Linguistics: Difference between revisions

imported>John Stephenson (universal (1st para.)) |

mNo edit summary |

||

| (156 intermediate revisions by 23 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Template: | {{subpages}} | ||

'''Linguistics''' is the [[science|scientific]] study of [[language]]. | [[Image:Spoken-language-naples.jpg|right|thumb|300px|{{#ifexist:Template:Spoken-language-naples.jpg/credit|{{Spoken-language-naples.jpg/credit}}<br/>|}}[[Language]] is arguably what most obviously distinguishes [[human]]s from all other [[species]]. Linguistics involves the study of that system of [[communication]] underlying everyday scenes like this.]] | ||

'''Linguistics''' is the [[science|scientific]] study of [[language]]. Its primary goal is to learn about the [[natural language|'natural' language]] that [[human]]s use every day and how it works. Linguists ask such fundamental questions as: What aspects of language are [[Typological universal|universal]] for all [[human]]s? How can we account for the remarkable [[grammar|grammatical]] similarities between languages as apparently diverse as [[English language|English]], [[Japanese language|Japanese]] and [[Arabic language|Arabic]]? What are the rules of grammar that we language users employ, and how do we come to 'know' them? To what extent is the structure of language related to how we think about the world around us? A ''linguist'', then, here refers to a linguistics expert who seeks to answer such questions, rather than someone who is multilingual. | |||

''[[Theoretical linguistics|Theoretical]]'' linguists are concerned with questions about the apparent human 'instinct' to [[communication|communicate]],<ref>The view that language is an 'instinct' comparable to walking or birdsong is most famously articulated in [[Steven Pinker|Pinker]] (1994).</ref> rather than authorising 'rules' of style or 'correctness' as found in grammar textbooks or popular guides.<ref>A popular recent example is Truss (2003).</ref> For example, *''dog the''<ref>An asterisk (*) indicates that what follows is unacceptable to speakers of that language.</ref> is unacceptable in [[English language|English]], but children recognise as much long before they receive any formal grammatical instruction. It is such recognitions, and the implicit rules they imply, that are of primary concern in linguistics, as opposed to rules as prescribed by an authority. | |||

Although interesting in its own right as one of the directions we follow to learn more about ourselves and the world around us, the study of linguistics is also highly relevant to solving real-life problems. ''[[applied linguistics|Applied]]'' linguists may bring their insights to such fields as [[language education|foreign language teaching]], [[speech therapy]] and [[Translation (language)|translation]].<ref>Increasingly, however, applied linguists have been developing their own views of language, which often focus on the language [[learning|learner]] rather than the system itself: see for example Cook (2002) and the same author's [http://homepage.ntlworld.com/vivian.c/SLA website].</ref> While in [[university|universities]] and research institutions worldwide, scholars are studying the facts of individual languages or the system of language itself to find evidence for [[theory|theories]] or test [[hypothesis|hypotheses]], applied linguists are at work in classrooms, clinics, courts and the highest levels of [[government]]. They use their knowledge to bridge linguistic divides, coax [[speech]] from the mouths of the disabled or [[abuse|abused]], supply [[forensic linguistics|forensic]] evidence in courtroom trials, find out [[language acquisition|how language comes to children]] - in fact, they are everywhere people in need or in conflict over language are to be found. | |||

In virtue of the fact stated in the first paragraph, that the primary goal of linguistics "is to learn about the [[natural language|'natural' language]] that [[human]]s use every day and how it works", we recognize that core areas of linguistics qualify as [[Biology|biological science]], a recognition reinforced by the kinds of questions studiers of linguistics ask and seek answers to, detailed in that first and the succeeding two paragraphs.<ref name=bioling>Di Sciullo AM, Boeckx C. (editors) (2011) ''The Biolinguistic Enterprise: New Perspectives on the Evolution and Nature of the Human Language Faculty''. Oxford: Oxford University Press, ISBN 0199553270. | [http://books.google.com/books?id=aHbNVjpvqU4C&source=gbs_navlinks_s Google Books preview].</ref> | |||

==The study of linguistics== | |||

===Core areas=== | |||

Some linguists, such as theoretical syntacticians, focus on one 'core' area. Research may involve developing a model to describe and predict the workings of the system of language itself, rather than explaining how people happen to use language. These 'core' fields together constitute the [[grammar]] of a language - not a list of rules in a book, but components the system requires for communication. | |||

{{Image|Linguistics-illustration-determinerphrase.gif|right|200px|Levels of linguistic knowledge involved in producing the utterance 'the cats'.}} | |||

====Syntax==== | |||

{{main|Syntax}} | |||

''Syntax'' is the study of how units including [[words]] and [[phrases]] combine into [[sentence]]s. For example, why is ''Bill ate the fish'' acceptable but ''Ate the Bill fish'' not? Syntacticians investigate what orders of words make legitimate sentences, how to succinctly account for patterns found across sentences, such as correspondences between active sentences (''John threw the ball'') and passive sentences (''The ball was thrown by John''), and some types of ambiguity, as in ''Visiting relatives can be boring'' (which has two readings!). | |||

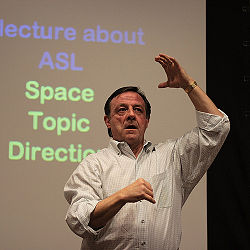

[[Image:Asl-lecture-in-asl.jpg|right|thumb|250px|{{#ifexist:Template:Asl-lecture-in-asl.jpg/credit|{{Spoken-language-naples.jpg/credit}}<br/>|}}A lecture in [[American Sign Language]]. [[Phonology]] and linguistics generally involve the study not just of [[speech]] but also [[sign language]]; the same system used to represent language, whether by sound or sign, is widely viewed as underlying both. Research into sign language also benefits from the insights of linguists who are themselves native signers.]] | |||

====Phonology==== | |||

{{main|Phonology}} | |||

''Phonology'' is the study of the grammatical system speakers use to represent language in the real world, which organises [[syllable]] structure, [[intonation]], [[tone]], and - in [[sign language]]s - [[hand]] movements. A phonologist divides an example of language into its phonological components: for example, English ''cat'' appears as a single syllable arranging the [[phonetic segment|segment]]s [k], [æ]<ref>Pronounced 'ash'.</ref> and [t].<ref>Symbols in square brackets represent speech sounds using the [[International Phonetic Alphabet]]; slanting brackets, as in /kæt/ 'cat', are used to represent [[phoneme]]s - distinct, abstract units that may represent several sounds or written letters.</ref> Although there are potentially infinitely many ways of producing a [[sound]], shaping a [[letter]] or moving a [[hand]], phonologists are interested only in how these group into abstract categories: for example, how and why [k] is often perceived as different from [t], whereas in many languages, other sounds as different as those are not. | |||

====Phonetics==== | |||

{{main|Phonetics}} | |||

''Phonetics'' focuses on the physical sounds of [[speech]]. Phonetics covers [[speech perception]] (how the brain discerns sounds), [[acoustic phonetics|acoustics]] (the physical qualities of sounds as movement through air), and [[articulatory phonetics|articulation]] ([[voice]] production through the movements of the [[lung]]s, [[tongue]], [[lip]]s, and other articulators). This area investigates, for instance, the physical realization of speech and how individual sounds differ across languages and dialects. This research plays a large part in computer [[Speech Recognition|speech recognition]] and synthesis. | |||

====Morphology==== | |||

{{main|Morphology}} | |||

''[[morphology (linguistics)|Morphology]]'' examines how linguistic units such as words and their subparts (such as prefixes and suffixes) combine. One example of this is the observation that while ''walk+ed'' is acceptable, *''ed+walk'' is not, in English, while in other languages such affixes can be found wholly inside the stems they attach to. | |||

==The | ====Semantics==== | ||

{{main|Semantics (linguistics)}} | |||

''Semantics'' within linguistics refers to the study of how language conveys meaning.<ref>The term elsewhere has a rather wider application, referring to the study of meaning itself, in fields such as [[philosophy]].</ref> For example, English speakers typically realise that [[Noam Chomsky|Chomsky]]'s famous sentence ''[[Colorless green ideas sleep furiously]]'' is well-formed in terms of word order, but incomprehensible in terms of meaning.<ref>Chomsky, 1957: 15.</ref> Other aspects of meaning studied here include how speakers understand certain types of [[ambiguous]] sentences such as ''A student met every professor'' (a different student, or the same student?), and the extent to which sentences which are superficially very different, such as ''The wine flowed freely'' and ''Much wine was consumed'', mean similar things.<ref>Aitchison (2003: 87-99).</ref> | |||

====Pragmatics==== | |||

{{main|Pragmatics}} | |||

''Pragmatics'' is the study of how utterances relate to the context they are spoken in. For instance, the sentence ''I have two pencils'' can mean two very different things, depending on whether the speaker has been asked how many pencils he has, in which case the speaker means he has exactly two, or is just confirming that he has at least two (such as in response to ''Can me and my friend borrow two pencils from you?''), leaving open the possibility that he has more. This sort of understanding is not predictable just by knowledge of language; speakers must also know something about the intentions and assumptions of others to [[Cooperative principle|co-operate]] in communication. | |||

===Other fields of linguistics=== | |||

To factor out circumstances that may obscure fundamental insights, many linguists may choose to focus on language as presumed to occur in an idealised, adult, monolingual [[first language acquisition|native speaker]] - prerequisites often found in mainstream [[generative linguistics]].<ref>'Generative' linguistics' is most strongly associated with Chomsky (1957) and subsequent works.</ref> In contrast, linguists whose research moves away from any of these four criteria may concentrate on fields arranged around the study of language use and learning: | |||

* | * [[Biolinguistics]], an interdisciplinary field encompassing and integrating many of the fields below, explores human natural language’s basic properties, development in individuals, use in thinking and communicating, brain implementation, genetic underpinnings, and evolutionary origins.<ref name=bioling>Di Sciullo AM, Boeckx C. (editors) (2011) ''The Biolinguistic Enterprise: New Perspectives on the Evolution and Nature of the Human Language Faculty''. Oxford: Oxford University Press, ISBN 0199553270. | [http://books.google.com/books?id=aHbNVjpvqU4C&source=gbs_navlinks_s Google Books preview].</ref> | ||

* [[ | * [[Language acquisition]], theoretical or applied study of how linguistic knowledge emerges in children and adults as first or subsequent languages, whether naturalistically (without instruction) or in the classroom;<ref>'Acquisition' is a highly diverse field; as well as theoretical linguists studying the linguistic system itself through first language development and [[second language acquisition]] (SLA), applied linguists may examine mainly classroom learning and learners' experiences. Also, language teaching practice is the concern of [[language education|education]] specialists outside linguistics. In any one study linguists' backgrounds and research orientations may overlap considerably, and there is little consensus even on fundamentals, such as the extent to which explicit instruction in presumed 'rules' of grammar can truly promote learning.</ref> | ||

* [[Cognitive linguistics]], the study of language as part of general [[cognition]]; | |||

{{r|Theoretical linguistics}} | |||

* [[Psycholinguistics]], the study of language to find out about how the [[mind]] works;<ref>e.g. Pinker, 1997; Scovel, 1997.</ref> | * [[Psycholinguistics]], the study of language to find out about how the [[mind]] works;<ref>e.g. Pinker, 1997; Scovel, 1997.</ref> | ||

| Line 33: | Line 53: | ||

* [[Sociolinguistics]], the study of how language varies according to cultural context, the speaker's background, and the situation in which it is used; | * [[Sociolinguistics]], the study of how language varies according to cultural context, the speaker's background, and the situation in which it is used; | ||

* [[ | * [[Stylistics (linguistics)|Stylistics]], the study of how language differs according to use and context, e.g. advertising versus speech-making; | ||

* [[Linguistic variation]], the study of the differences among the languages of the world. This has implications for linguistics in general: if human linguistic ability is narrowly constrained, then languages must be very similar. If human linguistic ability is unconstrained, then languages might vary greatly. | |||

* [[Historical linguistics]] (or ''diachronic linguistics''), the study of how languages are historically related (e.g. English, French and [[German language|German]] are thought to be descended from a single [[Indo-European (language)|Indo-European]] tongue). This involves finding [[language universals|universal properties of language]] and accounting for a language's development and origins (see also [[#Historical linguistics|below]] and ''[[comparative linguistics|comparative linguistics]]''). | |||

* [[Contextual linguistics]] may include the study of linguistics in interaction with other academic disciplines. | |||

Contextual linguistics may include the study of linguistics in interaction with other academic disciplines | |||

[[ | * [[Anthropological linguistics]] considers the interactions between linguistics and culture. | ||

[[Critical discourse analysis]] is where [[rhetoric]] and [[philosophy]] interact with linguistics. | * [[Critical discourse analysis]] is where [[rhetoric]] and [[philosophy]] interact with linguistics. | ||

[[ | * [[Computational linguistics]] has had a great influence on theories of syntax and semantics, as modelling syntactic and semantic theories on computers constrains the theories to [[Computability theory (computation)|computable]] operations and provides a more rigorous mathematical basis. | ||

Other cross-disciplinary areas of linguistics include [[ | Other cross-disciplinary areas of linguistics include [[neurolinguistics]], [[evolutionary linguistics]] and [[cognitive science]]. | ||

===Applied linguistics=== | ===Applied linguistics=== | ||

:''Main article: [[Applied linguistics]]'' | |||

Whereas theoretical linguistics is concerned with finding and [[descriptive linguistics|describing]] generalities both within particular languages and among all languages, ''applied linguistics'' takes these results and ''applies'' them to other areas. Often ''applied linguistics'' refers to the use of linguistic research in language teaching, but this is just one sub-discipline: | |||

* Research in [[language teaching]]: today, 'applied linguistics' is sometimes used to refer to 'second language acquisition', but these are distinct fields, in that SLA involves more theoretical study of the system of language, whereas applied linguistics concerns itself more with teaching and learning. In their approach to the study of learning, applied linguists have increasingly devised their own theories and methodologies, such as the shift towards studying the learner rather than the system of language itself, in contrast to the emphasis within SLA.<ref>The applied linguist [[Vivian Cook]] has, for example, introduced the term ''L2 user'' as distinct from ''L2 learner'' (see Cook's page: [http://homepage.ntlworld.com/vivian.c/SLA/Multicompetence/MCopener.htm Background to the L2 User Perspective]). The former are active users of the language; the latter those who learn for later use. Cook's view also severs a link to SLA, in that a user's language ability is seen not as an approximation towards native speakers' competence, but as a system in its own right.</ref><ref>See also Wei (2007) for an appeal to focus on the learner rather than the system.</ref> | |||

* Applied [[computational linguistics]]: two computer applications are [[speech synthesis]] and [[speech recognition]], which use phonetic and phonemic knowledge to provide voice interfaces to computers. [[Machine translation]], [[computer-assisted translation]], and [[natural language processing]] are fruitful areas which have also come to the forefront in recent years. | |||

* [[Clinical linguistics]] entails the application of linguistics to [[speech-language pathology]]. This involves treating individuals whose linguistic development is atypical or impaired.<ref>The most famous case is [[Genie (linguistics)|Genie]], an individual who was deprived of language throughout much of her childhood.</ref> This branch of applied linguistics may also involve treatment of [[specific language impairment]], where one aspect of language develops exceptionally.<ref>Bishop (2006).</ref> The field has also adopted existing ideas which have have not become 'mainstream' in theoretical linguistics. For example, both ''[[behaviourism]]''<ref>Castagnaro (2006), for review.</ref> and ''[[natural phonology]]''<ref>Grunwell (1997).</ref> have appeared in the literature. | |||

=== | ==Approach to studying language== | ||

Modern linguists' methodologies, assumptions and practices differ significantly from those of past generations. One of the most fundamental principles of modern linguistics is that it is [[#Prescription and description|descriptive rather than prescriptive]]: it describes language without judging how people use it. Also, as no language is known to have been written before being spoken, linguists consider [[#Speech versus writing|spoken rather than written language]] to be the primary focus. In language acquisition, most researchers agree that language cannot be acquired through imitation; some aspects must be [[#Innatism|innate]]. Finally, most modern linguistics focuses on language as used today; however, ''[[#Historical linguistics|historical linguistics]]'' remains an important sub-field. | |||

===Prescription and description=== | |||

:''Main article: [[Linguistic prescriptivism]]'' | |||

Linguists seek to clarify the nature of language, to describe how people use it, and to find the underlying grammar that speakers unconsciously adhere to. Linguists do not judge what speech is better or worse syntactically, correct or incorrect grammatically, and do not try to prescribe future language directions. Nonetheless, some professionals and many amateurs do try to ''prescribe'' rules of language, holding a particular standard for all to follow. | |||

Prescription comes in two flavours, those that are linguistically founded and those that are not. For instance, the rule of English that subjects and verbs must ''agree'' (i.e. that when the subject is third-person singular, the verb takes an "s" ending, like "I/you/they run" but "he runs") can be the basis of linguistically founded prescription, so long as the speaker is intending to speak standard American English. Speakers of standard American English ''do'' follow subject-verb agreement, and thus if the intention is to teach that language, this rule should be taught. | |||

However, prescriptivists often stray from this type of linguistically founded recommendation. These prescriptivists tend to be found among the ranks of language educators and journalists, and not in the academic discipline of linguistics. Often considering themselves speakers of the standard form of a particular language, they may hold clear notions of what is right and wrong and what variety of language is most likely to lead the next generation of speakers to 'success'. For example, they may believe that all speakers of what they would call English should follow the same rule of subject-verb agreement, while in fact some varieties of English, which are in a sense distinct languages in their own right, do not do subject-verb agreement the same way. The reasons for their intolerance of non-standard dialects, treating them as "incorrect" , may include distrust of [[neologism]]s, connections to socially-disapproved dialects, or simple conflicts with pet theories. | |||

Prescriptivists often also make linguistically unfounded recommendations that seem plausibly true, but which have little linguistic evidence to support them. For instance, the rule against leaving a preposition at the end of a clause or sentence (such as in ''I met the professor I wrote to'') is commonly believed to be 'correct' English.<ref>Linguists sometimes refer to this rule as ''preposition stranding'', since in ''I met the professor I wrote to'' the preposition's object (''the professor'' in ''I wrote to the professor'') has been left behind once the object has been moved. When a preposition is also moved to a non-final position, as in ''I met the professor to whom I wrote'', this is called [[pied-piping]] or [[wh-movement]], since words that can move can typically be replaced by words beginning with ''wh-'' (''who'', ''what'', etc.).</ref> However, speakers of English not only use final prepositions frequently, indicating that it is perfectly natural English to do so, but bringing the preposition to the front may result in a sentence that could well sound ridiculous to any native speaker of English.<ref>This rule is famously criticised in a quotation attributed to former [[United Kingdom|British]] [[prime minister]] [[Winston Churchill]]: [http://www.wsu.edu/~brians/errors/churchill.html "This is the sort of English up with which I will not put."]</ref> | |||

Descriptive linguists, on the other hand, do not accept the prescriptivists' notion of 'incorrect usage' in a general sense. They aim to describe the usages the prescriptivist has in mind, either as common or deviant from some linguistic norm, as an idiosyncratic variation, or as regularity (a ''rule'') followed by speakers of some other dialect (in contrast to the common prescriptive assumption that "bad" usage is unsystematic). Within the context of [[fieldwork]], [[descriptive linguistics]] refers to the study of language using a descriptivist approach. Descriptivist methodology more closely resembles scientific methodology in other disciplines. | |||

===Speech versus writing=== | |||

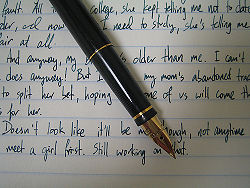

[[Image:Writing-pen-english.jpg|right|thumb|250px|{{#ifexist:Template:Writing-pen-english.jpg/credit|{{Spoken-language-naples.jpg/credit}}<br/>|}}Linguistics examines all forms of language, but the written word is considered at best an incomplete representation of a linguistic system. Linguists generally consider that more fundamental insights can be gleaned into the nature of language by analysing natural, spontaneous speech, rather than assuming the primacy of writing.]] | |||

Languages have only been written for a few thousand years, but have been [[spoken language|spoken]] (or [[sign language|signed]]) for much longer. The [[Written language|written word]] may therefore provide less of a window onto how language works than the study of [[speech]], even assuming that the [[culture]] which the language forms part of has a [[writing system]] - the majority of the world's languages remain unwritten. Furthermore, the study of written language can play no part in investigating [[first language acquisition]], since infants are obviously yet to become literate. Overall, language is held to be an evolutionary adaptation, whereas writing is a comparatively recent invention. Spoken and signed language, then, may tell us much about human evolution and the structure of the [[mind]]. | |||

Of course, linguists also agree that the study of written language can be worthwhile and valuable. For linguistic research that uses the methods of [[corpus linguistics]] and [[computational linguistics]], written language is often much more convenient for processing large amounts of linguistic data. Large corpora of spoken language are difficult to create and hard to find, and are typically [[transcription (linguistics)|transcribed]] and written. Additionally, linguists have turned to text-based discourse occurring in various formats of [[computer-mediated communication]] as a viable site for linguistic inquiry. Writing, however, brings with it a number of problems; for example, it often acts as a historical record, preserving words, phrases, styles and spellings of a previous era. This may be of limited use for studying how language is used at the present time. | |||

===Innatism=== | |||

One of the most interesting aspects of language is that normally, young [[children]] acquire whatever language is spoken (or signed, in the case of [[sign language]]) around them when they are [[maturity|growing up]], without apparently being 'taught' the language. By contrast, other [[animal]]s, even highly intelligent [[primate]]s that are closely related to humans, need very intensive training to produce even minimally language-like behaviour.<ref>Furthermore, the anthropological linguist [[Charles Hockett]] advanced the theory that a collection of ''design features'', such as 'creativity' (speakers can produce novel utterances) collectively made language unique to humans. Some other species may make use of one or two of these (such as 'use of sound signals'), but never enough to use language (Hockett (1960); Aitchison (2003: 13-20). See also the phonetician [http://www.phon.ox.ac.uk/~jcoleman/design_features.htm John Coleman's webpage] comparing different species according to design features.</ref> Additionally, since children understand and produce utterances which they have never previously experienced, and since they appear to reject ill-formed sentences even at an early age,<ref>Chomsky (1957) strongly emphasised that this 'creative' aspect of language entailed that language could not simply be a product of a child's responses to their environment - a view usually associated with [[behaviourism]] and applied to language in Skinner (1957). Chomsky (1959) is a highly critical review of that work that was instrumental in moving linguistics away from such 'behaviourist' analyses of language use.</ref> it has been widely concluded that the infant [[brain]] must in some way be ready to acquire any language. 'Nativist' linguists argue that such a system, presumably specified in our [[gene]]s,<ref>e.g. Pinker (1994) makes an analogy between language and [[spider]]s' [[web]]s: spiders spin webs because their genes compel them to, though without the right environment no webs will appear. To that can be added that each web would be different, though following the same basic, innately guided webspinning template.</ref> must also account for why all languages are fundamentally similar.<ref>The linguist [[Joseph H. Greenberg]] famously identified a series of [[universal]]s of language (Greenberg, 1966); namely, 'laws' that seem to apply to all linguistic communication. One example is that all languages appear to have [[noun]]s and [[verb]]s, even though a language without verbs would be communicatively adequate (e.g. ''[[nominalized English]]'').</ref><ref>Ironically, neither Greenberg nor Hockett, whose work provided such important evidence for the 'nativist' position, themselves supported such a view. Greenberg was a [[typology|typologist]] and [[empirical linguistics|empirical linguist]] interested in [[historical linguistics]] and what the similarities between languages suggested about the nature of language itself; his work has been seen as [[functionalism|functionalist]] in its principles. Hockett was firmly in the pre-Chomskyan [[structuralism|structuralist]] camp, and vigorously attacked the emerging school of generativism throughout his career. See [[William Croft]]'s [http://www.unm.edu/~wcroft/Papers/JHGobit.pdf obituary for Joseph H. Greenberg] and a copy of the ''[[New York Times]]'' obituary for Charles F. Hockett at [http://listserv.linguistlist.org/cgi-bin/wa?A2=ind0011b&L=linganth&P=723 linguistlist.org].</ref> | |||

===Historical linguistics=== | |||

Whereas the core of theoretical linguistics is concerned with studying languages at a particular point in time (usually the present), ''[[historical linguistics]]'' (or ''diachronic linguistics'') examines how language changes through time, sometimes over centuries. Historical linguistics enjoys both a rich history (the study of linguistics grew out of historical linguistics) and a strong theoretical foundation for the study of [[language change]]. | |||

In universities in the USA, the non-historic perspective seems to have the upper hand. Many introductory linguistics classes, for example, cover historical linguistics only cursorily. The shift in focus to a non-historic perspective started with [[Ferdinand de Saussure|Saussure]] and became predominant with [[Noam Chomsky]]. | |||

In [[popular culture]], one aspect of linguistics which is particularly popular is [[etymology]], the study of [[word]] origins. This is related to historical linguistics, in that a word's history is traced over time, but does not form a central component of modern language study; linguistics is more concerned with patterns of change over time and what this has to contribute to an understanding of the nature of language itself. | |||

==History of linguistics== | ==History of linguistics== | ||

{{main|History of linguistics}} | |||

Questions about language, its origins and nature have been a centre of interest in many civilizations.<ref>For example, the early Indian [[grammarian]] {{Unicode|[[Pāṇini]]}}'s (ca 520–460 BCE) examined [[Sanskrit language|Sanskrit]] and produced several insights into the nature of grammar, such as the [[morpheme]], which remain highly relevant in modern research.</ref> From ancient times until the 18th century, insights into language mainly involved explaining the grammar of particular languages, such as [[Sanskrit language|Sanskrit]], or describing changes over time. | |||

Some aspects of modern linguistics can be traced to the [[Swiss people|Swiss]] linguist [[Ferdinand de Saussure]]. He was the first to rigorously define ''language'' and therefore define what linguistics is, and also introduced the idea of language as a ''system'' or ''structure'', which would heavily influence the field. Saussure's work was an early example of how the primary purpose of linguistics became to explain how languages work at one given moment of time and establish how languages work through both [[empirical linguistics|empirical evidence]] and [[theory|theoretical]] reasoning. Elsewhere, a primary concern with describing and preserving the grammars of diverse languages continued well into the twentieth century. | |||

From the 1950s, [[Noam Chomsky]] and his contemporaries initiated new methods in linguistics, producing [[explicit]] theories of grammar<ref>Chomsky (1957); [[The Sound Pattern of English|Chomsky and Halle]] (1968).</ref> - namely, systems that required no reference to other kinds of knowledge. Parallel to this 'Chomskyian' focus on the nature of the linguistic system, concerns about how language was used in society began to mature. In this way, from the 1960s [[William Labov]] was a pioneer in studies of [[sociolinguistics]]. | |||

==Footnotes== | ==Footnotes== | ||

{{reflist|2}}[[Category:Suggestion Bot Tag]] | |||

[[Category: | |||

Latest revision as of 06:01, 12 September 2024

Language is arguably what most obviously distinguishes humans from all other species. Linguistics involves the study of that system of communication underlying everyday scenes like this.

Linguistics is the scientific study of language. Its primary goal is to learn about the 'natural' language that humans use every day and how it works. Linguists ask such fundamental questions as: What aspects of language are universal for all humans? How can we account for the remarkable grammatical similarities between languages as apparently diverse as English, Japanese and Arabic? What are the rules of grammar that we language users employ, and how do we come to 'know' them? To what extent is the structure of language related to how we think about the world around us? A linguist, then, here refers to a linguistics expert who seeks to answer such questions, rather than someone who is multilingual.

Theoretical linguists are concerned with questions about the apparent human 'instinct' to communicate,[1] rather than authorising 'rules' of style or 'correctness' as found in grammar textbooks or popular guides.[2] For example, *dog the[3] is unacceptable in English, but children recognise as much long before they receive any formal grammatical instruction. It is such recognitions, and the implicit rules they imply, that are of primary concern in linguistics, as opposed to rules as prescribed by an authority.

Although interesting in its own right as one of the directions we follow to learn more about ourselves and the world around us, the study of linguistics is also highly relevant to solving real-life problems. Applied linguists may bring their insights to such fields as foreign language teaching, speech therapy and translation.[4] While in universities and research institutions worldwide, scholars are studying the facts of individual languages or the system of language itself to find evidence for theories or test hypotheses, applied linguists are at work in classrooms, clinics, courts and the highest levels of government. They use their knowledge to bridge linguistic divides, coax speech from the mouths of the disabled or abused, supply forensic evidence in courtroom trials, find out how language comes to children - in fact, they are everywhere people in need or in conflict over language are to be found.

In virtue of the fact stated in the first paragraph, that the primary goal of linguistics "is to learn about the 'natural' language that humans use every day and how it works", we recognize that core areas of linguistics qualify as biological science, a recognition reinforced by the kinds of questions studiers of linguistics ask and seek answers to, detailed in that first and the succeeding two paragraphs.[5]

The study of linguistics

Core areas

Some linguists, such as theoretical syntacticians, focus on one 'core' area. Research may involve developing a model to describe and predict the workings of the system of language itself, rather than explaining how people happen to use language. These 'core' fields together constitute the grammar of a language - not a list of rules in a book, but components the system requires for communication.

Syntax

Syntax is the study of how units including words and phrases combine into sentences. For example, why is Bill ate the fish acceptable but Ate the Bill fish not? Syntacticians investigate what orders of words make legitimate sentences, how to succinctly account for patterns found across sentences, such as correspondences between active sentences (John threw the ball) and passive sentences (The ball was thrown by John), and some types of ambiguity, as in Visiting relatives can be boring (which has two readings!).

A lecture in American Sign Language. Phonology and linguistics generally involve the study not just of speech but also sign language; the same system used to represent language, whether by sound or sign, is widely viewed as underlying both. Research into sign language also benefits from the insights of linguists who are themselves native signers.

Phonology

Phonology is the study of the grammatical system speakers use to represent language in the real world, which organises syllable structure, intonation, tone, and - in sign languages - hand movements. A phonologist divides an example of language into its phonological components: for example, English cat appears as a single syllable arranging the segments [k], [æ][6] and [t].[7] Although there are potentially infinitely many ways of producing a sound, shaping a letter or moving a hand, phonologists are interested only in how these group into abstract categories: for example, how and why [k] is often perceived as different from [t], whereas in many languages, other sounds as different as those are not.

Phonetics

Phonetics focuses on the physical sounds of speech. Phonetics covers speech perception (how the brain discerns sounds), acoustics (the physical qualities of sounds as movement through air), and articulation (voice production through the movements of the lungs, tongue, lips, and other articulators). This area investigates, for instance, the physical realization of speech and how individual sounds differ across languages and dialects. This research plays a large part in computer speech recognition and synthesis.

Morphology

Morphology examines how linguistic units such as words and their subparts (such as prefixes and suffixes) combine. One example of this is the observation that while walk+ed is acceptable, *ed+walk is not, in English, while in other languages such affixes can be found wholly inside the stems they attach to.

Semantics

Semantics within linguistics refers to the study of how language conveys meaning.[8] For example, English speakers typically realise that Chomsky's famous sentence Colorless green ideas sleep furiously is well-formed in terms of word order, but incomprehensible in terms of meaning.[9] Other aspects of meaning studied here include how speakers understand certain types of ambiguous sentences such as A student met every professor (a different student, or the same student?), and the extent to which sentences which are superficially very different, such as The wine flowed freely and Much wine was consumed, mean similar things.[10]

Pragmatics

Pragmatics is the study of how utterances relate to the context they are spoken in. For instance, the sentence I have two pencils can mean two very different things, depending on whether the speaker has been asked how many pencils he has, in which case the speaker means he has exactly two, or is just confirming that he has at least two (such as in response to Can me and my friend borrow two pencils from you?), leaving open the possibility that he has more. This sort of understanding is not predictable just by knowledge of language; speakers must also know something about the intentions and assumptions of others to co-operate in communication.

Other fields of linguistics

To factor out circumstances that may obscure fundamental insights, many linguists may choose to focus on language as presumed to occur in an idealised, adult, monolingual native speaker - prerequisites often found in mainstream generative linguistics.[11] In contrast, linguists whose research moves away from any of these four criteria may concentrate on fields arranged around the study of language use and learning:

- Biolinguistics, an interdisciplinary field encompassing and integrating many of the fields below, explores human natural language’s basic properties, development in individuals, use in thinking and communicating, brain implementation, genetic underpinnings, and evolutionary origins.[5]

- Language acquisition, theoretical or applied study of how linguistic knowledge emerges in children and adults as first or subsequent languages, whether naturalistically (without instruction) or in the classroom;[12]

- Cognitive linguistics, the study of language as part of general cognition;

- Theoretical linguistics [r]: Core field of linguistics, which attempts to establish the characteristics of the system of language itself by postulating models of linguistic competence common to all humans. [e]

- Psycholinguistics, the study of language to find out about how the mind works;[13]

- Sociolinguistics, the study of how language varies according to cultural context, the speaker's background, and the situation in which it is used;

- Stylistics, the study of how language differs according to use and context, e.g. advertising versus speech-making;

- Linguistic variation, the study of the differences among the languages of the world. This has implications for linguistics in general: if human linguistic ability is narrowly constrained, then languages must be very similar. If human linguistic ability is unconstrained, then languages might vary greatly.

- Historical linguistics (or diachronic linguistics), the study of how languages are historically related (e.g. English, French and German are thought to be descended from a single Indo-European tongue). This involves finding universal properties of language and accounting for a language's development and origins (see also below and comparative linguistics).

- Contextual linguistics may include the study of linguistics in interaction with other academic disciplines.

- Anthropological linguistics considers the interactions between linguistics and culture.

- Critical discourse analysis is where rhetoric and philosophy interact with linguistics.

- Computational linguistics has had a great influence on theories of syntax and semantics, as modelling syntactic and semantic theories on computers constrains the theories to computable operations and provides a more rigorous mathematical basis.

Other cross-disciplinary areas of linguistics include neurolinguistics, evolutionary linguistics and cognitive science.

Applied linguistics

- Main article: Applied linguistics

Whereas theoretical linguistics is concerned with finding and describing generalities both within particular languages and among all languages, applied linguistics takes these results and applies them to other areas. Often applied linguistics refers to the use of linguistic research in language teaching, but this is just one sub-discipline:

- Research in language teaching: today, 'applied linguistics' is sometimes used to refer to 'second language acquisition', but these are distinct fields, in that SLA involves more theoretical study of the system of language, whereas applied linguistics concerns itself more with teaching and learning. In their approach to the study of learning, applied linguists have increasingly devised their own theories and methodologies, such as the shift towards studying the learner rather than the system of language itself, in contrast to the emphasis within SLA.[14][15]

- Applied computational linguistics: two computer applications are speech synthesis and speech recognition, which use phonetic and phonemic knowledge to provide voice interfaces to computers. Machine translation, computer-assisted translation, and natural language processing are fruitful areas which have also come to the forefront in recent years.

- Clinical linguistics entails the application of linguistics to speech-language pathology. This involves treating individuals whose linguistic development is atypical or impaired.[16] This branch of applied linguistics may also involve treatment of specific language impairment, where one aspect of language develops exceptionally.[17] The field has also adopted existing ideas which have have not become 'mainstream' in theoretical linguistics. For example, both behaviourism[18] and natural phonology[19] have appeared in the literature.

Approach to studying language

Modern linguists' methodologies, assumptions and practices differ significantly from those of past generations. One of the most fundamental principles of modern linguistics is that it is descriptive rather than prescriptive: it describes language without judging how people use it. Also, as no language is known to have been written before being spoken, linguists consider spoken rather than written language to be the primary focus. In language acquisition, most researchers agree that language cannot be acquired through imitation; some aspects must be innate. Finally, most modern linguistics focuses on language as used today; however, historical linguistics remains an important sub-field.

Prescription and description

- Main article: Linguistic prescriptivism

Linguists seek to clarify the nature of language, to describe how people use it, and to find the underlying grammar that speakers unconsciously adhere to. Linguists do not judge what speech is better or worse syntactically, correct or incorrect grammatically, and do not try to prescribe future language directions. Nonetheless, some professionals and many amateurs do try to prescribe rules of language, holding a particular standard for all to follow.

Prescription comes in two flavours, those that are linguistically founded and those that are not. For instance, the rule of English that subjects and verbs must agree (i.e. that when the subject is third-person singular, the verb takes an "s" ending, like "I/you/they run" but "he runs") can be the basis of linguistically founded prescription, so long as the speaker is intending to speak standard American English. Speakers of standard American English do follow subject-verb agreement, and thus if the intention is to teach that language, this rule should be taught.

However, prescriptivists often stray from this type of linguistically founded recommendation. These prescriptivists tend to be found among the ranks of language educators and journalists, and not in the academic discipline of linguistics. Often considering themselves speakers of the standard form of a particular language, they may hold clear notions of what is right and wrong and what variety of language is most likely to lead the next generation of speakers to 'success'. For example, they may believe that all speakers of what they would call English should follow the same rule of subject-verb agreement, while in fact some varieties of English, which are in a sense distinct languages in their own right, do not do subject-verb agreement the same way. The reasons for their intolerance of non-standard dialects, treating them as "incorrect" , may include distrust of neologisms, connections to socially-disapproved dialects, or simple conflicts with pet theories.

Prescriptivists often also make linguistically unfounded recommendations that seem plausibly true, but which have little linguistic evidence to support them. For instance, the rule against leaving a preposition at the end of a clause or sentence (such as in I met the professor I wrote to) is commonly believed to be 'correct' English.[20] However, speakers of English not only use final prepositions frequently, indicating that it is perfectly natural English to do so, but bringing the preposition to the front may result in a sentence that could well sound ridiculous to any native speaker of English.[21]

Descriptive linguists, on the other hand, do not accept the prescriptivists' notion of 'incorrect usage' in a general sense. They aim to describe the usages the prescriptivist has in mind, either as common or deviant from some linguistic norm, as an idiosyncratic variation, or as regularity (a rule) followed by speakers of some other dialect (in contrast to the common prescriptive assumption that "bad" usage is unsystematic). Within the context of fieldwork, descriptive linguistics refers to the study of language using a descriptivist approach. Descriptivist methodology more closely resembles scientific methodology in other disciplines.

Speech versus writing

Linguistics examines all forms of language, but the written word is considered at best an incomplete representation of a linguistic system. Linguists generally consider that more fundamental insights can be gleaned into the nature of language by analysing natural, spontaneous speech, rather than assuming the primacy of writing.

Languages have only been written for a few thousand years, but have been spoken (or signed) for much longer. The written word may therefore provide less of a window onto how language works than the study of speech, even assuming that the culture which the language forms part of has a writing system - the majority of the world's languages remain unwritten. Furthermore, the study of written language can play no part in investigating first language acquisition, since infants are obviously yet to become literate. Overall, language is held to be an evolutionary adaptation, whereas writing is a comparatively recent invention. Spoken and signed language, then, may tell us much about human evolution and the structure of the mind.

Of course, linguists also agree that the study of written language can be worthwhile and valuable. For linguistic research that uses the methods of corpus linguistics and computational linguistics, written language is often much more convenient for processing large amounts of linguistic data. Large corpora of spoken language are difficult to create and hard to find, and are typically transcribed and written. Additionally, linguists have turned to text-based discourse occurring in various formats of computer-mediated communication as a viable site for linguistic inquiry. Writing, however, brings with it a number of problems; for example, it often acts as a historical record, preserving words, phrases, styles and spellings of a previous era. This may be of limited use for studying how language is used at the present time.

Innatism

One of the most interesting aspects of language is that normally, young children acquire whatever language is spoken (or signed, in the case of sign language) around them when they are growing up, without apparently being 'taught' the language. By contrast, other animals, even highly intelligent primates that are closely related to humans, need very intensive training to produce even minimally language-like behaviour.[22] Additionally, since children understand and produce utterances which they have never previously experienced, and since they appear to reject ill-formed sentences even at an early age,[23] it has been widely concluded that the infant brain must in some way be ready to acquire any language. 'Nativist' linguists argue that such a system, presumably specified in our genes,[24] must also account for why all languages are fundamentally similar.[25][26]

Historical linguistics

Whereas the core of theoretical linguistics is concerned with studying languages at a particular point in time (usually the present), historical linguistics (or diachronic linguistics) examines how language changes through time, sometimes over centuries. Historical linguistics enjoys both a rich history (the study of linguistics grew out of historical linguistics) and a strong theoretical foundation for the study of language change.

In universities in the USA, the non-historic perspective seems to have the upper hand. Many introductory linguistics classes, for example, cover historical linguistics only cursorily. The shift in focus to a non-historic perspective started with Saussure and became predominant with Noam Chomsky.

In popular culture, one aspect of linguistics which is particularly popular is etymology, the study of word origins. This is related to historical linguistics, in that a word's history is traced over time, but does not form a central component of modern language study; linguistics is more concerned with patterns of change over time and what this has to contribute to an understanding of the nature of language itself.

History of linguistics

Questions about language, its origins and nature have been a centre of interest in many civilizations.[27] From ancient times until the 18th century, insights into language mainly involved explaining the grammar of particular languages, such as Sanskrit, or describing changes over time.

Some aspects of modern linguistics can be traced to the Swiss linguist Ferdinand de Saussure. He was the first to rigorously define language and therefore define what linguistics is, and also introduced the idea of language as a system or structure, which would heavily influence the field. Saussure's work was an early example of how the primary purpose of linguistics became to explain how languages work at one given moment of time and establish how languages work through both empirical evidence and theoretical reasoning. Elsewhere, a primary concern with describing and preserving the grammars of diverse languages continued well into the twentieth century.

From the 1950s, Noam Chomsky and his contemporaries initiated new methods in linguistics, producing explicit theories of grammar[28] - namely, systems that required no reference to other kinds of knowledge. Parallel to this 'Chomskyian' focus on the nature of the linguistic system, concerns about how language was used in society began to mature. In this way, from the 1960s William Labov was a pioneer in studies of sociolinguistics.

Footnotes

- ↑ The view that language is an 'instinct' comparable to walking or birdsong is most famously articulated in Pinker (1994).

- ↑ A popular recent example is Truss (2003).

- ↑ An asterisk (*) indicates that what follows is unacceptable to speakers of that language.

- ↑ Increasingly, however, applied linguists have been developing their own views of language, which often focus on the language learner rather than the system itself: see for example Cook (2002) and the same author's website.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Di Sciullo AM, Boeckx C. (editors) (2011) The Biolinguistic Enterprise: New Perspectives on the Evolution and Nature of the Human Language Faculty. Oxford: Oxford University Press, ISBN 0199553270. | Google Books preview.

- ↑ Pronounced 'ash'.

- ↑ Symbols in square brackets represent speech sounds using the International Phonetic Alphabet; slanting brackets, as in /kæt/ 'cat', are used to represent phonemes - distinct, abstract units that may represent several sounds or written letters.

- ↑ The term elsewhere has a rather wider application, referring to the study of meaning itself, in fields such as philosophy.

- ↑ Chomsky, 1957: 15.

- ↑ Aitchison (2003: 87-99).

- ↑ 'Generative' linguistics' is most strongly associated with Chomsky (1957) and subsequent works.

- ↑ 'Acquisition' is a highly diverse field; as well as theoretical linguists studying the linguistic system itself through first language development and second language acquisition (SLA), applied linguists may examine mainly classroom learning and learners' experiences. Also, language teaching practice is the concern of education specialists outside linguistics. In any one study linguists' backgrounds and research orientations may overlap considerably, and there is little consensus even on fundamentals, such as the extent to which explicit instruction in presumed 'rules' of grammar can truly promote learning.

- ↑ e.g. Pinker, 1997; Scovel, 1997.

- ↑ The applied linguist Vivian Cook has, for example, introduced the term L2 user as distinct from L2 learner (see Cook's page: Background to the L2 User Perspective). The former are active users of the language; the latter those who learn for later use. Cook's view also severs a link to SLA, in that a user's language ability is seen not as an approximation towards native speakers' competence, but as a system in its own right.

- ↑ See also Wei (2007) for an appeal to focus on the learner rather than the system.

- ↑ The most famous case is Genie, an individual who was deprived of language throughout much of her childhood.

- ↑ Bishop (2006).

- ↑ Castagnaro (2006), for review.

- ↑ Grunwell (1997).

- ↑ Linguists sometimes refer to this rule as preposition stranding, since in I met the professor I wrote to the preposition's object (the professor in I wrote to the professor) has been left behind once the object has been moved. When a preposition is also moved to a non-final position, as in I met the professor to whom I wrote, this is called pied-piping or wh-movement, since words that can move can typically be replaced by words beginning with wh- (who, what, etc.).

- ↑ This rule is famously criticised in a quotation attributed to former British prime minister Winston Churchill: "This is the sort of English up with which I will not put."

- ↑ Furthermore, the anthropological linguist Charles Hockett advanced the theory that a collection of design features, such as 'creativity' (speakers can produce novel utterances) collectively made language unique to humans. Some other species may make use of one or two of these (such as 'use of sound signals'), but never enough to use language (Hockett (1960); Aitchison (2003: 13-20). See also the phonetician John Coleman's webpage comparing different species according to design features.

- ↑ Chomsky (1957) strongly emphasised that this 'creative' aspect of language entailed that language could not simply be a product of a child's responses to their environment - a view usually associated with behaviourism and applied to language in Skinner (1957). Chomsky (1959) is a highly critical review of that work that was instrumental in moving linguistics away from such 'behaviourist' analyses of language use.

- ↑ e.g. Pinker (1994) makes an analogy between language and spiders' webs: spiders spin webs because their genes compel them to, though without the right environment no webs will appear. To that can be added that each web would be different, though following the same basic, innately guided webspinning template.

- ↑ The linguist Joseph H. Greenberg famously identified a series of universals of language (Greenberg, 1966); namely, 'laws' that seem to apply to all linguistic communication. One example is that all languages appear to have nouns and verbs, even though a language without verbs would be communicatively adequate (e.g. nominalized English).

- ↑ Ironically, neither Greenberg nor Hockett, whose work provided such important evidence for the 'nativist' position, themselves supported such a view. Greenberg was a typologist and empirical linguist interested in historical linguistics and what the similarities between languages suggested about the nature of language itself; his work has been seen as functionalist in its principles. Hockett was firmly in the pre-Chomskyan structuralist camp, and vigorously attacked the emerging school of generativism throughout his career. See William Croft's obituary for Joseph H. Greenberg and a copy of the New York Times obituary for Charles F. Hockett at linguistlist.org.

- ↑ For example, the early Indian grammarian Pāṇini's (ca 520–460 BCE) examined Sanskrit and produced several insights into the nature of grammar, such as the morpheme, which remain highly relevant in modern research.

- ↑ Chomsky (1957); Chomsky and Halle (1968).