Stress and appetite: Difference between revisions

imported>Gareth Leng |

mNo edit summary |

||

| (66 intermediate revisions by 6 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{subpages}} | {{subpages}} | ||

Although [[stress]] is often thought of as those social and workplace pressures of modern living that can lead to ill health, stress can be defined as ''anything'' that is potentially damaging to the internal [[homeostasis]] of an organism. Stressors may be either emotional and physical. Emotional stressors can be anything from a novel environment to potential embarrassment; they involve the ''perception'' of the stimuli as being 'stressful' and are processed by the limbic forebrain. On the other hand, physical stressors, esuch as an acute infection or a sudden change in temperature, pose an immediate threat and are processed quickly by the caudal brainstem. | |||

The stress response involves activation of the [[hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal]] (HPA) axis, resulting in heightened vigilance, enhanced cognition and arousal of the [[autonomic nervous system]]. These responses help to protect the body and the brain from harmful effects of the stress stimuli. <ref>Habib KE ''et al.'' (2001) Neuroendocrinology of stress ''Endocrinology and Metabolic Clincs of North America'' 30:695-728 PMID 11571937</ref> | |||

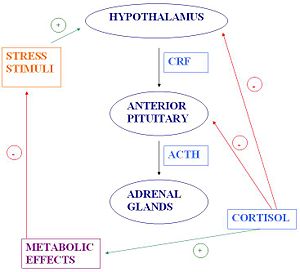

Activation of the HPA axis triggers a cascade which ultimately leads to the secretion of the [[glucocorticoid]] hormone [[cortisol]] from the [[adrenal cortex]]. Cortisol acts on many cells to influence gene transcription and hence protein synthesis, and it also has direct membrane effects on some cells. | |||

The | '''The HPA axis''' | ||

{{Image|Holly's_JPEG_Diagram.JPG|right|300px|}} | |||

The HPA axis is comprised of the [[hypothalamus]], the [[pituitary]] and the [[adrenal gland]]. The hypothalamus is the control centre for most of the hormonal systems in the body. In response to a stressor, be it psychological or physiological, [[corticotropin-releasing factor]] (CRF) is secreted. CRF is a peptide hormone which is synthesised by neuroendocrine neurones in the [[paraventricular nucleus]] (PVN) of the hypothalamus and released from the [[median eminence]] into capillaries that carry it to the pituitary gland (the hypothalamo-hypophysial portal vessels). There, CRF triggers secretion of [[adrenocorticotrophic hormone]] (ACTH). In turn, ACTH acts on the adrenal glands to stimulate the production of [[glucocorticoid]] hormones, of which [[cortisol]] is the main one in humans. Cortisol release triggers negative feedback to the hypothalamus and anterior pituitary, resulting in a fall in circulating ACTH, and subsequently a fall in glucocorticoid production. Cortisol also has metabolic effects which facilitate a return to [[homeostasis]]. | |||

== | ==Neural mechanisms of appetite control== | ||

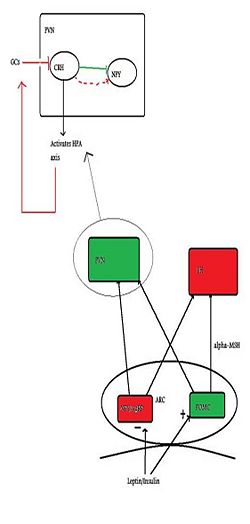

{{Image|Citizendium figure 2.jpg|right|250px| The basic neural control of appetite, with emphasis on the PVN and how it relates to the HPA axis. Green indicates anorexigenic pathways/neurons and red indicates orexigenic pathways.}} | |||

Several peptides circulating in the blood inform the brain about the body’s nutritional status. [[Insulin]] and [[leptin]], (which both suppress appetite) and [[ghrelin]] (which induces appetite) all can cross the blood-brain barrier, and one important site of action is at the [[arcuate nucleus]]. In the arcuate nucleus, some neurones produce substances which induce feeding (''orexigenic'') while others produce substances that suppress feeding (''anorexigenic''). The orexigenic neurons in the arcuate mucleus co-express two neuropeptides: [[neuropeptide Y]] (NPY), and [[Agouti-related peptide]] (AgRP), and these neurones are inhibited by leptin. Conversely, leptin excitates anorexigenic neurons that express [[pro-opiomelanocortin]] (POMC) triggering the release of [[alpha-MSH]], which acts at MC4 receptors to suppress feeding/hunger. AgRP is an inverse agonist at the MC4 receptor, thus increasing NPY/AgRP neurons orexigenic effect <ref>Schwartz M ''et al.'' (2000) Central nervous system control of food intake ''Nature'' 404:661-71 PMID 10766253</ref> | |||

Appetite-regulating neurons of the arcuate nucleus project to many other parts of the hypothalamus, including to the [[lateral hypothalamus]] (LH), and the [[paraventricular nucleus]] (PVN). PVN stimulation causes inhibition of eating, whilst LH stimulation has the opposite effect. It is in the PVN that the main activator of the HPA axis - [[corticotropin-releasing hormone]] (CRH) - is synthesised. NPY neurons have abundant projections to the PVN, and due to their close proximity to CRH cell bodies, NPY has a stimulatory effect on CRF release.<ref>Dimitrov EL ''et al.'' (2006) Involvement of neuropeptide Y Y1 receptors in the regulation of neuroendocrine corticotropin-releasing hormone neuronal activity ''Endocrinology'' 148:3666-73</ref> | |||

The key area of connection between the HPA axis and regulation of feeding is the PVN. Here, the innervation by NPY neurons influences CRF synthesis. CRF inhibits NPY neurones, thus initially CRF is anorexigenic, but glucocorticoids feed back to the brain to inhibit CRF expression. With sustained activation of the HPA axis, there is less CRF inhibition of NPY neurones, resulting in a greater orexigenic drive.<ref>Cavagnini F ''et al.'' (2000) Glucocorticoids and neuroendocrine function ''Int J Obesity'' 24: Suppl 2, s77-9 PMID 10997615</ref> | |||

The key area of connection between the HPA axis and regulation of feeding is the PVN. Here, | |||

==Acute Stress and Appetite== | ==Acute Stress and Appetite== | ||

Stress affects every body system and contributes to many contemporary health problems, including obesity.<ref> Habhab S ''et al.'' (2009) The relationship between | |||

stress, dietary restraint and food preference in women ''Appetite'' 52:437-44 </ref> | |||

Stress | |||

'' | |||

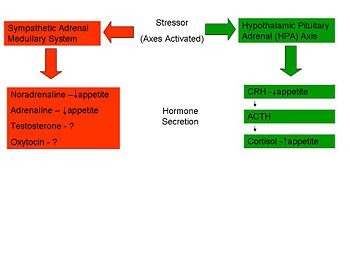

Stress can be put into two broad categories: acute stress (short term) and chronic stress (stressors occur regulary). We respond to acute stress sometimes by overeating, and sometimes by under-eating, and this may be linked to the particular type of stressor. <ref name=Torres07> Torres SJ,Nowson CA (2007) Relationship between stress, eating behaviour and obesity ''Nutrition'' 23:887-94 </ref> | |||

'''HPA Axis – ‘Uncontrollable Stress’''' | '''HPA Axis – ‘Uncontrollable Stress’''' | ||

Rodent studies | Rodent studies have illustrated a greater caloric intake during the recovery period from a novel stressor. An ‘uncontrollable stressor’ can lead to the activation of the HPA axis resulting in the immediate release of CRH. This stimulates the release of cortisol (corticosterone in rodents). <ref name=Torres07/> However, it is not known how cortisol triggers over-eating; studies have shown that there is no direct effect of cortisol but it may influence other factors such as leptin, NPY or certain cytokines which have a more direct effect on eating. <ref> Sapolsky R (1998) Why Zebras don't get ulcers; An Updated Guide to Stress, Stress-related Diseases and Coping. ''Freeman and Co'' 76-79 </ref> | ||

'''Sympathetic-Pituitary-Adrenal Axis – ‘Controllable Stress’''' | '''Sympathetic-Pituitary-Adrenal Axis – ‘Controllable Stress’''' | ||

Several studies have shown a ''suppression'' of eating in response to acute stress. In certain situations, sometimes termed ‘controllable’ stressors, the ‘Fight or Flight’ response is activated rather than the HPA axis. This mechanism, caused by the release of catecholamines (adrenaline and noradrenaline) from the adrenal glands, causes a range of physiological and behavioural changes to allow the individual to cope with the situation. One such change is a reduction in food intake through a slowed gastric emptying and shunting of the blood vessels to the gastrointestinal tract to allow the muscles an increased blood supply. <ref name=Torres07/> | |||

{{Image|Picture.jpg|right|350px|Image Caption}} | |||

Stress | ==Chronic Stress== | ||

Chronic stress is the brain’s response to unpleasant events over a long time (more than 24 hours). Examples of chronic stress include job pressures or mental health diseases. While acute stress results in an acute increase in ACTH and glucocorticoid secretion followed by a decrease, chronic stress is associated with a sustained increase in glucocorticoid production, that is associated with a blunting of the normal circadian variation in glucocorticoid production. The effects of chronic stress on the hypothalamus include an inportant change in the CRF neurones of the PVN; these show a markedly increased expression of [[vasopressin]] mRNA - their major secretory product changes from being mainly CRF to being mainly vasopressin. Vasopressin, like CRF is a secretagogue for ACTH; on its own it is less potent that CRF, but when vasopressin and CRF are present together they have powerfully synergistic effects on ACTH secretion. | |||

Elsewhere in the brain the chronically elevated glucocorticoids have important effects on the [[hippocampus]], and these are thought to underlie the effects of stress on cognitive function. There is also increased expression of CRF mRNA in the central amygdala, which enables the expression of the “Chronic stress-response network”. This results in an increase in ACTH and therefore corticosterone secretion. There is also an increase in glutamate secretion by the paraventricular nucleus of the thalamus. These structures were identified using c-Fos immunoreactive cells comparisons which were higher for chronically stressed rats than controls. | |||

There are other main effects of chronically high concentration of glucocorticoids <ref> Dallman MF ''et al.'' (2010) Chronic stress and obesity: a new view of ‘comfort food’ ''Proc Natl Acad Sci'' 100:11696–701</ref>. High levels of glucocorticoid activate mechanisms of coping such as increasing the stimulating of pleasurable/compulsive activities such as eating sugary foods and fats. An example of this is the urge to consume “comfort foods”. The combination of “comfort foods”, high insulin levels and high glucocorticoid levels increases abdominal fat depots. This can inhibit CRF mRNA expression in hypothalamic neurons and reduce HPA activity. This increased ingestion of “comfort foods” such as fatty and high sugar content foods and increased abdominal fat are strongly associated with obesity. | |||

Chronic stress can also lead to an overall decrease in the HPA axis’ ability to control hormone levels. | |||

In rats, severe chronic stress results in reduced intake of food. Moderate chronic stress also resultsin reduced food intake. It was shown that as CRF increases, there is a reduction in food ingestion and hence in body weight. | |||

Elevated glucocorticoids of exogenous or endogenous nature for extended periods of time can lead to [[Cushing’s syndrome]]. Experiments on rats suggest that the effects of an increase in corticosterone leads to increase in ingestion of foods with high fat and sugar contents. This causes systems such as upper body obesity and increased neck and arm fat. As well as Cushing’s syndrome, there are a variety of other diseases that may be caused including hypertension, type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular diseases. | |||

==The HPA axis in Relation to Available Fat== | |||

The HPA axis influences the storage and distribution of fat around the body. The situation of fat deposits was compared in pre-menopausal women, and divided into ‘central’ and ‘peripheral’ fat stores. Findings confirmed the relative levels of cortisol influenced the fat distribution, with lower cortisol binding globulin levels leading to increased cortisol and a higher central fat location. The waist-hip ratio of the women was correlated with glucocorticoid effects brought on by increased stress: cortisol production increases most when food is consumed by subjects with ‘central obesity’, rather than ‘peripheral’ fat stores. | |||

Glucocorticoid sensitivity varies between males and females. There are also different interaction levels between the glucocorticoids and the sex steroids. Androgens have agonistic effects with glucocorticoids, while estrogens have antagonistic effects. Females with higher sensitivity to glucocorticoids may develop more central fat adiposity. | |||

Adipose tissues secrete various factors that influence the homeostasis and balance of energy consumption and use. Leptin is secreted in proportion to the available fat stores and can directly inhibit glucocorticoid secretion. The mechanism of the feedback loop involves the HPA axis, and when factors such as stress levels, or overeating occur; the substrates for the mechanism could change- altering the end product. | |||

== The psychology behind the link between stress and eating == | |||

Stress can either cause under- or over-eating. Most people change their eating patterns in stressful situations, and someone who is under extreme pressure at work is more likely to choose to eat food high in sugar and fat, which in the long term could lead to weight gain. Similarly, one study demonstrated that people in a sad state were more inclined to eat high sugar and fat food, whereas people who ate during a happy state were more likely to eat healthier food such as dried fruit. It is also thought that people who are already overweight or obese put on even more weight when they are under stress. | |||

Glucocorticoids play a major role in eating behaviours and also in learning, memory and habit formation. Stress-induced increases in glucocorticoid secretion have an intensifying effect on emotions and motivation and it also appears to increase calorie intake. As glucocorticoids increase, so does insulin secretion. Insulin is thought to have a role in the selection of food, whilst glucocorticoids increase the motivation for choosing a particular food. | |||

There is a relationship between individuals who are feeling stressed before eating and then feeling better after they have eaten highly palatable foods. Infrequent eating of pleasurable foods when under stress will not lead to obesity but eating pleasurable foods more often will develop habits to try to relieve the stress and in the long term this can lead to weight gain and obesity. | |||

==References== | ==References== | ||

{{reflist | 2}}[[Category:Suggestion Bot Tag]] | |||

Latest revision as of 16:01, 22 October 2024

Although stress is often thought of as those social and workplace pressures of modern living that can lead to ill health, stress can be defined as anything that is potentially damaging to the internal homeostasis of an organism. Stressors may be either emotional and physical. Emotional stressors can be anything from a novel environment to potential embarrassment; they involve the perception of the stimuli as being 'stressful' and are processed by the limbic forebrain. On the other hand, physical stressors, esuch as an acute infection or a sudden change in temperature, pose an immediate threat and are processed quickly by the caudal brainstem.

The stress response involves activation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, resulting in heightened vigilance, enhanced cognition and arousal of the autonomic nervous system. These responses help to protect the body and the brain from harmful effects of the stress stimuli. [1]

Activation of the HPA axis triggers a cascade which ultimately leads to the secretion of the glucocorticoid hormone cortisol from the adrenal cortex. Cortisol acts on many cells to influence gene transcription and hence protein synthesis, and it also has direct membrane effects on some cells.

The HPA axis

The HPA axis is comprised of the hypothalamus, the pituitary and the adrenal gland. The hypothalamus is the control centre for most of the hormonal systems in the body. In response to a stressor, be it psychological or physiological, corticotropin-releasing factor (CRF) is secreted. CRF is a peptide hormone which is synthesised by neuroendocrine neurones in the paraventricular nucleus (PVN) of the hypothalamus and released from the median eminence into capillaries that carry it to the pituitary gland (the hypothalamo-hypophysial portal vessels). There, CRF triggers secretion of adrenocorticotrophic hormone (ACTH). In turn, ACTH acts on the adrenal glands to stimulate the production of glucocorticoid hormones, of which cortisol is the main one in humans. Cortisol release triggers negative feedback to the hypothalamus and anterior pituitary, resulting in a fall in circulating ACTH, and subsequently a fall in glucocorticoid production. Cortisol also has metabolic effects which facilitate a return to homeostasis.

Neural mechanisms of appetite control

Several peptides circulating in the blood inform the brain about the body’s nutritional status. Insulin and leptin, (which both suppress appetite) and ghrelin (which induces appetite) all can cross the blood-brain barrier, and one important site of action is at the arcuate nucleus. In the arcuate nucleus, some neurones produce substances which induce feeding (orexigenic) while others produce substances that suppress feeding (anorexigenic). The orexigenic neurons in the arcuate mucleus co-express two neuropeptides: neuropeptide Y (NPY), and Agouti-related peptide (AgRP), and these neurones are inhibited by leptin. Conversely, leptin excitates anorexigenic neurons that express pro-opiomelanocortin (POMC) triggering the release of alpha-MSH, which acts at MC4 receptors to suppress feeding/hunger. AgRP is an inverse agonist at the MC4 receptor, thus increasing NPY/AgRP neurons orexigenic effect [2]

Appetite-regulating neurons of the arcuate nucleus project to many other parts of the hypothalamus, including to the lateral hypothalamus (LH), and the paraventricular nucleus (PVN). PVN stimulation causes inhibition of eating, whilst LH stimulation has the opposite effect. It is in the PVN that the main activator of the HPA axis - corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH) - is synthesised. NPY neurons have abundant projections to the PVN, and due to their close proximity to CRH cell bodies, NPY has a stimulatory effect on CRF release.[3]

The key area of connection between the HPA axis and regulation of feeding is the PVN. Here, the innervation by NPY neurons influences CRF synthesis. CRF inhibits NPY neurones, thus initially CRF is anorexigenic, but glucocorticoids feed back to the brain to inhibit CRF expression. With sustained activation of the HPA axis, there is less CRF inhibition of NPY neurones, resulting in a greater orexigenic drive.[4]

Acute Stress and Appetite

Stress affects every body system and contributes to many contemporary health problems, including obesity.[5]

Stress can be put into two broad categories: acute stress (short term) and chronic stress (stressors occur regulary). We respond to acute stress sometimes by overeating, and sometimes by under-eating, and this may be linked to the particular type of stressor. [6]

HPA Axis – ‘Uncontrollable Stress’

Rodent studies have illustrated a greater caloric intake during the recovery period from a novel stressor. An ‘uncontrollable stressor’ can lead to the activation of the HPA axis resulting in the immediate release of CRH. This stimulates the release of cortisol (corticosterone in rodents). [6] However, it is not known how cortisol triggers over-eating; studies have shown that there is no direct effect of cortisol but it may influence other factors such as leptin, NPY or certain cytokines which have a more direct effect on eating. [7]

Sympathetic-Pituitary-Adrenal Axis – ‘Controllable Stress’

Several studies have shown a suppression of eating in response to acute stress. In certain situations, sometimes termed ‘controllable’ stressors, the ‘Fight or Flight’ response is activated rather than the HPA axis. This mechanism, caused by the release of catecholamines (adrenaline and noradrenaline) from the adrenal glands, causes a range of physiological and behavioural changes to allow the individual to cope with the situation. One such change is a reduction in food intake through a slowed gastric emptying and shunting of the blood vessels to the gastrointestinal tract to allow the muscles an increased blood supply. [6]

Chronic Stress

Chronic stress is the brain’s response to unpleasant events over a long time (more than 24 hours). Examples of chronic stress include job pressures or mental health diseases. While acute stress results in an acute increase in ACTH and glucocorticoid secretion followed by a decrease, chronic stress is associated with a sustained increase in glucocorticoid production, that is associated with a blunting of the normal circadian variation in glucocorticoid production. The effects of chronic stress on the hypothalamus include an inportant change in the CRF neurones of the PVN; these show a markedly increased expression of vasopressin mRNA - their major secretory product changes from being mainly CRF to being mainly vasopressin. Vasopressin, like CRF is a secretagogue for ACTH; on its own it is less potent that CRF, but when vasopressin and CRF are present together they have powerfully synergistic effects on ACTH secretion.

Elsewhere in the brain the chronically elevated glucocorticoids have important effects on the hippocampus, and these are thought to underlie the effects of stress on cognitive function. There is also increased expression of CRF mRNA in the central amygdala, which enables the expression of the “Chronic stress-response network”. This results in an increase in ACTH and therefore corticosterone secretion. There is also an increase in glutamate secretion by the paraventricular nucleus of the thalamus. These structures were identified using c-Fos immunoreactive cells comparisons which were higher for chronically stressed rats than controls.

There are other main effects of chronically high concentration of glucocorticoids [8]. High levels of glucocorticoid activate mechanisms of coping such as increasing the stimulating of pleasurable/compulsive activities such as eating sugary foods and fats. An example of this is the urge to consume “comfort foods”. The combination of “comfort foods”, high insulin levels and high glucocorticoid levels increases abdominal fat depots. This can inhibit CRF mRNA expression in hypothalamic neurons and reduce HPA activity. This increased ingestion of “comfort foods” such as fatty and high sugar content foods and increased abdominal fat are strongly associated with obesity.

Chronic stress can also lead to an overall decrease in the HPA axis’ ability to control hormone levels.

In rats, severe chronic stress results in reduced intake of food. Moderate chronic stress also resultsin reduced food intake. It was shown that as CRF increases, there is a reduction in food ingestion and hence in body weight.

Elevated glucocorticoids of exogenous or endogenous nature for extended periods of time can lead to Cushing’s syndrome. Experiments on rats suggest that the effects of an increase in corticosterone leads to increase in ingestion of foods with high fat and sugar contents. This causes systems such as upper body obesity and increased neck and arm fat. As well as Cushing’s syndrome, there are a variety of other diseases that may be caused including hypertension, type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular diseases.

The HPA axis in Relation to Available Fat

The HPA axis influences the storage and distribution of fat around the body. The situation of fat deposits was compared in pre-menopausal women, and divided into ‘central’ and ‘peripheral’ fat stores. Findings confirmed the relative levels of cortisol influenced the fat distribution, with lower cortisol binding globulin levels leading to increased cortisol and a higher central fat location. The waist-hip ratio of the women was correlated with glucocorticoid effects brought on by increased stress: cortisol production increases most when food is consumed by subjects with ‘central obesity’, rather than ‘peripheral’ fat stores.

Glucocorticoid sensitivity varies between males and females. There are also different interaction levels between the glucocorticoids and the sex steroids. Androgens have agonistic effects with glucocorticoids, while estrogens have antagonistic effects. Females with higher sensitivity to glucocorticoids may develop more central fat adiposity.

Adipose tissues secrete various factors that influence the homeostasis and balance of energy consumption and use. Leptin is secreted in proportion to the available fat stores and can directly inhibit glucocorticoid secretion. The mechanism of the feedback loop involves the HPA axis, and when factors such as stress levels, or overeating occur; the substrates for the mechanism could change- altering the end product.

The psychology behind the link between stress and eating

Stress can either cause under- or over-eating. Most people change their eating patterns in stressful situations, and someone who is under extreme pressure at work is more likely to choose to eat food high in sugar and fat, which in the long term could lead to weight gain. Similarly, one study demonstrated that people in a sad state were more inclined to eat high sugar and fat food, whereas people who ate during a happy state were more likely to eat healthier food such as dried fruit. It is also thought that people who are already overweight or obese put on even more weight when they are under stress.

Glucocorticoids play a major role in eating behaviours and also in learning, memory and habit formation. Stress-induced increases in glucocorticoid secretion have an intensifying effect on emotions and motivation and it also appears to increase calorie intake. As glucocorticoids increase, so does insulin secretion. Insulin is thought to have a role in the selection of food, whilst glucocorticoids increase the motivation for choosing a particular food.

There is a relationship between individuals who are feeling stressed before eating and then feeling better after they have eaten highly palatable foods. Infrequent eating of pleasurable foods when under stress will not lead to obesity but eating pleasurable foods more often will develop habits to try to relieve the stress and in the long term this can lead to weight gain and obesity.

References

- ↑ Habib KE et al. (2001) Neuroendocrinology of stress Endocrinology and Metabolic Clincs of North America 30:695-728 PMID 11571937

- ↑ Schwartz M et al. (2000) Central nervous system control of food intake Nature 404:661-71 PMID 10766253

- ↑ Dimitrov EL et al. (2006) Involvement of neuropeptide Y Y1 receptors in the regulation of neuroendocrine corticotropin-releasing hormone neuronal activity Endocrinology 148:3666-73

- ↑ Cavagnini F et al. (2000) Glucocorticoids and neuroendocrine function Int J Obesity 24: Suppl 2, s77-9 PMID 10997615

- ↑ Habhab S et al. (2009) The relationship between stress, dietary restraint and food preference in women Appetite 52:437-44

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 Torres SJ,Nowson CA (2007) Relationship between stress, eating behaviour and obesity Nutrition 23:887-94

- ↑ Sapolsky R (1998) Why Zebras don't get ulcers; An Updated Guide to Stress, Stress-related Diseases and Coping. Freeman and Co 76-79

- ↑ Dallman MF et al. (2010) Chronic stress and obesity: a new view of ‘comfort food’ Proc Natl Acad Sci 100:11696–701