New Deal: Difference between revisions

imported>Nick Gardner No edit summary |

imported>Nick Gardner |

||

| Line 7: | Line 7: | ||

==Relief, Recovery, and Reform== | ==Relief, Recovery, and Reform== | ||

The New Deal had three components: | The New Deal had three components: relief, recovery, and reform - ''The Three RS''. | ||

''Relief'' was the | The ''Relief'' component was intended to put the unemployed to work and help those hardest hit by the depression. It expanded the previous administration's work relief program, and added an extensive further sequence of employment-generating schemes, followed by the introduction of a number of social security and unemployment insurance systems. | ||

'' | The ''Recovery'' component was intended to return the country to prosperity by direct government intervention in its economy. It included programmes of financial assistance to banks and mortgage-lenders, subsidies to farms and busineses, the encouragement of trade union membership, and the maintenace of wage levels. | ||

The ''Reform'' component included the creation of the ''Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation'', which had the immediate purpose of restoring confidence in the country's banks and the longer term purpose of regulating their conduct; and the setting up of the ''Securites and Exchange Commission'' to regulsate other parts of it financial system. | |||

By 1934, the Supreme Court began declaring significant parts of the New Deal unconstitutional. The programs were quickly fixed to pass muster, but in 1937 Roosevelt stunned the nation by a surpise proposal to pack the Supreme Court by adding five new justices. The proposal failed and Roosevelt permanently alienated many conservative Democrats; however the Supreme Court started upholding New Deal laws. Justices then started retiring, allowing Roosevelt to selected a majority of the Court. By 1942, the Supreme Court had almost completely abandoned its "judicial activism" of striking down congressional laws. The Supreme Court ruled in ''[[Wickard v. Filburn]]'' that the [[Commerce Clause]] covered almost all such regulation allowing the necessary expansion of federal power to make the New Deal "constitutional". | By 1934, the Supreme Court began declaring significant parts of the New Deal unconstitutional. The programs were quickly fixed to pass muster, but in 1937 Roosevelt stunned the nation by a surpise proposal to pack the Supreme Court by adding five new justices. The proposal failed and Roosevelt permanently alienated many conservative Democrats; however the Supreme Court started upholding New Deal laws. Justices then started retiring, allowing Roosevelt to selected a majority of the Court. By 1942, the Supreme Court had almost completely abandoned its "judicial activism" of striking down congressional laws. The Supreme Court ruled in ''[[Wickard v. Filburn]]'' that the [[Commerce Clause]] covered almost all such regulation allowing the necessary expansion of federal power to make the New Deal "constitutional". | ||

Revision as of 07:43, 6 February 2009

The New Deal was a programme of Congressional enactments and Presidential orders that was introduced in the United States during the 1933–1938 period for the purpose of providing for the relief, recovery and reform of its economy in response to the events of the Great Depression

- (For an annotated list of New Deal measures see the addendum subpage)

- (For the sequence of New Deal legislative measures see the timelines subpage)

Relief, Recovery, and Reform

The New Deal had three components: relief, recovery, and reform - The Three RS.

The Relief component was intended to put the unemployed to work and help those hardest hit by the depression. It expanded the previous administration's work relief program, and added an extensive further sequence of employment-generating schemes, followed by the introduction of a number of social security and unemployment insurance systems.

The Recovery component was intended to return the country to prosperity by direct government intervention in its economy. It included programmes of financial assistance to banks and mortgage-lenders, subsidies to farms and busineses, the encouragement of trade union membership, and the maintenace of wage levels.

The Reform component included the creation of the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, which had the immediate purpose of restoring confidence in the country's banks and the longer term purpose of regulating their conduct; and the setting up of the Securites and Exchange Commission to regulsate other parts of it financial system.

By 1934, the Supreme Court began declaring significant parts of the New Deal unconstitutional. The programs were quickly fixed to pass muster, but in 1937 Roosevelt stunned the nation by a surpise proposal to pack the Supreme Court by adding five new justices. The proposal failed and Roosevelt permanently alienated many conservative Democrats; however the Supreme Court started upholding New Deal laws. Justices then started retiring, allowing Roosevelt to selected a majority of the Court. By 1942, the Supreme Court had almost completely abandoned its "judicial activism" of striking down congressional laws. The Supreme Court ruled in Wickard v. Filburn that the Commerce Clause covered almost all such regulation allowing the necessary expansion of federal power to make the New Deal "constitutional".

The Origins of the New Deal

Upon accepting the 1932 Democratic nomination for president, Roosevelt promised "a new deal for the American people."[1] Roosevelt entered office with no single ideology or plan for dealing with the depression. He was willing to try anything, and, indeed, in the "First New Deal" (1933-34) virtually every organized group (except the Socialists and Communists) gained much of what they demanded. This "First New Deal" thus was self-contradictory, pragmatic, and experimental.

The First Hundred Days

The "Bank Holiday" and the Emergency Banking Act

By March 4, all banks in the country were virtually closed by their governors, and Roosevelt kept them all closed until he could pass new legislation.[2] On March 9, Roosevelt sent to Congress the Emergency Banking Act, drafted in large part by Hoover's administration; the act was passed and signed into law the same day. It provided for a system of reopening sound banks under Treasury supervision, with federal loans available if needed. Three-quarters of the banks in the Federal Reserve System reopened within the next three days. Billions of dollars in "hoarded" currency and gold flowed back into them within a month, thus stabilizing the banking system. All was normal by April. During all of 1933, 4,004 small local banks were permanently closed and were merged into larger banks. (Their depositors eventually received 85 cents on the dollar of their deposits.) Congress created the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation in June, which insured deposits for up to $5,000, although Roosevelt opposed it support was overwhelming. The establishment of the FDIC virtually ended the era of "runs" on banks.

The Economy Act

The Economy Act, was passed on March 20, 1933. The act proposed to balance the "regular" (non-emergency) federal budget by cutting the salaries of government employees and cutting pensions to veterans by 40 percent. It saved $500 million a year and reassured deficit hawks such as Douglas that the new president was fiscally conservative. Roosevelt argued there were two budgets: the "regular" federal budget, which he balanced, and the "emergency budget," which was needed to defeat the depression.

The Farm Programs

This program began with the Agricultural Adjustment Act, creating the Agricultural Adjustment Administration (AAA), which Congress passed in May 1933. The AAA implemented a provision for crop reductions known as the "domestic allotment" system of the act. Under this system producers of corn, cotton, dairy products, hogs, rice, tobacco, and wheat would decide on production limits for their crops. The AAA would then pay land owners subsidies for leaving some of their land idle with funds provided by a new tax on food processing. Farm prices were to be subsidized up to the point of parity. Some crops were ordered to be destroyed and some livestock slaughtered to maintain prices. Farm incomes increased significantly in the first three years of the New Deal. However, consumers bore the brunt of higher food prices and were "horrified with its policy of enforced scarcity."[3] A Gallup Poll printed in the Washington Post revealed that a majority of the American public opposed the AAA.[4]

Roosevelt, Eleanor Roosevelt, and many New Dealers were highly sympathetic to the marginal farmers who lived on the land in severe poverty, especially in the South. Major programs addressed to their needs included the Resettlement Administration (RA), the Farm Security Administration (FSA), the Rural Electrification Administration (REA), the Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA) and rural welfare projects sponsored by the WPA, NYA, Forest Service and CCC, including school lunches, building new schools, opening roads in remote areas, reforestation, and purchase of marginal lands to enlarge national forests.

In 1936, the Supreme Court declared the AAA to be unconstitutional, stating that "a statutory plan to regulate and control agricultural production, [is] a matter beyond the powers delegated to the federal government..." The AAA was replaced by a similar program that did win Court approval. Federal regulation of agricultural production has been modified many times since then, but together with large subsidies it is still in effect in 2007.

Great Infrastructure Projects

The best of big "hard" infrastructure projects being carried out under the New Deal examples are the results of the Public Works Administration (PWA) [5], a former U.S. government agency established by Congress as the Federal Administration of Public Works, pursuant to the National Industrial Recovery Act, and the almost legendary Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA) [6], both of which, President Roosevelt ran, more or less directly. The PWA became, with its "multiplier-effect" and first two-year budget of $3.3 billion (then an enormous sum), the driving force of America’s biggest construction effort up to that date. By June 1934 the agency had distributed its entire fund to 13,266 federal projects and 2,407 non-federal projects. For every worker on a PWA project, almost two additional workers were employed indirectly. The PWA accomplished the electrification of rural America, the building of canals, tunnels, bridges, highways, streets, sewage systems, and housing areas, as well as hospitals, schools, and universities; every year it used up roughly half of the concrete and one-third of the steel of the entire nation. [7]

The projects to develop the "hard" infrastructure of the country were flanked by measures to improve its "soft" counterpart: important social measures, which for the first time in U.S. history, established the concept of a minimum wage, created insurance for the unemployed, sick and old, established decent health care, and abolished child labor. The Works Progress Administration (later Work Projects Administration, abbreviated WPA), was created on May 6, 1935 by Presidential order (Congress funded it annually but did not set it up). It was the largest and most comprehensive New Deal agency, employing millions of people and affecting every locality. The crowning achievement of these measures was the Social Security Act of 1935. This law was overturned by the Supreme Court, so that Roosevelt had to pass it in another form the Wagner Act of 1935, the "Bill of Rights" of American labor. Many of the New Deal [8] regulations were abolished or scaled back in 1975-1985 in a bipartisan neoliberal wave of deregulation. However various of them, such as the Federal Housing Administration (FHA) [9], the Social Security Administration (SSA) [10] , the Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA) [6], the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) [11], the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) [12] and the so called Glass-Steagall Act sections of the original Banking Act of June 1933, (sections 16, 20, 21 and 32), which regulates Wall Street, won widespread support and continue to this day.

Relief

The administration launched a series of relief measures and welfare agencies to give meaningful jobs to the unemployed, especially unskilled laborers. The largest programs were the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC), the Civil Works Administration (CWA), the Federal Emergency Relief Administration (FERA), the National Youth Administration (NYA), and above all, the Works Progress Administration (WPA). The WPA employed a maximum of 3.3 million in November 1938.[13] However, even at this level of WPA employment, unemployment (counting WPA as employment) was still 12.5% in 1938 according to figures from Micheal Darby.[14] All these emergency programs were terminated in 1942-43, when unemployment had vanished due to World War II related employment offers.

Reform: (NIRA)

Business, labor, and government cooperation

The Roosevelt administration insisted that business would have to ensure that the incomes of workers would rise along with their prices. The product of all these impulses and pressures was the National Industrial Recovery Act (NIRA) which was passed by Congress in June 1933. The NIRA established the National Planning Board, also called the National Resources Planning Board (NRPB), to assist in planning the economy by providing recommendations and information. Fredric A. Delano was appointed head of the NRPB.

The NIRA guaranteed to workers the right of collective bargaining and helped spur some union organizing activity, but much faster growth of union membership came after the 1935 Wagner Act. The NIRA established the National Recovery Administration (NRA), which attempted to stabilize prices and wages through cooperative "code authorities" involving government, business, and labor. The NRA included a multitude of regulations imposing the pricing and production standards for all sorts of goods and services. Some ridiculed it as the "National Run Around." Most economists were dubious because it was based on fixing prices to reduce competition.[15] Historian Jim Power, in FDR's Folly says that the above-market wage rates dictated by the NRA made it more expensive for employers to hire people, and therefore unnecessarily maintained high unemployment and prolonged the Depression.

To prime the pump and cut unemployment, the NIRA created the Public Works Administration (PWA), a major program of public works. From 1933 to 1939 PWA spent $6 billion with private companies to build 34,500 projects, many of them quite large.

The NRA "Blue Eagle" campaign

At the center of the NIRA was the National Recovery Administration (NRA), headed by former General Hugh Samuel Johnson. Johnson called on every business establishment in the nation to accept a stopgap "blanket code": a minimum wage of between 20 and 40 cents an hour, a maximum workweek of 35 to 40 hours, and the abolition of child labor. Johnson and Roosevelt contended that the "blanket code" would raise consumer purchasing power and increase employment.

The NRA negotiated specific sets of codes with leaders of the nation's major industries; the most important provisions were anti-deflationary floors below which no company would lower prices or wages, and agreements on maintaining employment and production. In a remarkably short time, the NRA won agreements from almost every major industry in the nation. Six months after the NRA went into effect industrial production dropped 25 percent.

On May 27 1935, the NRA was found to be unconstitutional by a unanimous decision of the U.S. Supreme Court in the case of Schechter v. United States.[16]

Second New Deal

Legislative successes and failures

The National Labor Relations Act (July 5), also known as the Wagner Act, revived and strengthened the protections of collective bargaining contained in the original (and now unconstitutional) NIRA. The result was a tremendous growth of membership in the labor unions comprising the American Federation of Labor. Labor thus became a major component of the New Deal political coalition. Roosevelt nationalized unemployment relief through the Works Progress Administration (WPA), headed by close friend Harry Hopkins. It created hundreds of thousands of low-skilled blue collar jobs for unemployed men (and some for unemployed women and white collar workers). Applicants for WPA jobs did not have to be Democrats, but their foremen quickly explained that Roosevelt created their paychecks and that conservative Republicans wanted to abolish the program. The National Youth Administration was the semi-autonomous WPA program for youth. In the very long run, the most important program of 1935, and perhaps the New Deal as a whole, was the Social Security Act (August 14), which established a system of universal retirement pensions, unemployment insurance, and welfare benefits for poor families and the handicapped. It established the framework for the U.S. welfare system. Roosevelt insisted that it should be funded by payroll taxes rather than from the general fund; he said, "We put those payroll contributions there so as to give the contributors a legal, moral, and political right to collect their pensions and unemployment benefits. With those taxes in there, no damn politician can ever scrap my social security program." One of the last New Deal agencies was the United States Housing Authority, created in 1937 with some Republican support to abolish slums.

Defeat: Court Packing and Executive Reorganization

Roosevelt, however, emboldened by the triumphs of his first term, set out in 1937 to consolidate authority within the government in ways that provoked powerful opposition. Early in the year, he asked Congress to expand the number of justices on the Supreme Court so as to allow him to appoint members sympathetic to his ideas and hence tip the ideological balance of the Court. This proposal provoked a storm of protest.

In one sense, however, it succeeded; Justice Owen Roberts, switched positions and began voting to uphold New Deal measures, effectively creating a liberal majority in West Coast Hotel Co. v. Parrish and National Labor Relations Board v. Jones & Laughlin Steel Corporation thus departing from the Lochner v. New York era and giving the government more power in questions of economic policies. Journalists called this change "the switch in time that saved nine." Recent scholars have noted that since the vote in Parrish took place several months before the court-packing plan was announced, other factors, like evolving jurisprudence, must have contributed to the Court's swing. The opinions handed down in Spring 1937, favorable to the government, also contributed to the downfall of the plan. In any case, the "court packing plan," as it was known, did lasting political damage to Roosevelt and was finally rejected by Congress in July.

At about the same time, the administration proposed a plan to reorganize the executive branch in ways that would significantly increase the president's control over the bureaucracy. Like the Court-packing plan, executive reorganization garnered opposition from those who feared a "Roosevelt dictatorship" and it failed in Congress; a watered-down version of the bill finally won passage in 1939.

Government Role: balance labor, business and farming

The government was now committed to providing at least minimal assistance to the poor and unemployed; to protecting the rights of labor unions; to stabilizing the banking system; to building low-income housing; to regulating financial markets; to subsidizing agricultural production; and to doing many other things that had not previously been federal responsibilities.

Thus, perhaps the strongest legacy of the New Deal, in other words, was to make the federal government a protector of interest groups and a supervisor of competition among them. As a result of the New Deal, political and economic life became politically more competitive than before, with workers, farmers, consumers, and others now able to press their demands upon the government in ways that in the past had been available only to the corporate world. Hence the frequent description of the government the New Deal created as the "broker state," a state brokering the competing claims of numerous groups. If there was more political competition, there was less market competition. Farmers were not allowed to sell for less than the official price. The transportation industry (especially airlines, trucking and railroads) was tightly regulated so that every firm had a guaranteed market and management and labor had high profits and high wages, all at the cost of high prices and much inefficiency. Quotas in the oil industry were fixed by the Railroad Commission of Texas with the federal Connally Hot Oil Act of 1935[17] guaranteeing that illegal "hot oil" would not be sold. To the New Dealers, the free market meant "cut-throat competition" and they considered that evil. Not until the 1970s and 1980s would most of the New Deal regulations be relaxed.

A major result of the full employment at high wages was a sharp, permanent decrease in the level of income inequality. The gap between rich and poor narrowed dramatically in the area of nutrition, because food rationing and price controls guaranteed a reasonably priced diet to everyone. Large families that had been poverty-stricken in the 1930s had four or five or more workers, and shot to the top one-third income bracket. Overtime made for huge paychecks in the munitions factories; white collar workers were fully employed too, but they did not receive overtime and their salary scale was no longer much higher than the blue collar wage scale.

Conflicting interpretation of the New Deal economic policies

Depression Statistics

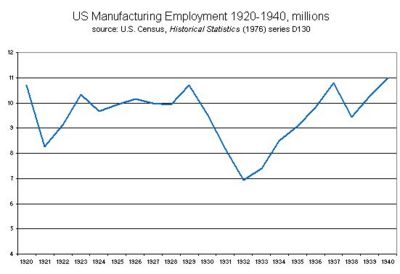

[18] however, recovery was slow --by 1939 GDP per adult was still 27% below trend.[19] And, throughout the New Deal the median joblessness rate was 17.2 percent and never went below 14 percent.

Relief Statistics

Table 3: Families on Relief 1936-41:

Prolonged/Worsened the Depression

A 1995 survey of economic historians and economists asked "Taken as a whole, government policies of the New Deal served to lengthen and deepen the Great Depression." Of the economists 27% agreed and 51% disagreed. Of the economic historians, only 6% agreed and 74% disagreed. (the rest were in the partly agree/disagree group).[20]

The minority view is represented by Harold L. Cole and Lee E. Ohanian who conclude that the "New Deal labor and industrial policies did not lift the economy out of the Depression as President Roosevelt and his economic planners had hoped," but that the "New Deal policies are an important contributing factor to the persistence of the Great Depression." They conclude that the New Deal "cartelization policies are a key factor behind the weak recovery." They say that the "abandonment of these policies coincided with the strong economic recovery of the 1940s."[21] Lowell E. Gallaway and Richard K. Vedder conclude that the "Great Depression was very significantly prolonged in both its duration and its magnitude by the impact of New Deal programs." They argue that without Social Security, work relief, unemployment insurance, and especially without the labor unions, business would have hired more workers and the unemployment rate would have been lower. [22] Few economists or economic historians have agreed with these speculations. The New Deal years 1933-36 (or indeed the FDR years 1933-45) showed the highest growth rates in the history of the American economy.

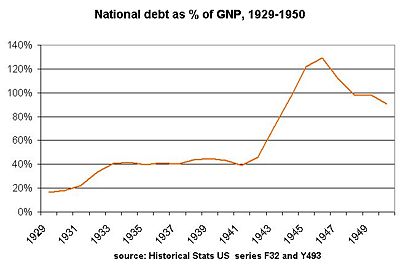

National Debt

The New Deal tried public works, farm subsidies and other devices to reduce unemployment, but FDR never completely gave up trying to balance the budget.

Apart from building up labor unions, the New Deal did not substantially alter the distribution of power within American capitalism.

Keynes visited to the White House in 1934 to urge President Roosevelt to do more deficit spending. Roosevelt complained to Labor Secretary Frances Perkins, "He left a whole rigmarole of figures--he must be a mathematician rather than a political economist."

Fiscal Conservatism

Fiscal conservatism was a key component of the New Deal, as Zelizer (2000) demonstrates. It was supported by Wall Street and local investors and most of the business community; mainstream academic economists believed in it, as apparently did the majority of the public. Conservative southern Democrats, who favored balanced budgets and opposed new taxes, controlled Congress and its major committees. Even liberal Democrats at the time regarded balanced budgets as essential to economic stability in the long run, although they were more willing to accept short-term deficits. Public opinion polls consistently showed public opposition to deficits and debt. Throughout his terms, Roosevelt recruited fiscal conservatives to serve in his administration, most notably Lewis Douglas the Director of Budget from 1933 to 1934, and Henry Morgenthau Jr., Secretary of the Treasury from 1934 to 1945. They defined policy in terms of budgetary cost and tax burdens rather than needs, rights, obligations, or political benefits. Personally the president embraced their fiscal conservatism. Politically, he realized that fiscal conservatism enjoyed a strong wide base of support among voters, leading Democrats, and businessmen. On the other hand there was enormous pressure to act–and spending money on high visibility programs attracted Roosevelt, especially if it tied millions of voters to him, as did the WPA.

The Economy Act of 1933, passed early in the Hundred Days, was Douglas' great achievement. It reduced federal expenditures by $500 million, to be achieved by reducing veterans’ payments and federal salaries. Douglas cut government spending through executive orders that cut the military budget by $125 million, $75 million from the Post Office, $12 million from Commerce, $75 million from government salaries, and $100 million from staff layoffs. As Freidel concludes, "The economy program was not a minor aberration of the spring of 1933, or a hypocritical concession to delighted conservatives. Rather it was an integral part of Roosevelt's overall New Deal."[23] Revenues were so low that borrowing was necessary (only the richest 3% paid any income tax before 1942.) .

Morgenthau shifted with FDR, but at all times tried to inject fiscal responsibility; he deeply believed in balanced budgets, stable currency, reduction of the national debt, and the need for more private investment . The Wagner Act met Morgenthau’s requirement because it strengthened the party’s political base and involved no new spending. In contrast to Douglas, Morgenthau accepted Roosevelt’s double budget as legitimate–that is a balanced regular budget, and an “emergency” budget for agencies, like the WPA, PWA and CCC, that would be temporary until full recovery was at hand. He fought against the veterans’ bonus until Congress finally overrode Roosevelt’s veto and gave out $2.2 billion in 1936. His biggest success was the new Social Security program; he managed to reverse the proposals to fund it from general revenue and insisted it be funded by new taxes on employees. It was Morgenthau who insisted on excluding farm workers and domestic servants from Social Security because workers outside industry would not be paying their way.[24]

- ↑ The phrase came from the title of popular writer Stuart Chase's book A New Deal published earlier in 1932.

- ↑ for details see "Bottom" in Time Magazine (March 13, 1933) online at [1]

- ↑ Cushman, Barry (1998). Rethinking the New Deal Court. Oxford University Press. p. 34

- ↑ Cushman, Barry (1998). Rethinking the New Deal Court. Oxford University Press. p. 34

- ↑ PWA - Public Works Administration,The Columbia Encyclopedia, Sixth Edition, 2001-05]

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 TVA - Tennessee Valley Authority: From the New Deal to a New Century]

- ↑ McJIMSEY, George. The Presidency of Franklin Delano Rooselvelt, American Presidency Series. University Press of Kanasas, April 2000. ISBN 978-0-7006-1012-9

- ↑ ROSENOF, Theodore. Economics in the Long Run: New Deal Theorists and Their Legacies, 1933-1993. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1997. ISBN 0-8078-2315-5.

- ↑ Federal Housing Administration

- ↑ SSA - U. S. Social Security Administration

- ↑ FDIC - Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation

- ↑ SEC - U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission

- ↑ According to Nancy Rose' Put to Work.

- ↑ Darby, Michael R.Three and a half million U.S. Employees have been mislaid: or, an Explanation of Unemployment, 1934-1941. Journal of Political Economy 84, no. 1 (1976): 1-16.

- ↑ Parker

- ↑ On that same day, the Court unanimously struck down as unconstitutional the Frazier-Lemke Act that put a moratorium on farm mortgages.

- ↑ The Handbook of Texas Online: Connally Hot Oil Act of 1935

- ↑ Angus Maddison, The World Economy: Historical Statistics (OECD 2003); Japan is close, see p 174

- ↑ Cole, Harold L and Ohanian, Lee E. New Deal Policies and the Persistence of the Great Depression: A General Equilibrium Analysis, 2004.

- ↑ See [2]

- ↑ Cole, Harold L and Ohanian, Lee E. New Deal Policies and the Persistence of the Great Depression: A General Equilibrium Analysis, 2004.

- ↑ Gallaway, Lowell E. and Vedder, Richard K. Out of Work: Unemployment and Government in Twentieth-Century America, New York University Press; Updated edition (July 1997).

- ↑ Freidel 1990, p. 96

- ↑ Zelizer 2000; Savage 1998