. On Aug. 1, 1944, Polish underground forces in Warsaw led by General Tadeusz Komorowski started an uprising against the Germans. Then the Soviet Army, at that time already in the suburbs of Warsaw, stopped its offensive. After 62 days of desperate fighting, the Germans crushed the unaided uprising and almost totally destroyed Warsaw. On Jan. 5, 1945, Moscow reorganized the Lublin Committee as the provisional government of Poland.

At the Yalta Conference (Feb. 4-11, 1945) Churchill and Roosevelt formally recognized the incorporation into the Soviet Union, of the eastern part of Poland, inhabited primarily by Ukrainians and White Russians, not Poles. They agreed with Stalin that Poland should be compensated by German territory in the west. The three wartime allies agreed, moreover, that the (Communist) Lublin government should be enlarged by the addition of non-Communist members from within and outside Poland and that free elections were to be held within Poland. Subsequently, Mikolajczyk, who, on Nov. 7, 1944, resigned his post as the premier of the government-in-exile, and a few others joined the Lublin government, which, on July 5, 1945, was formally recognized by Great Britain and the United States as Poland's Provisional Government of National Unity. On the same day, recognition was withdrawn from the government-in-exile, headed at that time by a veteran Socialist leader, Tomasz Arciszewski. In August at the Potsdam Conference, it was agreed that southern East Prussia and the territories up to the Oder and Neisse rivers would be placed under Polish administration. The Soviet Union was also to give Poland 15% of its $10 billion reparation claim to be collected from Germany.

Poland and the Cold War

Stalin's decision to take control of Poland and the rest of Eastern Europe was the single most important immediate cause of the Cold War with the United States and western Europe. Historians continue to debate whether Stalin's move reflected the traditional czarist goal of controlling the Slavic lands (especially since much of Poland had been controlled by Russia before 1918), or whether his main goal was to stop the spread of capitalism and speed up the conversion of Europe to Communism. He believed that capitalism was dying. Stalin, a total dictator, never explained his policies to his subordinates; he did say that he wanted a buffer between the Soviet Union and Germany. But Germany in 1945-47 was weak and split four ways; he perhaps meant a buffer between the Soviet Union and an American dominated Europe. Simple arithmentic showed that the Soviet population base with the addition of the population of Poland (and the other satellites) would outnumber the West. Indeed for 40 years NATO wrestled with the problem of stopping an invasion based on the numerical superiority of the Warsaw Pact armies.[34]

Communist Poland

With the Soviet Army in full control in Poland, and the government-in-exile watching helplessly in London, Stalin turned over power to the Polish Communists he had selected. The Soviets arrested and executed non-Communist leaders of the former Polish underground. Mikolajczyk, who had returned to Poland, and the members of his Polish Peasants' Party were persecuted. The Communists gradually seized control of the Polish army, police, media, and transportation network. A new security force numbering 200,000 operatives planted spies everywhere; 5000 political opponents were executed and tens of thousands imprisoned.[35]

The Communist party retained the system of elections but took control of the parties. At the first postwar elections in January, 1947, The Communists took 382 and the Polish Peasants' Party 28 (out of 444). Stalinist Boleslaw Bierut became president and the process of Stalinization was speeded up, with mass arrests, deportations to the Soviet Union, and persecution of church leaders, intellectuals, and members of the non-Communist World War II underground. In October, Mikolajczyk and a few other Peasant leaders fled to the West. In September 1948 Wladyslaw Gomulka, the general secretary of the (Communist) Polish Workers' Party and deputy premier, was accused of "rightist and nationalist deviation" (i.e., insufficient subordination to the Soviet Union) and forced to resign both posts; surprisingly he was not executed, but survived to make a comeback. The Roman Catholic Church suffered persecution, culminating in the arrest of the primate of Poland, Stefan Cardinal Wyszynski, in September 1953. In December 1948 the Polish Workers' Party merged with the already purged Polish Socialist Party and became the Polish United Workers' Party (PZPR). Moscow forced Poland to renounce the American offers of financial aid through the Marshall Plan. In 1949 the Polish Peasants' Party was fused with the Communist-controlled peasant groups under the name of the United Peasants' Party, and Konstantin Rokossovsky, a Russian general, became Poland's minister of national defense and commander-in-chief. He was close to Stalin. On June 7, 1950, a Polish-East German agreement recognized the Oder-Neisse line as the permanent western frontier. Communists for years warned that West Germany would eventually demand return of lost areas unless Poland stood with the Soviets.[36]

In 1955 Poland joined the Soviet-sponsored Warsaw Pact military alliance, which interlaced its military with the Soviet Union. Bolesław Bierut (1892-1956), head of the Polish Workers Party, served as president 1947 to 1952, then abolished the presidency and became premier. In 1954 Bierut resigned the premiership in favor of Józef Cyrankiewicz (1911-89) but Bierut remained in the more powerful role of the head of the PZPR until his death in 1956.

From 1944 to 1970 anti-Semitism was an instrument of political struggle within the ruling Communist Party, the absence of a large Jewish population being irrelevant. Anti-Semitism was associated particularly with the nationalist line of Gomulka and his allies.

Economy

The successful rebuilding after World War II of the nearly totally destroyed economy was followed by promotion of the Stalinist economic system. Its promoters claimed that it was necessary to accelerate economic growth and build a modern industrial base, though Poland lagged far behind western Europe in industrialization. In 1949 Poland joined the Soviet-dominated Council for Mutual Economic Assistance (COMECON). The effect was to interlock the Policsh economy with the economically backward Russian economy, and impede long-term growth. However, as farmers moved to more efficient factory jobs the economy did grow. The Soviet-type system was unable to collect or process accurate information centrally--prices did not reflect costs but were political devices negotiated by power brokers inside the Communist party. Centralization was inefficient, necessitating reform moves by Gomulka after 1956. These reforms were cautious, partial, and revocable and a recentralization of the economy took place during the 1960s.[37]

After 1945 modernization was accompanied by demands for more meat instead of bread by workers and farmers. The new demands on meat production could not be met because of the government's policy of investing in factories, not farms. People began meauring the performance of the government by the availability of meat; its performance was poor. Fearing mass protests, the Commuist party did not balance the market by raising prices but instead spent its money on subsidies to keep food prices low. Every attempt to raise prices caused grumbling; twice (1970, 1976) the government had to recerse the increases. By 1980 the scale of the imbalance of supply and demand led to meat rationing, a system that broke down in 1989, when in view of roundtable talks and rumors about anticipated price increases, the farmers simply ceased selling meat. The final solution was introducing market prices in the summer of 1989. The chronic imbalance of supply and demand can be related to the coexistence of a system of trading and distributing food products that from 1948 was state-owned and subjected to the directives of the Communist ideologues, while the agricultural sector comprising private farms that reacted to market stimuli.[38]

Gomulka era: 1956-1970

In June 1956 some 50,000 workers and students demonstrated in Poznan against Soviet domination. Spreading discontent fuelled by Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev's denunciation of Stalin and by the Hungarian revolution, led to changes in the Communist leadership. Wladyslaw Gomulka (1905-1982), isolated since 1948, was rehabilitated and elected general secretary of the PZPR in October 1956. He denounced the Stalinist terror and abuses by the party, revealed mismanagement in the economic field, forced the principal spokesmen of the Stalinist era to resign, removed Rokossovsky and other Russians from control of the Polish armed forces, and obtained a measure of independence from the Soviet Union. The United States, with President Dwight D. Eisenhower eager to provide support for more independence from Moscow, gave wheat and farm equipment amounting to $588 million. In addition Poland was granted most favored nation trading status. The policy was continued without major changes into the 1960s.

After 1956, most collective farms were dissolved and the land was returned to individual farmers; limited private initiative reappeared in trade and industry; the press became freer; workers obtained a greater voice in factory management; and the government put more emphasis on the production and distribution of consumer goods. Relations with the Catholic Church also improved temporarily. Although Poland still supported the Soviet Union on international issues, economic aid from the United States helped it be a little more independent.[39]

Gomulka, who remained in power 1956 to 1970, remained subject to conflicting pressures--a growing popular demand for more freedom and a strong resistance to liberalization from the Stalinist wing of the party. During the 1960s the pressures on Gomulka intensified. A reform of the courts had been carried out in 1962, and compulsory courses in Marxism-Leninism had been dropped from secondary schools and universities. However, the government also sought to restore tight discipline by increasing pressure on the peasants to join the agricultural circles, by continuing its anti-Church measures, and by maintaining restrictions on artistic and intellectual freedom. In March 1968 these restrictions provoked widespread student demonstrations, which demanded greater freedom of speech and of the press and a relaxation of censorship. The government responded by firing protestors from their jobs, arresting students and intellectuals, and launching a massive "anti-Zionist" and "anti-revisionist" campaign, They forced most of the remaining Polish Jews and many intellectuals to emigrate. Poland opposed Czechoslovakia's democratic reforms during 1968 and took part in the invasion of that country by the Soviet Union and Warsaw Pact in August 1968.

In December 1970 the Gomulka regime announced price rises for food and other basic commodities and introduced a new system of wage payments based on factory efficiency. Workers reacted violently. Riots, centered around the port cities of Gdansk, Gdynia, and Szczecin, were crushed by the army, leaving at least 70 workers dead and more than 1,000 injured. Gomulka was forced to resign as Communist party chief and was replaced by Edward Gierek.

The Gierek Regime

Gierek retreated by abandoning the food price increases and the incentive wage system. He introduced a new five-year plan that put more emphasis on housing and consumer goods. Peasants were mollified by the abolition of compulsory delivery of agricultural produce to the state and relations were normalized with the Church. Gierek launched a long-term program of industrial expansion, which was financed largely by loans from the West.[40]

By the mid-1970s, however, meeting the payments on these Western loans was extremely burdensome. In 1976, therefore, the government sought to increase export earnings by cutting back on food subsidies. But strikes and demonstrations again made the government back down. After a new wave of violent protest due to the deterioration of wages and standards of living, Gierek tried and failed to hit two targets at the same time: to increase the standard of living of the population and modernize industry.

Indignation over mass arrests and harassment of the strikers and their families led to the formation of the Committee for the Defense of Workers (KOR), composed of some of Poland's best-known oppositionists and intellectuals. In 1978, KOR transformed itself into the Committee for Social Self-defense (KSS), thus becoming the first nucleus of an organized opposition in Poland.

Still another attempt to raise food prices, in July 1980, led to the greatest upheaval of all. Hundreds of thousands of workers went on strike, first in the Baltic cities of Gdansk, Gdynia, and Szczecin and then in Silesia and other areas. The workers set up strike committees headed by an inter-factory strike committee. The inter-factory committee, led by Lech Walesa (1943- ), advanced a list of 22 economic and political demands, including not only higher wages and cheap food but also the right to form independent trade unions, the right to strike, and a loosening of censorship. They avoided any challenge to Communist political supremacy or the Warsaw Pact. The government negotiated with the workers and eventually agreed to most of their demands, including the right to strike and the right to form independent unions. Gierek was forced to resign and was succeeded as party chief by Stanislaw Kania.

In 1987, a more radical reform movement started again which had three major components: reorganization of the central economic bureaucracy and limitation of its formal and informal powers; an opening of new possibilities for individual entrepreneurship, including joint ventures with foreign capital; and an increase of the role of monetary categories.

Solidarity in opposition

With the right to independent trade unionism affirmed, workers flocked from the old government-controlled unions into a new independent union federation, Solidarity, which soon had 10 million members. Pressed by rank-and-file militants, Solidarity fast became a source of political as well as economic demands. The Solidarity demands were increasingly bold, and strikes were frequent, though the union's top leaders, headed by Lech Walesa, and the Church tried to discourage actions that might provoke the Soviet Union to intervene in Poland.

Thus the crisis intensified. Meanwhile, agricultural and industrial production, already inadequate, became more so during 1981, and food shortages became commonplace. The PZPR took steps to democratize itself at an extraordinary congress in July 1981, but the conflict between the regime and Solidarity heightened nonetheless. Solidarity demanded that workers be given the right to manage the enterprises in which they worked. The party refused, jealous of its power to appoint all managers. In September, at its national congress, Solidarity issued a startling appeal to all the workers of Eastern Europe to form free trade unions. The congress was followed by a fresh wave of strikes, along with mounting food shortages. The police repressed some dissidents and union militants, but the party's confidence in Kania's ability to restore order and production waned, and on October 18 he was replaced by General Wojciech Jaruzelski, the commander of the Polish armed forces.

Martial Law

In December Solidarity called for a referendum on Communist rule and on Poland's ties to the Soviet Union. In response, on December 13, Jaruzelski imposed martial law, supplanting civilian authorities with a military council of national salvation and arresting the major Solidarity leaders and other opponents. Strikes and sit-ins erupted across the country in factories, mines, shipyards, and universities; the police broke them up. The government stated that it did not intend to revoke the reforms instituted in 1980, but, when Solidarity leaders refused to compromise, it enacted a new labor law in October 1982 abolishing Solidarity and providing for its replacement by smaller, government-controlled unions. Over the following months it released most of the detainees, and in July 1983, after a visit to Poland by Pope John Paul II, it officially ended martial law. Strong pressure from the Solidarity underground, the Vatican, the United States and international public opinion forced Jaruzelski to proclaim an amnesty in 1984. The crisis, however, was not resolved. Although the paralyzing strikes had been put down and the threat to Communist rule contained, support for Solidarity remained widespread.