CZ:Featured article/Current: Difference between revisions

imported>Chunbum Park (→Papacy: Four color theorem) |

imported>John Stephenson (template) |

||

| (54 intermediate revisions by 4 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{:{{FeaturedArticleTitle}}}} | |||

<small> | |||

==Footnotes== | |||

}}< | |||

{{reflist|2}} | {{reflist|2}} | ||

</small> | |||

Latest revision as of 10:19, 11 September 2020

Telephone newspaper is a general term for the telephone-based news and entertainment services which were introduced beginning in the 1890s, and primarily located in large European cities. These systems were the first example of electronic broadcasting, and offered a wide variety of programming, however, only a relative few were ever established. Although these systems predated the invention of radio, they were supplanted by radio broadcasting stations beginning in the 1920s, primarily because radio signals were able to cover much wider areas with higher quality audio.

History

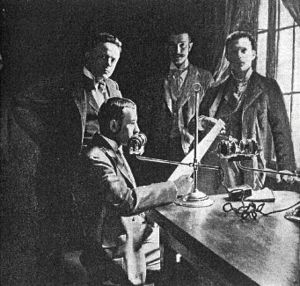

After the electric telephone was introduced in the mid-1870s, it was mainly used for personal communication. But the idea of distributing entertainment and news appeared soon thereafter, and many early demonstrations included the transmission of musical concerts. In one particularly advanced example, Clément Ader, at the 1881 Paris Electrical Exhibition, prepared a listening room where participants could hear, in stereo, performances from the Paris Grand Opera. Also, in 1888, Edward Bellamy's influential novel Looking Backward: 2000-1887 foresaw the establishment of entertainment transmitted by telephone lines to individual homes.

The scattered demonstrations were eventually followed by the establishment of more organized services, which were generally called Telephone Newspapers, although all of these systems also included entertainment programming. However, the technical capabilities of the time meant that there were limited means for amplifying and transmitting telephone signals over long distances, so listeners had to wear headphones to receive the programs, and service areas were generally limited to a single city. While some of the systems, including the Telefon Hirmondó, built their own one-way transmission lines, others, including the Electrophone, used standard commercial telephone lines, which allowed subscribers to talk to operators in order to select programming. The Telephone Newspapers drew upon a mixture of outside sources for their programs, including local live theaters and church services, whose programs were picked up by special telephone lines, and then retransmitted to the subscribers. Other programs were transmitted directly from the system's own studios. In later years, retransmitted radio programs were added.

During this era telephones were expensive luxury items, so the subscribers tended to be the wealthy elite of society. Financing was normally done by charging fees, including monthly subscriptions for home users, and, in locations such as hotel lobbies, through the use of coin-operated receivers, which provided short periods of listening for a set payment. Some systems also accepted paid advertising.

Footnotes