User:John R. Brews/Reality: Difference between revisions

Jump to navigation

Jump to search

imported>John R. Brews No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| (23 intermediate revisions by one other user not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{AccountNotLive}} | |||

{{TOC|right}} | {{TOC|right}} | ||

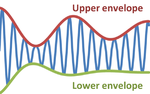

{{Image|Signal envelopes.png|right|150px|Top and bottom envelope functions for a modulated sine wave.}} | |||

In [[physics]] and [[engineering]] the '''envelope''' of a rapidly varying signal is a smooth curve outlining its extremes in amplitude.<ref name=Johnson/> The figure illustrates a sine wave varying between an upper and a lower envelope. | |||

In | |||

==Notes== | ==Notes== | ||

{{reflist|group=Note|refs= | {{reflist|group=Note|refs= | ||

}} | }} | ||

==References== | ==References== | ||

{{ | {{reflist|refs= | ||

<ref name= | <ref name=Johnson> | ||

{{cite book |title= | {{cite book |title=Software Receiver Design: Build Your Own Digital Communication System in Five Easy Steps |url=http://books.google.com/books?id=LNea1qui1KcC&pg=PA417 |pages=p. 417 |chapter=Figure C.1: The envelope of a function outlines its extremes in a smooth manner |author=C. Richard Johnson, Jr, William A. Sethares, Andrew G. Klein |isbn=0521189446 |year=2011 |publisher=Cambridge University Press}} | ||

</ref> | </ref> | ||

}} | }} | ||

Latest revision as of 03:07, 22 November 2023

The account of this former contributor was not re-activated after the server upgrade of March 2022.

In physics and engineering the envelope of a rapidly varying signal is a smooth curve outlining its extremes in amplitude.[1] The figure illustrates a sine wave varying between an upper and a lower envelope.

Notes

References

- ↑ C. Richard Johnson, Jr, William A. Sethares, Andrew G. Klein (2011). “Figure C.1: The envelope of a function outlines its extremes in a smooth manner”, Software Receiver Design: Build Your Own Digital Communication System in Five Easy Steps. Cambridge University Press, p. 417. ISBN 0521189446.