User:Aleksander Stos/ComplexNumberAdvanced: Difference between revisions

imported>Aleksander Stos (essentials) |

No edit summary |

||

| (36 intermediate revisions by 2 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

''This is an experimental draft. For a brief description of | {{AccountNotLive}} | ||

''This is an experimental draft. For a brief description of this project click [[User_talk:Jitse Niesen#Essentials|here.]]'' | |||

__TOC__ | |||

==Definition== | |||

Complex numbers are defined as ordered pairs of reals: | Complex numbers are defined as ordered pairs of reals: | ||

:<math>\mathbb{C}= \{ (a,b) \colon a,b\in \mathbb{R} \}.</math> | :<math>\mathbb{C}= \{ (a,b) \colon a,b\in \mathbb{R} \}.</math> | ||

| Line 6: | Line 9: | ||

*addition: <math>(a, b) + (c, d) = (a + c, b + d)</math> | *addition: <math>(a, b) + (c, d) = (a + c, b + d)</math> | ||

*multiplication: <math>(a, b)(c, d) = (ac - bd, bc + ad)</math> | *multiplication: <math>(a, b)(c, d) = (ac - bd, bc + ad)</math> | ||

<math>\scriptstyle \mathbb{C}</math> with the addition and | <math>\scriptstyle \mathbb{C}</math> with the addition and multiplication is the [[field (mathematics) | field]] of complex numbers. From another of view, <math>\scriptstyle \mathbb{C} </math> with complex additions and multiplication by ''real'' numbers is a 2-dimesional [[vector space]]. | ||

To perform basic computations it is convenient to introduce the ''imaginary unit'', ''i''=(0,1).<ref>in some applications it is denoted by ''j'' as well.</ref> | To perform basic computations it is convenient to identify numbers of the form <math>\{ (a,0):\;\;a\in\mathbb{R} \}</math> with the usual real line <math>(\mathbb{R})</math> and to introduce the ''imaginary unit'', ''i''=(0,1).<ref>in some applications it is denoted by ''j'' as well.</ref> The imaginary unit has the fundamental property <math>\scriptstyle i^2=-1.</math> Indeed, <math>(0,1)\cdot(0,1) = (-1,0) = -1.</math> | ||

Any complex number <math>z=(a,b)</math> can be written as <math>z=a+bi</math> (this is often called the ''algebraic form'') and vice-versa. | Any complex number <math>z=(a,b)</math> can be written as <math>z=a+bi</math> (this is often called the ''algebraic form'') and vice-versa. The numbers ''a'' and ''b'' are called the ''real part'' and the ''imaginary part'' of ''z'', respectively. We denote <math>a=\Re (z)</math> and <math>b=\Im (z).</math> Remark that two complex numbers are equal if and only if their real and complex part are equal, respectively. Notice that ''i'' makes the multiplication quite natural: | ||

:<math>(a + bi)(c + di) = (ac - bd) + (bc + ad)i. </math> | :<math>(a + bi)(c + di) = (ac - bd) + (bc + ad)i. </math> | ||

We define the ''modulus'' of ''z'', denoted by <math>|z|</math>, | |||

:<math>|z|=\sqrt{a^2+b^2}.</math> | :<math>|z|=\sqrt{a^2+b^2}.</math> | ||

We have for any two complex numbers <math>z_1</math> and <math>z_2</math> | We have for any two complex numbers <math>z_1</math> and <math>z_2</math> | ||

* <math> |\bar z| = |z|;</math> | |||

* <math>|z_1\cdot z_2| = |z_1| \cdot |z_2|;</math> | * <math>|z_1\cdot z_2| = |z_1| \cdot |z_2|;</math> | ||

* <math>|\frac{z_1}{ z_2}| = \frac{|z_1|}{|z_2|},</math> provided <math>z_2\not =0.</math> | * <math>|\frac{z_1}{ z_2}| = \frac{|z_1|}{|z_2|},</math> provided <math>z_2\not =0.</math> | ||

| Line 22: | Line 24: | ||

For <math>z=a+bi</math> we define also <math>\bar z</math>, the ''conjugate'', by <math>\bar z= a-bi.</math> Then we have | For <math>z=a+bi</math> we define also <math>\bar z</math>, the ''conjugate'', by <math>\bar z= a-bi.</math> Then we have | ||

* <math> \bar{(\bar z)} = z</math> | |||

* <math>\bar z_1 \pm \bar z_2 = \overline{(z_1 \pm z_2)};</math> | * <math>\bar z_1 \pm \bar z_2 = \overline{(z_1 \pm z_2)};</math> | ||

* <math> \bar z_1 \cdot \bar z_2 = \overline{(z_1\cdot z_2)};</math> | * <math> \bar z_1 \cdot \bar z_2 = \overline{(z_1\cdot z_2)};</math> | ||

* <math>\overline{\left( \frac{z_1}{z_2} \right)} = \frac{\bar z_1}{\bar z_2},</math> provided <math>z_2\not =0;</math> | * <math>\overline{\left( \frac{z_1}{z_2} \right)} = \frac{\bar z_1}{\bar z_2},</math> provided <math>z_2\not =0;</math> | ||

* <math>z\bar z = |z|^2.</math> | * <math>z\bar z = |z|^2.</math> | ||

==Geometric interpretation== | |||

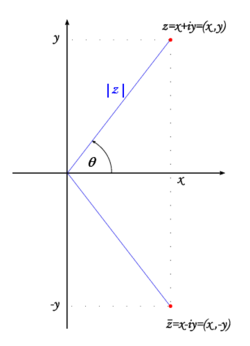

Complex numbers may be naturally represented on the ''complex plane'', where <math>z=x+iy</math> corresponds to the point (''x'',''y''), see the fig. 1. | |||

{{Image|Complex_plane3.png|right|250px|Fig. 1. Graphical representation of a complex number and its conjugate}} | |||

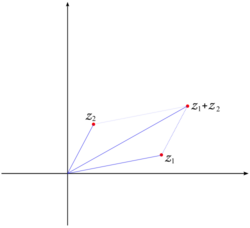

The modulus is just the distance from the point <math>z=(x,y)</math> and the origin. More generally, <math>|z_1-z_2|</math> is the distance between the two given points. Furthermore, the conjugation is just the symmetry with respect to the x-axis. The sum of two given complex numbers <math>z_1</math> and <math>z_2</math> can be geometrically determined as a vertex of a parallelogram determined by the points 0, <math>z_1</math> and <math>z_2</math> (i.e. the fourth vertex given these three, see the fig. 2). {{Image|Complex_sum_2.png|right|250px|Fig. 2. Graphical representation of the sum of two complex numbers}} | |||

==Trigonometric and exponential form== | |||

As the graphical representation suggests, any complex number ''z=a+bi'' of modulus 1 (i.e. a point from the unit circle) can be written as <math>z=\cos \theta + i\sin\theta</math> | |||

for some <math>\theta\in [0,2\pi).</math> So actually any (non-null) <math>z\in\mathbb{C}</math> can be represented as | |||

:<math>z=r(\cos\theta + i\sin \theta),</math> where ''r'' traditionally stands for |''z''|. | |||

This is the ''trigonometric form'' of the complex number ''z''. If we adopt convention that <math>\theta \in [0,2\pi)</math> then such <math>\theta</math> is unique and called the ''argument'' of ''z''.<ref>In literature the convention <math>\theta\in (-\pi,\pi]</math> is found as well.</ref> | |||

The equality of two complex numbers <math>z_1=r_1e^{i\theta_1}</math> and <math>z_2=r_2e^{i\theta_2}</math> is equivalent to <math>r_1=r_2</math> and <math>\theta_1=\theta_2+2k\pi</math> for certain integer ''k''. | |||

Graphically, the number <math>\theta</math> is the (oriented) angle between the ''x''-axis and the interval containing 0 and ''z''. | |||

Closely related is the ''exponential notation''. Let us define the complex exponential as | |||

:<math>e^z = \sum_0^\infty \frac{z^n}{n!}.</math> | |||

The sum is convergent for any <math>z\in\mathbb{C}</math> and by a comparison with the series of <math>\sin z </math> and <math>\cos z</math> it may be seen that | |||

:<math>(*) \quad \quad e^{i\theta}=\cos\theta + i\sin\theta,\quad\quad \theta\in\mathbb{R}. </math> | |||

This is known as Euler's formula. As a particular example we get | |||

:<math> e^{i\pi}=-1.</math> | |||

In turn, the Euler's formula may be used to determine <math>\cos \theta</math> and <math>\sin \theta</math>: | |||

:<math>\cos \theta = \Re(e^{i\theta}) = \frac{e^{i\theta}+e^{-i\theta}}{2},</math> | |||

:<math>\sin \theta = \Im (e^{i\theta}) = \frac{e^{i\theta}-e^{-i\theta}}{2i}.</math> | |||

In fact, these formulas are valid not only for <math>\theta\in \mathbb{R}</math> but also for any <math>z\in\mathbb{C}.</math> | |||

Another consequence is that any (non-zero) <math>z\in \mathbb{C}</math> can be written as | |||

:<math> z= r e^{i\theta}</math> with the same ''r'' and <math>\theta</math> as above. | |||

This is called the ''exponential form'' of the complex number ''z''.<ref>The equivalence of two complex numbers can be checked as in the trigonometric form case.</ref> | |||

It is well-adapted to perform multiplications. Indeed, for any <math>z_1=r_1e^{i\theta_1}</math> and <math>z_2=r_2e^{i\theta_2}</math> we have | |||

* <math>z_1 z_2= r_1r_2 e^{i(\theta_1+\theta_2)}</math> | |||

* <math>\frac{z_1}{z_2} = \frac{r_1}{r_2} e^{i(\theta_1-\theta_2)},</math> provided <math>z_2\not=0.</math> | |||

The following particular case of complex multiplication is well-know as the [[de Moivre]]'s formula | |||

<ref>It is commonly used to ''linearise'' powers of trigonometric functions in integrals.</ref> | |||

:<math> (cos\theta+i\sin\theta)^n = \cos(n\theta)+i\sin(n\theta)</math> | |||

{{Image|Graphical_multiplication1.png|right|200px|Fig 3. Multiplication by <math>i</math> amounts to rotation by 90 degrees.}} | |||

Graphically, multiplication by a constant complex number <math>z=re^{i\theta}</math> amounts to the rotation by <math>\theta</math> and the [[homothety]] of ratio ''r''. In particular, the multiplication by ''i'' amounts to the rotation by the right angle (counter-clockwise), see Fig. 3. | |||

==Complex roots== | |||

Any non-constant [[polynomial]] with complex coefficients has a complex root. This result is known as the [[Fundamental Theorem of Algebra]]. Consequently, any complex polynomial of degree ''n'' has exactly ''n'' roots (counted with multiplicities). In particular, the equation | |||

:<math>z^n=a</math>, | |||

where ''z'' is the variable and ''a'' a non-zero constant has exactly ''n'' solutions. They are called ''n''<sup>th</sup> (complex) ''roots'' of ''a''. If ''a'' is written in the exponential form, <math>a=re^{i\theta},</math> then the ''n'' roots of ''a'', denoted as <math>z_0,z_2,\ldots,z_{n-1}</math>, are given by | |||

:<math> z_k = \sqrt[n]{r}\cdot\exp\left (i \left(\frac{\theta+2k\pi}{n}\right)\right),\quad k=0,1,\ldots,n-1. </math> | |||

{{Image|Complex_roots.png|right|300px|5th roots of unity}} | |||

One may observe that | |||

:<math> z_{k} = z_{k-1}e^{i\theta/n};</math> or, equivalently, <math> z_{k} = z_0 e^{ik\theta/n},\quad k=1,2,\ldots,n-1.</math> | |||

Since that multiplication by the exponential <math>e^{i\theta/n}</math> represents a rotation by <math>\theta/n</math>, the above formula interpreted geometrically means that the roots form a regular n-sided polygon centred at the origin; the vertices of the polygon belong to the circle of radius <math>\sqrt[n]{r}.</math> (see fig. 4). | |||

Particularly important are the roots of unity, i.e. solutions of <math>z^n=1</math>. | |||

The cubic roots of 1 (with n=3) are | |||

:<math> 1,\, -\frac{1}{2}+i\frac{\sqrt{3}}{2},\, -\frac{1}{2}-i\frac{\sqrt{3}}{2} </math> | |||

and for n=4 we have | |||

:<math> \frac{1}{2}+\frac{\sqrt{2}}{2},\, \frac{1}{2}-\frac{\sqrt{2}}{2},\, \frac{1}{2}+\frac{\sqrt{2}}{2},\, -\frac{1}{2}-\frac{\sqrt{2}}{2}. </math> | |||

See also the fig.4 for the 5th roots of unity. | |||

==Notes== | |||

{{reflist}} | |||

Latest revision as of 02:19, 22 November 2023

The account of this former contributor was not re-activated after the server upgrade of March 2022.

This is an experimental draft. For a brief description of this project click here.

Definition

Complex numbers are defined as ordered pairs of reals:

Such pairs can be added and multiplied as follows

- addition:

- multiplication:

with the addition and multiplication is the field of complex numbers. From another of view, with complex additions and multiplication by real numbers is a 2-dimesional vector space.

To perform basic computations it is convenient to identify numbers of the form with the usual real line and to introduce the imaginary unit, i=(0,1).[1] The imaginary unit has the fundamental property Indeed, Any complex number can be written as (this is often called the algebraic form) and vice-versa. The numbers a and b are called the real part and the imaginary part of z, respectively. We denote and Remark that two complex numbers are equal if and only if their real and complex part are equal, respectively. Notice that i makes the multiplication quite natural:

We define the modulus of z, denoted by ,

We have for any two complex numbers and

- provided

For we define also , the conjugate, by Then we have

- provided

Geometric interpretation

Complex numbers may be naturally represented on the complex plane, where corresponds to the point (x,y), see the fig. 1.

The modulus is just the distance from the point and the origin. More generally, is the distance between the two given points. Furthermore, the conjugation is just the symmetry with respect to the x-axis. The sum of two given complex numbers and can be geometrically determined as a vertex of a parallelogram determined by the points 0, and (i.e. the fourth vertex given these three, see the fig. 2).

Trigonometric and exponential form

As the graphical representation suggests, any complex number z=a+bi of modulus 1 (i.e. a point from the unit circle) can be written as for some So actually any (non-null) can be represented as

- where r traditionally stands for |z|.

This is the trigonometric form of the complex number z. If we adopt convention that then such is unique and called the argument of z.[2] The equality of two complex numbers and is equivalent to and for certain integer k. Graphically, the number is the (oriented) angle between the x-axis and the interval containing 0 and z.

Closely related is the exponential notation. Let us define the complex exponential as

The sum is convergent for any and by a comparison with the series of and it may be seen that

This is known as Euler's formula. As a particular example we get

In turn, the Euler's formula may be used to determine and :

In fact, these formulas are valid not only for but also for any

Another consequence is that any (non-zero) can be written as

- with the same r and as above.

This is called the exponential form of the complex number z.[3] It is well-adapted to perform multiplications. Indeed, for any and we have

- provided

The following particular case of complex multiplication is well-know as the de Moivre's formula [4]

Graphically, multiplication by a constant complex number amounts to the rotation by and the homothety of ratio r. In particular, the multiplication by i amounts to the rotation by the right angle (counter-clockwise), see Fig. 3.

Complex roots

Any non-constant polynomial with complex coefficients has a complex root. This result is known as the Fundamental Theorem of Algebra. Consequently, any complex polynomial of degree n has exactly n roots (counted with multiplicities). In particular, the equation

- ,

where z is the variable and a a non-zero constant has exactly n solutions. They are called nth (complex) roots of a. If a is written in the exponential form, then the n roots of a, denoted as , are given by

One may observe that

- or, equivalently,

Since that multiplication by the exponential represents a rotation by , the above formula interpreted geometrically means that the roots form a regular n-sided polygon centred at the origin; the vertices of the polygon belong to the circle of radius (see fig. 4).

Particularly important are the roots of unity, i.e. solutions of . The cubic roots of 1 (with n=3) are

and for n=4 we have

See also the fig.4 for the 5th roots of unity.

![{\displaystyle z_{k}={\sqrt[{n}]{r}}\cdot \exp \left(i\left({\frac {\theta +2k\pi }{n}}\right)\right),\quad k=0,1,\ldots ,n-1.}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/4de2e8dda63702b0f37f89ed1f61da356f793b41)

![{\displaystyle {\sqrt[{n}]{r}}.}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/60047449bb022b61c61fe017ff256f9d17f33e32)

![{\displaystyle \theta \in (-\pi ,\pi ]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/2742d923047f035ec3e8db8259485fda0629104b)