Dallas, Texas: Difference between revisions

imported>Richard Jensen (add bibliog) |

mNo edit summary |

||

| (18 intermediate revisions by 6 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

'''Dallas''' is a major city, county, and metropolitan area in northeastern Texas; the city population in 2006 was 1,250,180. The county population was 2,346,000 in 2000. The Dallas–Fort Worth–Arlington metropolitan area reached 6,145,000 million in 2007 after achieving the largest numeric gain of any metro area in the U.S. between 2006 and 2007, increasing by 162,250. Only New York, Los Angeles and Chicago metro areas were larger, while Houston came next after Dallas. | {{subpages}} | ||

{{dambigbox|Dallas, Texas|Dallas}} | |||

'''Dallas''' is a major city, county, and metropolitan area in northeastern [[Texas (U.S. state)|Texas]]; the city population in 2006 was 1,250,180. The county population was 2,346,000 in 2000. The Dallas–Fort Worth–Arlington metropolitan area reached 6,145,000 million in 2007 after achieving the largest numeric gain of any metro area in the U.S. between 2006 and 2007, increasing by 162,250. Only [[New York (disambiguation)|New York]], [[Los Angeles, California|Los Angeles]] and [[Chicago, Illinois]] metro areas were larger, while [[Houston]] came next after Dallas. | |||

Dallas is home to one of the twelve district [[Federal Reserve System]] banks. | |||

==History== | ==History== | ||

In 1841, two years after his first visit to stake a claim to the land on which Dallas now stands, John Neely Bryan, a Tennessee trader, returned to the then [[Republic of Texas]] and built a tiny one-room cabin, the first in Dallas. Ir remains one of the few historical landmarks preserved in the city, and has been moved to the front of the Dallas County Courthouse. Bryan, quick to see the advantages of the National Highway then being built toward his land, founded a village. In 1844 the village was laid out in lots 200 feet square. The | In 1841, two years after his first visit to stake a claim to the land on which Dallas now stands, [[John Neely Bryan]], a Tennessee trader, returned to the then [[Republic of Texas]] and built a tiny one-room cabin, the first in Dallas. Ir remains one of the few historical landmarks preserved in the city <ref>Architect James Pratt, however has suggested that the current cabin is actually a 1930s reproduction. See [http://www.wfaa.com/sharedcontent/dws/wfaa/latestnews/stories/wfaa070419_lj_mojo.25283f2e.html report]</ref>, and has been moved to the front of the Dallas County Courthouse. Bryan, quick to see the advantages of the National Highway then being built toward his land, founded a village. In 1844 the village was laid out in lots 200 feet square. The origin of the name is unclear but Dallas County in 1846 was named after George Mifflin Dallas, the current vice-president of the United States. | ||

Dallas was incorporated as a town in 1856 and became an important regional trading center. In 1856 several hundred Europeans, followers of the French social philosopher [[Charles Fourier]], attempted to set up a socialistic colony called "La Réunion" across the river from Dallas. The colony failed in 1858, and many of the colonists moved to Dallas, bringing with them a cosmopolitanism then lacking in most of the state. | |||

The town, almost completely destroyed by fire in July 1860, was rebuilt during the 1860s. Phillips (1999) explores the economic, political, ethnic, and regional tensions that caused an outbreak of mass white hysteria in response to an alleged slave rebellion that was held responsible for the great fire. Three slaves were hanged, and two Iowa preachers were whipped and run out of town, hounded by frantic locals led by editor Charles R. Pryor of the ''Dallas Herald''. | |||

During the [[American Civil War|Civil War]], Dallas was the quartermaster, commissary, and administrative headquarters for the Confederate Army, but no fighting occurred near the city. In [[Reconstruction]] many freedmen (ex slaves) resettled in camps on the periphery of the city. By 1870 the population reached 3,000. | |||

[[Image:Dallas1879.jpg|thumb|300px|Dallas in 1879]] | |||

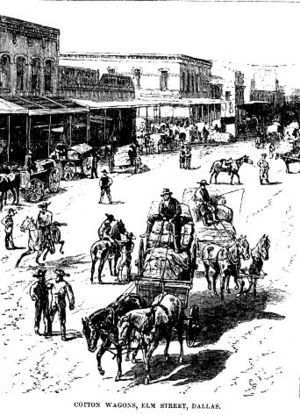

Dallas was incorporated as a city in 1871 and grew rapidly during the 1870s as a railroad and distribution center for northeast Texas. In 1873, through a trick played on the legislature, the east-west Texas and Pacific Railroad was persuaded to cross at Dallas the tracks of the Houston and Texas railroad, which was being built northward from the Gulf. The Houston and Texas Central railroad (arriving in 1872) and the Texas and Pacific (arriving in 1873) made Dallas the main rail crossroads in Texas. Its strategic geographical location made it the transportation center for shipping local regional products to northern and eastern factories. Cotton became the region's principal cash crop, and Elm Street in Dallas was its market. The city became the world center for the leather and buffalo-hide trade. Wholesale houses opened to distribute manufactured products to the small towns in the region. The boom years brought on by the railroad in the 1870s greatly accelerated the growth of Dallas while exacerbating class and ethnic stratification among the city's population, which reached 10,400 in 1880. The telephone arrived in 1881, and electricity (for office buildings) in 1882. Each sign of progress, big or small, was trumpeted by the boosterism of the daily press, notably the ''Dallas Morning News'' (begun 1885) and the ''Dallas Times Herald'' (begun 1888). Church membership grew rapidly and the city became well known across the South, especially among Baptists, in theology and religious affairs. | |||

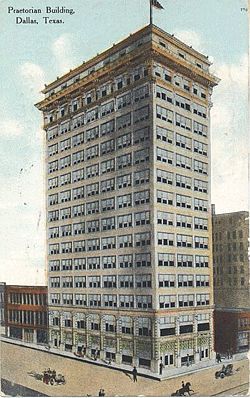

[[Image:Dallas- | By 1900 the city's population reached 38,000 as banking and insurance became major activities in the increasingly white-collar city, which was now the world's leading cotton center. Businessmen took control of civic affairs; with little municipal patronage, there was only a small role for the Democratic party to play (and no role for the predominantly black Republican party.) A dramatic sign of progress was the towering 190-foot steel-frame skyscraper--the fourteen-story Praetorian Building, built in 1909 to house the Praetorian insurance company. Dallas became the regional headquarters of the Federal Reserve in 1914, strengthening its dominance of Texas banking. | ||

[[Image:Dallas-Praetorian.jpg|thumb|250px]] | |||

Growth accelerated, hitting 260,000 at the onset of the [[Great Depression, U.S.|Great Depression]] in 1929. The city suffered less than others because it had relatively little manufacturing, apart from a Ford auto plant. Cotton formers, facing very low prices in 1930-33, purchased a lot less, but the [[New Deal]] farm programs restored prices. New Deal relief programs, especially the [[CCC]] and [[WPA]] provided jobs for the unemployed, while major civic construction projects were funded by other New Deal agencies. | |||

===Progressive era: 1890-1930=== | ===Progressive era: 1890-1930=== | ||

[[Progressive Era]] reformers sought to improve municipal government by such changes as the commission system, city planning, and zoning controls. The interests of white business and residential districts were protected, but sometimes at the expense of blacks who lived in segregated neighborhoods.<ref>Patricia E. Gower, "The Price of Exclusion: Dallas Municipal Policy and its Impact on African Americans." ''East Texas Historical Journal'' 2001 39(1): 43-54. Issn: 0424-1444 </ref> Fairbanks (1999) explores the changing assumptions about city planning and government among the city's leaders. Dissatisfied with its haphazard development they endorsed centralized planning and wrote and secured the adoption of a new charter and set up a board of commissioners. The commission structure, however, caused government officials to view the city in separate parts rather than as a whole. By the 1920s supporters of comprehensive planning were calling for a program that included adoption of council-manager government, a citywide zoning policy, and public funds for improvements in parks, sewers, schools, and city streets. Voters approved the bond proposals and charter amendments in 1927 and 1930. Dallas thus achieved a more coordinated government which was theoretically more aware of the city's needs and more able to treat those needs equally for the benefit of the city as a whole. | [[Progressive Era]] reformers sought to improve municipal government by such changes as the commission system, city planning, and zoning controls. The interests of white business and residential districts were protected, but sometimes at the expense of blacks who lived in segregated neighborhoods.<ref>Patricia E. Gower, "The Price of Exclusion: Dallas Municipal Policy and its Impact on African Americans." ''East Texas Historical Journal'' 2001 39(1): 43-54. Issn: 0424-1444 </ref> Fairbanks (1999) explores the changing assumptions about city planning and government among the city's leaders. Dissatisfied with its haphazard development they endorsed centralized planning and wrote and secured the adoption of a new charter and set up a board of commissioners. The commission structure, however, caused government officials to view the city in separate parts rather than as a whole. By the 1920s supporters of comprehensive planning were calling for a program that included adoption of council-manager government, a citywide zoning policy, and public funds for improvements in parks, sewers, schools, and city streets. Voters approved the bond proposals and charter amendments in 1927 and 1930. Dallas thus achieved a more coordinated government which was theoretically more aware of the city's needs and more able to treat those needs equally for the benefit of the city as a whole. | ||

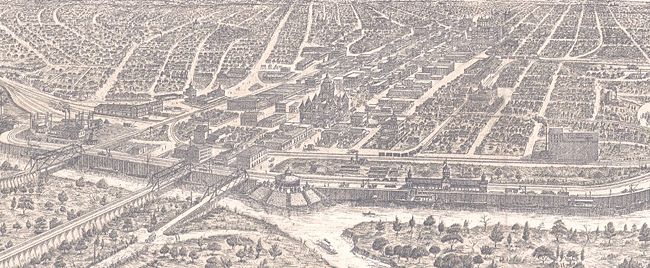

[[Image:Tx-dallas-1892.jpg|thumb|650px|downtown Dallas in 1892]] | |||

==Self image== | ==Self image== | ||

The city's fathers originally depicted Dallas as southern in order to rationalize slavery and opposition to [[Reconstruction]], but this discouraged Northern investment and the political support of wealthy | The city's fathers originally depicted Dallas as southern in order to rationalize slavery and opposition to [[Reconstruction]], but this discouraged Northern investment and the political support of wealthy northern migrants to the city. From the 1870s on, Dallas leaders portrayed the city as southwestern, or later as part of the "Sunbelt", in order to incorporate wealthy non-southern whites, including Jews, into society. For example, between 1852 and 1925 the seven Sanger brothers built successful mercantile businesses along developing railroad lines, including the Sanger Bros. department store, and occupied numerous city and state government posts.<ref>Rose G. Biderman, "The Sanger Brothers and Their Role in Texas History." ''Western States Jewish History'' 1996 28(2): 149-158. Issn: 0749-5471 </ref> White blue collar workers were marginalized, and even more so the Mexican Americans, and blacks.<ref> See Michael Phillips, ''White Metropolis: Race, Ethnicity, and Religion in Dallas, 1841-2001.'' (2006). </ref> | ||

==Gender== | ==Gender== | ||

Women did much to establish the fundamental elements of the social structure of the city, focusing their energies on families, schools, and churches during the city's pioneer days. Many of the organizations which created a modern urban scene were founded and led by middle class women. Through voluntary organizations and club work, they connected their city to national cultural and social trends. By the 1880s women in temperance and suffrage movements shifted the boundaries between private and public life in Dallas by pushing their way into politics in the name of social issues.<ref> Elizabeth York Enstam, ''Women and the Creation of Urban Life: Dallas, Texas, 1843-1920.'' (1998). </ref> | Women did much to establish the fundamental elements of the social structure of the city, focusing their energies on families, schools, and churches during the city's pioneer days. Many of the organizations which created a modern urban scene were founded and led by middle class women. Through voluntary organizations and club work, they connected their city to national cultural and social trends. By the 1880s women in temperance and suffrage movements shifted the boundaries between private and public life in Dallas by pushing their way into politics in the name of social issues.<ref> Elizabeth York Enstam, ''Women and the Creation of Urban Life: Dallas, Texas, 1843-1920.'' (1998). </ref> | ||

| Line 25: | Line 35: | ||

Women of color usually operated separately. Juanita Craft (1902-85) was a leader in the civil rights movement through the Dallas NAACP. She focused on working with black youths, organizing them as the vanguard in protests against segregation practices in Texas.<ref> Stefanie Decker, "Women in the Civil Rights Movement: Juanita Craft Versus the Dallas Elite." ''East Texas Historical Journal'' 2001 39(1): 33-42. Issn: 0424-1444 </ref> | Women of color usually operated separately. Juanita Craft (1902-85) was a leader in the civil rights movement through the Dallas NAACP. She focused on working with black youths, organizing them as the vanguard in protests against segregation practices in Texas.<ref> Stefanie Decker, "Women in the Civil Rights Movement: Juanita Craft Versus the Dallas Elite." ''East Texas Historical Journal'' 2001 39(1): 33-42. Issn: 0424-1444 </ref> | ||

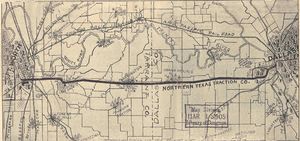

[[Image:Dallas-1905rr.jpg|thumb|650ppx|Dallas-Ft. Worth area in 1905; the solid line is the inter-urban trolley]] | |||

== | ==Footnotes== | ||

{{reflist|2}}[[Category:Suggestion Bot Tag]] | |||

[[Category: | |||

Latest revision as of 11:00, 4 August 2024

Dallas is a major city, county, and metropolitan area in northeastern Texas; the city population in 2006 was 1,250,180. The county population was 2,346,000 in 2000. The Dallas–Fort Worth–Arlington metropolitan area reached 6,145,000 million in 2007 after achieving the largest numeric gain of any metro area in the U.S. between 2006 and 2007, increasing by 162,250. Only New York, Los Angeles and Chicago, Illinois metro areas were larger, while Houston came next after Dallas.

Dallas is home to one of the twelve district Federal Reserve System banks.

History

In 1841, two years after his first visit to stake a claim to the land on which Dallas now stands, John Neely Bryan, a Tennessee trader, returned to the then Republic of Texas and built a tiny one-room cabin, the first in Dallas. Ir remains one of the few historical landmarks preserved in the city [1], and has been moved to the front of the Dallas County Courthouse. Bryan, quick to see the advantages of the National Highway then being built toward his land, founded a village. In 1844 the village was laid out in lots 200 feet square. The origin of the name is unclear but Dallas County in 1846 was named after George Mifflin Dallas, the current vice-president of the United States.

Dallas was incorporated as a town in 1856 and became an important regional trading center. In 1856 several hundred Europeans, followers of the French social philosopher Charles Fourier, attempted to set up a socialistic colony called "La Réunion" across the river from Dallas. The colony failed in 1858, and many of the colonists moved to Dallas, bringing with them a cosmopolitanism then lacking in most of the state.

The town, almost completely destroyed by fire in July 1860, was rebuilt during the 1860s. Phillips (1999) explores the economic, political, ethnic, and regional tensions that caused an outbreak of mass white hysteria in response to an alleged slave rebellion that was held responsible for the great fire. Three slaves were hanged, and two Iowa preachers were whipped and run out of town, hounded by frantic locals led by editor Charles R. Pryor of the Dallas Herald.

During the Civil War, Dallas was the quartermaster, commissary, and administrative headquarters for the Confederate Army, but no fighting occurred near the city. In Reconstruction many freedmen (ex slaves) resettled in camps on the periphery of the city. By 1870 the population reached 3,000.

Dallas was incorporated as a city in 1871 and grew rapidly during the 1870s as a railroad and distribution center for northeast Texas. In 1873, through a trick played on the legislature, the east-west Texas and Pacific Railroad was persuaded to cross at Dallas the tracks of the Houston and Texas railroad, which was being built northward from the Gulf. The Houston and Texas Central railroad (arriving in 1872) and the Texas and Pacific (arriving in 1873) made Dallas the main rail crossroads in Texas. Its strategic geographical location made it the transportation center for shipping local regional products to northern and eastern factories. Cotton became the region's principal cash crop, and Elm Street in Dallas was its market. The city became the world center for the leather and buffalo-hide trade. Wholesale houses opened to distribute manufactured products to the small towns in the region. The boom years brought on by the railroad in the 1870s greatly accelerated the growth of Dallas while exacerbating class and ethnic stratification among the city's population, which reached 10,400 in 1880. The telephone arrived in 1881, and electricity (for office buildings) in 1882. Each sign of progress, big or small, was trumpeted by the boosterism of the daily press, notably the Dallas Morning News (begun 1885) and the Dallas Times Herald (begun 1888). Church membership grew rapidly and the city became well known across the South, especially among Baptists, in theology and religious affairs.

By 1900 the city's population reached 38,000 as banking and insurance became major activities in the increasingly white-collar city, which was now the world's leading cotton center. Businessmen took control of civic affairs; with little municipal patronage, there was only a small role for the Democratic party to play (and no role for the predominantly black Republican party.) A dramatic sign of progress was the towering 190-foot steel-frame skyscraper--the fourteen-story Praetorian Building, built in 1909 to house the Praetorian insurance company. Dallas became the regional headquarters of the Federal Reserve in 1914, strengthening its dominance of Texas banking.

Growth accelerated, hitting 260,000 at the onset of the Great Depression in 1929. The city suffered less than others because it had relatively little manufacturing, apart from a Ford auto plant. Cotton formers, facing very low prices in 1930-33, purchased a lot less, but the New Deal farm programs restored prices. New Deal relief programs, especially the CCC and WPA provided jobs for the unemployed, while major civic construction projects were funded by other New Deal agencies.

Progressive era: 1890-1930

Progressive Era reformers sought to improve municipal government by such changes as the commission system, city planning, and zoning controls. The interests of white business and residential districts were protected, but sometimes at the expense of blacks who lived in segregated neighborhoods.[2] Fairbanks (1999) explores the changing assumptions about city planning and government among the city's leaders. Dissatisfied with its haphazard development they endorsed centralized planning and wrote and secured the adoption of a new charter and set up a board of commissioners. The commission structure, however, caused government officials to view the city in separate parts rather than as a whole. By the 1920s supporters of comprehensive planning were calling for a program that included adoption of council-manager government, a citywide zoning policy, and public funds for improvements in parks, sewers, schools, and city streets. Voters approved the bond proposals and charter amendments in 1927 and 1930. Dallas thus achieved a more coordinated government which was theoretically more aware of the city's needs and more able to treat those needs equally for the benefit of the city as a whole.

Self image

The city's fathers originally depicted Dallas as southern in order to rationalize slavery and opposition to Reconstruction, but this discouraged Northern investment and the political support of wealthy northern migrants to the city. From the 1870s on, Dallas leaders portrayed the city as southwestern, or later as part of the "Sunbelt", in order to incorporate wealthy non-southern whites, including Jews, into society. For example, between 1852 and 1925 the seven Sanger brothers built successful mercantile businesses along developing railroad lines, including the Sanger Bros. department store, and occupied numerous city and state government posts.[3] White blue collar workers were marginalized, and even more so the Mexican Americans, and blacks.[4]

Gender

Women did much to establish the fundamental elements of the social structure of the city, focusing their energies on families, schools, and churches during the city's pioneer days. Many of the organizations which created a modern urban scene were founded and led by middle class women. Through voluntary organizations and club work, they connected their city to national cultural and social trends. By the 1880s women in temperance and suffrage movements shifted the boundaries between private and public life in Dallas by pushing their way into politics in the name of social issues.[5]

During 1913-19, advocates of woman suffrage drew on the educational and advertising techniques of the national parties and the lobbying tactics of the women's club movement. They also tapped into popular culture, successfully using popular symbolism and traditional ideals to adapt community festivals and social gatherings to the task of political persuasion. The Dallas Equal Suffrage Association developed a suffrage campaign based on social values and community standards. Community and social occasions served as recruiting opportunities for the suffrage cause, blunting its radical implications with the familiarity of customary events and dressing it in the values of traditional female behavior, especially propriety.[6]

Women of color usually operated separately. Juanita Craft (1902-85) was a leader in the civil rights movement through the Dallas NAACP. She focused on working with black youths, organizing them as the vanguard in protests against segregation practices in Texas.[7]

Footnotes

- ↑ Architect James Pratt, however has suggested that the current cabin is actually a 1930s reproduction. See report

- ↑ Patricia E. Gower, "The Price of Exclusion: Dallas Municipal Policy and its Impact on African Americans." East Texas Historical Journal 2001 39(1): 43-54. Issn: 0424-1444

- ↑ Rose G. Biderman, "The Sanger Brothers and Their Role in Texas History." Western States Jewish History 1996 28(2): 149-158. Issn: 0749-5471

- ↑ See Michael Phillips, White Metropolis: Race, Ethnicity, and Religion in Dallas, 1841-2001. (2006).

- ↑ Elizabeth York Enstam, Women and the Creation of Urban Life: Dallas, Texas, 1843-1920. (1998).

- ↑ Elizabeth York Enstam, "The Dallas Equal Suffrage Association, Political Style, and Popular Culture: Grassroots Strategies of the Woman Suffrage Movement, 1913-1919." Journal of Southern History 2002 68(4): 817-848.

- ↑ Stefanie Decker, "Women in the Civil Rights Movement: Juanita Craft Versus the Dallas Elite." East Texas Historical Journal 2001 39(1): 33-42. Issn: 0424-1444