Gertrude Stein: Difference between revisions

imported>Pat Palmer (more to the intro) |

mNo edit summary |

||

| (53 intermediate revisions by 2 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{subpages}} | {{subpages}} | ||

{{Authors|Pat Palmer|others=n}} | {{Authors|Pat Palmer|others=n}} | ||

{{ | {{TOC|right}} | ||

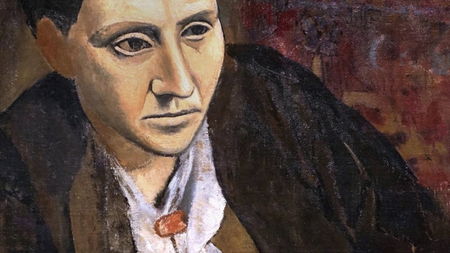

{{Image|Gertrude stein-1.jpg|left|450px|Part of [[Pablo Picasso|Picasso]]'s famous 1905-06 portrait of Gertrude Stein}} | {{Image|Gertrude stein-1.jpg|left|450px|Part of [[Pablo Picasso|Pable Picasso]]'s famous 1905-06 portrait of Gertrude Stein. Picasso was one of Stein's friends during her Paris years.<ref>Read more about ''<span class="newtab">[https://art473modernarti.com/2020/09/22/portrait-of-gertrude-stein-by-pablo-picasso/comment-page-1/ Portrait of Gertrude Stein…by Pablo Picasso]</span>'', blog post by an art history professor from September 22, 2020, last access 2/6/2021</ref>}} | ||

{{Image|Terra cotta stein.jpg|right|450px|[[Jo Davidson (sculptor)]]'s life-size terra cotta sculpture of Gertrude Stein created in Paris in 1923, now in the Smithsonian National Portrait Gallery. A bronze cast of this sculture was made in 1991 for Bryant Park, Manhattan, New York City. "There was an eternal quality about her," sculptor Jo Davidson (a Stein friend from her Paris years) wrote. "She somehow symbolized wisdom." He depicted her here as "a sort of modern Buddha." }} | |||

'''Gertrude Stein''' (1874 - 1946) was an American author who lived in [[ | '''Gertrude Stein''' (1874 - 1946) was an American author, and self-proclaimed genius, who lived in [[France]] for most of her adult life. For decades after her death, Stein was best remembered for her associations with, and promotions of, several famous writers and artists, as well as for having lived an openly lesbian lifestyle. As of 2021, there exists a renewed and widespread interest in her writings, in which she frequently created deliberate linguistic conundrums, making her work especially challenging to read. Her writings have also become popular as a source of out-of-context quotes in the internet, with the specific work rarely cited. | ||

Many English literature majors in college were never required to read a single work by Stein, who arguably may be the most misquoted and least read writer of the English language. | |||

== Most famous work == | == Most famous work == | ||

Stein's most famous work was a best seller published in 1933, ''The Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas'', and it | Stein's most famous work was a best seller published in 1933, ''The Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas'', and it uses relatively little of the kind of confounding language that has caused Gertrude Stein to be remembered nearly a century later. | ||

== | == A decidedly not famous work == | ||

Stein's least famous | One of Stein's least famous books was published posthumously in 1947 and was entitled ''Four in America''<ref>''Four in America'' was published in 1947 by Yale University Press. The book includes a 26-page introduction by playwright [[Thornton Wilder]].</ref>. As of 2020, ''Four in America'' is out of print, has never been digitized, and is likely to be found in only two or three libraries in the United States<ref>A copy of ''Four in America'' exists in the <span class="newtab">[https://www.freelibrary.org/ Philadelphia Free Library]</span>, and also in the <span class="newtab">[https://library.princeton.edu/ Princeton University Library]</span></ref>. Even used copies via the internet are difficult to come by. The book consisted of four sections, purporting to be about “Wilbur Wright”, "Grant", “Henry James” and “George Washington”. | ||

''Four in America'' is | ''Four in America'' is noteworthy because a single sentence of it has been widely misquoted and misinterpreted multiple times on the internet, all without any reference to its actual source. Internet quotes claim that Stein said she "admired Ulysses S. Grant". Others claim that Stein said she could not “think of Grant without weeping”. The actual sentence Stein wrote is to be found in the quarter of ''Four in America'' allegedly about Grant, on its last page, atop the following abstruse paragraph: | ||

{|align="center" cellpadding="10" style="background-color:#FFFFCC; width: | {|align="center" cellpadding="10" style="background-color:#FFFFCC; width:40%; border: 1px solid #aaa; margin:20px; font-size: 95%;" | ||

| | | | ||

I cannot think of Ulysses Simpson Grant without tears. He was so what shall it be not by any night not by any day not by any light not by any way, but Ulysses Simpson Grant, which one is, that one is, who can come that one can come, for which they come not of for which they come but they can in that case but which they can in that case can place, I place him there. Do you too. Do you two place him there which do you do. I do I place him there. I which I place him there, not only for me to be me, I am an American which if which I can be only I know, I know all about sitting and standing but I do not sit and stand in the way not yet nor has been. | '''I cannot think of Ulysses Simpson Grant without tears.''' He was so what shall it be not by any night not by any day not by any light not by any way, but Ulysses Simpson Grant, which one is, that one is, who can come that one can come, for which they come not of for which they come but they can in that case but which they can in that case can place, I place him there. Do you too. Do you two place him there which do you do. I do I place him there. I which I place him there, not only for me to be me, I am an American which if which I can be only I know, I know all about sitting and standing but I do not sit and stand in the way not yet nor has been. | ||

From Four in America, page 81, by Gertrude Stein (1947). | From Four in America, page 81, by Gertrude Stein (1947). | ||

|} | |} | ||

An attempt to make sense of the above paragraph can be found in ''Four in America'''s 26-page introduction by [[Thornton Wilder]]. He provides an explanation for Stein’s mangled, rebellious and challenging use of language. Per Wilder, Stein believed that we are now living in “end times” where language has become superficial in effect, and normal use of language does not reach the real person inside each of us. Thus (surmises Wilder), Stein tried a variety of unorthodox mechanisms to cut through our mental fog, to make us sit up and think differently, to jar us out of complacency, to challenge what we really know. Possibly, to want to read this book, wrote Wilder, requires a kind spiritual readiness. | An attempt to make sense of the above paragraph can be found in ''Four in America'''s 26-page introduction by [[Thornton Wilder]] (whom Stein counted as a friend, and who appreciated her writing). He provides an explanation for Stein’s mangled, rebellious and challenging use of language. Per Wilder, Stein believed that we are now living in “end times” where language has become superficial in effect, and normal use of language does not reach the real person inside each of us. Thus (surmises Wilder), Stein tried a variety of unorthodox mechanisms to cut through our mental fog, to make us sit up and think differently, to jar us out of complacency, to challenge what we really know. Possibly, to want to read this book, wrote Wilder, requires a kind spiritual readiness. | ||

== | == Frequently quoted == | ||

Stein | Scattered throughout Stein's writings are some striking phrases that have become very popular. Although many are from works filled with difficult and marginally comprehensible language, people repeat these phrases (or mangled versions of them) and often provide a convenient explanation of what Stein meant--but seldom does anyone cite the work from which the phrase came, and so these attributions of specific meanings tend to be questionable. | ||

{|align="center" cellpadding="10" style="background-color:#FFFFCC; width: | {|align="center" cellpadding="10" style="background-color:#FFFFCC; width:40%; border: 1px solid #aaa; margin:20px; font-size: 95%;" | ||

| | | | ||

'''A vegetable garden in the beginning looks so promising and then after all little by little it grows nothing but vegetables, nothing, nothing but vegetables.''' | '''A vegetable garden in the beginning looks so promising and then after all little by little it grows nothing but vegetables, nothing, nothing but vegetables.''' | ||

| Line 33: | Line 36: | ||

|} | |} | ||

{|align="center" cellpadding="10" style="background-color:#FFFFCC; width: | {|align="center" cellpadding="10" style="background-color:#FFFFCC; width:40%; border: 1px solid #aaa; margin:20px; font-size: 95%;" | ||

| | | | ||

'''Let me listen to me and not to them.''' | '''Let me listen to me and not to them.''' | ||

| Line 40: | Line 43: | ||

|} | |} | ||

The following is frequently misquoted as '''''A''' rose is a rose is a rose''. | |||

{|align="center" cellpadding="10" style="background-color:#FFFFCC; width:40%; border: 1px solid #aaa; margin:20px; font-size: 95%;" | |||

{|align="center" cellpadding="10" style="background-color:#FFFFCC; width: | |||

| | | | ||

'''Rose is a rose is a rose is a rose.'''<ref>From [http://www.gutenberg.org/cache/epub/33403/pg33403.txt Project Gutenberg: ''Geography and Plays'' by Gertrude Stein], last access 2/6/2021</ref> | |||

From | From the poem "Sacred Emily", by Gertrude Stein (first appearance 1913)<ref>More about "Rose is a rose is a rose" is in the University of Pennsylvania's <span class="newtab">[http://writing.upenn.edu/library/Stein-Gertrude_Rose-is-a-rose.html Electronic Poetry Center]</span>, last access 2-5-2021</ref> | ||

|} | |} | ||

The last five words of this sentence, written in regards to Stein's childhood home in Oakland, CA, have caught the public imagination as a standalone phrase since the 1960's. The phrase now tends to mean that something has no important essence. | |||

{|align="center" cellpadding="10" style="background-color:#FFFFCC; width: | {|align="center" cellpadding="10" style="background-color:#FFFFCC; width:40%; border: 1px solid #aaa; margin:20px; font-size: 95%;" | ||

| | | | ||

...Not of course the house, the house the big house and the big garden and the eucalyptus trees and the rose hedge naturally were not there any longer existing, what was the use of my having come from Oakland it was not natural to have come from there yes write about it if I like or any- thing if I like but not there, '''there is no there there'''. | |||

From | From ''Everybody’s Autobiography'', p 298, by Gertrude Stein (1937).<ref>See more details in <span class="newtab">[https://www.wsj.com/articles/why-gertrude-steins-no-there-there-is-everywhere-1517589198 ''Why Gertrude Stein’s ‘No There There’ Is Everywhere'']</span>, ''Wall Street Journal'', Feb. 2, 2018, last access 2/6/2021</ref> | ||

|} | |} | ||

The following | The following oft-quoted phrase appears during a description of a frought day in the early 1930's when two cars would not start, the telephone was broken, there was no food, visitors arrived, their two house servants resigned, and no one was getting anything they wanted at that time: | ||

{|align="center" cellpadding="10" style="background-color:#FFFFCC; width: | {|align="center" cellpadding="10" style="background-color:#FFFFCC; width:40%; border: 1px solid #aaa; margin:20px; font-size: 95%;" | ||

| | | | ||

The thing about it all that is puzzling is that really nothing is frightening. Anything scares me, anything scares any one but really after all '''considering how dangerous everything is nothing is really very frightening'''. | |||

From | From ''Everybody's Autobiography'', Ch. II, page 75, by Gertrude Stein (1937). | ||

|} | |} | ||

== Notes == | == Notes ==[[Category:Suggestion Bot Tag]] | ||

Latest revision as of 16:01, 21 August 2024

Authors [about]:

join in to develop this article! |

Gertrude Stein (1874 - 1946) was an American author, and self-proclaimed genius, who lived in France for most of her adult life. For decades after her death, Stein was best remembered for her associations with, and promotions of, several famous writers and artists, as well as for having lived an openly lesbian lifestyle. As of 2021, there exists a renewed and widespread interest in her writings, in which she frequently created deliberate linguistic conundrums, making her work especially challenging to read. Her writings have also become popular as a source of out-of-context quotes in the internet, with the specific work rarely cited.

Many English literature majors in college were never required to read a single work by Stein, who arguably may be the most misquoted and least read writer of the English language.

Most famous work

Stein's most famous work was a best seller published in 1933, The Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas, and it uses relatively little of the kind of confounding language that has caused Gertrude Stein to be remembered nearly a century later.

A decidedly not famous work

One of Stein's least famous books was published posthumously in 1947 and was entitled Four in America[2]. As of 2020, Four in America is out of print, has never been digitized, and is likely to be found in only two or three libraries in the United States[3]. Even used copies via the internet are difficult to come by. The book consisted of four sections, purporting to be about “Wilbur Wright”, "Grant", “Henry James” and “George Washington”.

Four in America is noteworthy because a single sentence of it has been widely misquoted and misinterpreted multiple times on the internet, all without any reference to its actual source. Internet quotes claim that Stein said she "admired Ulysses S. Grant". Others claim that Stein said she could not “think of Grant without weeping”. The actual sentence Stein wrote is to be found in the quarter of Four in America allegedly about Grant, on its last page, atop the following abstruse paragraph:

|

I cannot think of Ulysses Simpson Grant without tears. He was so what shall it be not by any night not by any day not by any light not by any way, but Ulysses Simpson Grant, which one is, that one is, who can come that one can come, for which they come not of for which they come but they can in that case but which they can in that case can place, I place him there. Do you too. Do you two place him there which do you do. I do I place him there. I which I place him there, not only for me to be me, I am an American which if which I can be only I know, I know all about sitting and standing but I do not sit and stand in the way not yet nor has been. From Four in America, page 81, by Gertrude Stein (1947). |

An attempt to make sense of the above paragraph can be found in Four in America's 26-page introduction by Thornton Wilder (whom Stein counted as a friend, and who appreciated her writing). He provides an explanation for Stein’s mangled, rebellious and challenging use of language. Per Wilder, Stein believed that we are now living in “end times” where language has become superficial in effect, and normal use of language does not reach the real person inside each of us. Thus (surmises Wilder), Stein tried a variety of unorthodox mechanisms to cut through our mental fog, to make us sit up and think differently, to jar us out of complacency, to challenge what we really know. Possibly, to want to read this book, wrote Wilder, requires a kind spiritual readiness.

Frequently quoted

Scattered throughout Stein's writings are some striking phrases that have become very popular. Although many are from works filled with difficult and marginally comprehensible language, people repeat these phrases (or mangled versions of them) and often provide a convenient explanation of what Stein meant--but seldom does anyone cite the work from which the phrase came, and so these attributions of specific meanings tend to be questionable.

|

A vegetable garden in the beginning looks so promising and then after all little by little it grows nothing but vegetables, nothing, nothing but vegetables. From Wars I Have Seen, page 39, by Gertrude Stein (1945). |

|

Let me listen to me and not to them. From Stanzas in Meditation Stanza VII, by Gertrude Stein (1932)[4] |

The following is frequently misquoted as A rose is a rose is a rose.

|

Rose is a rose is a rose is a rose.[5] From the poem "Sacred Emily", by Gertrude Stein (first appearance 1913)[6] |

The last five words of this sentence, written in regards to Stein's childhood home in Oakland, CA, have caught the public imagination as a standalone phrase since the 1960's. The phrase now tends to mean that something has no important essence.

|

...Not of course the house, the house the big house and the big garden and the eucalyptus trees and the rose hedge naturally were not there any longer existing, what was the use of my having come from Oakland it was not natural to have come from there yes write about it if I like or any- thing if I like but not there, there is no there there. From Everybody’s Autobiography, p 298, by Gertrude Stein (1937).[7] |

The following oft-quoted phrase appears during a description of a frought day in the early 1930's when two cars would not start, the telephone was broken, there was no food, visitors arrived, their two house servants resigned, and no one was getting anything they wanted at that time:

|

The thing about it all that is puzzling is that really nothing is frightening. Anything scares me, anything scares any one but really after all considering how dangerous everything is nothing is really very frightening. From Everybody's Autobiography, Ch. II, page 75, by Gertrude Stein (1937). |

== Notes ==

- ↑ Read more about Portrait of Gertrude Stein…by Pablo Picasso, blog post by an art history professor from September 22, 2020, last access 2/6/2021

- ↑ Four in America was published in 1947 by Yale University Press. The book includes a 26-page introduction by playwright Thornton Wilder.

- ↑ A copy of Four in America exists in the Philadelphia Free Library, and also in the Princeton University Library

- ↑ More about "Let me listen to me..." is at the Google Books page for Stanzas in Meditation: The Corrected Edition by Gertrude Stein, Yale University Press, Jan 17, 2012; last access 2/5/2021

- ↑ From Project Gutenberg: Geography and Plays by Gertrude Stein, last access 2/6/2021

- ↑ More about "Rose is a rose is a rose" is in the University of Pennsylvania's Electronic Poetry Center, last access 2-5-2021

- ↑ See more details in Why Gertrude Stein’s ‘No There There’ Is Everywhere, Wall Street Journal, Feb. 2, 2018, last access 2/6/2021