Alexander Hamilton: Difference between revisions

imported>Ryan Weicker |

mNo edit summary |

||

| (4 intermediate revisions by 2 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{subpages}} | {{subpages}} | ||

{{TOC|right}} | {{TOC|right}} | ||

'''Alexander Hamilton''' (1757-1804) was an American politician, | '''Alexander Hamilton''' (1757-1804) was an American politician, military officer, and political theorist who helped garner support for the [[United States Constitution]] with his contributions to the ''[[Federalist Papers]]''. As the first Secretary of the Treasury (1789-1795), he created the financial infrastructure and policy of the new government and helped found the first modern political party, the [[Federalist Party]], in 1792. Hamilton called for a strong national government to protect the United States from foreign enemies and to promote industry, finance, commerce and economic modernization. His chief adversary was [[Thomas Jefferson]], who favored state sovereignty and an agricultural-based society. The nation's first party system organized itself around their competing visions for the new republic beginning in 1792. | ||

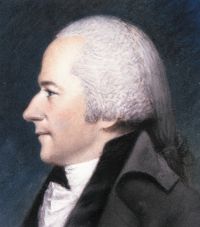

[[Image:Secretary of the Treasury Hamilton.jpg|300px|left|frame|Secretary of the Treasury Hamilton by James Sharples, 1796.]] | [[Image:Secretary of the Treasury Hamilton.jpg|300px|left|frame|Secretary of the Treasury Hamilton by James Sharples, 1796.]] | ||

Hamilton's greatest achievements came | Hamilton's greatest achievements came between 1788 and 1793, when he authored over fifty articles supporting ratification of the Constitution in the ''Federalist Papers'' (coauthored with [[James Madison]] and [[John Jay]]) and built a solid, permanent financial base for the nation, using the national debt, tariffs and taxes, and a national bank. The stability encouraged the rapid growth of a stable financial system. He tried to advance the cause of manufacturing, but had few results. His hostility to President [[John Adams]] over the latter's policy of neutrality weakened the Federalist party, which was permanently displaced in 1800. Hamilton's last great action was to secure the election of Jefferson as president in 1801 over the dangerous [[Aaron Burr]]. Vice-President Burr killed Hamilton in a duel in 1804. | ||

Hamilton remains one of the most controversial in American historiography. Historians continue to ask, "Was he a closet monarchist or a sincere republican? A victim of partisan politics or one of its most active promoters? A lackey for British interests or a foreign policy mastermind? An economic genius or a shill for special interests? The father of a vigorous national government or the destroyer of genuine federalism? A defender of governmental authority or a dangerous militarist?"<ref>Ambrose and Martin, ed. ''The Many Faces of Alexander Hamilton'' (2006) p. 11 </ref> | |||

==Early Career== | ==Early Career== | ||

| Line 42: | Line 42: | ||

Hamilton found his own bride, Elizabeth Schulyer, daughter of General Philip Schuyler. She met all his criteria and their marriage in 1780 allied Hamilton with one of the richest and most powerful families of New York state. They had ten children.<ref> Chernow, ch 7</ref> | Hamilton found his own bride, Elizabeth Schulyer, daughter of General Philip Schuyler. She met all his criteria and their marriage in 1780 allied Hamilton with one of the richest and most powerful families of New York state. They had ten children.<ref> Chernow, ch 7</ref> | ||

== | ==Notes== | ||

<references/> | <references/> | ||

--------- | ---------[[Category:Suggestion Bot Tag]] | ||

Latest revision as of 06:01, 8 July 2024

Alexander Hamilton (1757-1804) was an American politician, military officer, and political theorist who helped garner support for the United States Constitution with his contributions to the Federalist Papers. As the first Secretary of the Treasury (1789-1795), he created the financial infrastructure and policy of the new government and helped found the first modern political party, the Federalist Party, in 1792. Hamilton called for a strong national government to protect the United States from foreign enemies and to promote industry, finance, commerce and economic modernization. His chief adversary was Thomas Jefferson, who favored state sovereignty and an agricultural-based society. The nation's first party system organized itself around their competing visions for the new republic beginning in 1792.

Hamilton's greatest achievements came between 1788 and 1793, when he authored over fifty articles supporting ratification of the Constitution in the Federalist Papers (coauthored with James Madison and John Jay) and built a solid, permanent financial base for the nation, using the national debt, tariffs and taxes, and a national bank. The stability encouraged the rapid growth of a stable financial system. He tried to advance the cause of manufacturing, but had few results. His hostility to President John Adams over the latter's policy of neutrality weakened the Federalist party, which was permanently displaced in 1800. Hamilton's last great action was to secure the election of Jefferson as president in 1801 over the dangerous Aaron Burr. Vice-President Burr killed Hamilton in a duel in 1804.

Hamilton remains one of the most controversial in American historiography. Historians continue to ask, "Was he a closet monarchist or a sincere republican? A victim of partisan politics or one of its most active promoters? A lackey for British interests or a foreign policy mastermind? An economic genius or a shill for special interests? The father of a vigorous national government or the destroyer of genuine federalism? A defender of governmental authority or a dangerous militarist?"[1]

Early Career

Hamilton was born on Jan. 11, 1757 (or 1755) on the small British colony of Nevis, in the Caribbean. He was the illegitimate son of a Scottish merchant; his mother the daughter of a French Huguenot physician and planter. The father had deserted, and the mother died in 1768, leaving Hamilton and his brother orphaned. He was sent to the nearby island of St. Croix. He was a self-taught prodigy who impressed the businessmen and ministers there. As a teenager he had managed an important business when the owner was away; his astonishingly precocious account of a hurricane that swept the island[2] convinced the leaders to set up a fund to send him to America. He had some preliminary training at a grammar school in New Jersey, where he became friends with William Livingston and his circle of patriots, including his lifelong friend John Jay. Hamilton in 1773 entered King's College (renamed Columbia College, now part of Columbia University).

Revolution

Hamilton quickly emerged as a leader of the patriots in New York City. At a mass meeting on July 6, 1774, he spoke against British measures, and at once began writing anonymously for the newspapers with a style and brilliance which attracted attention. In December 1774, he wrote "A Full Vindication of the Measures of Congress from the Calumnies of Their Enemies," in some 14,000 words.[3] When the Tory intellectual leader Rev. Dr. Samuel Seabury replied, Hamilton retorted with "The Farmer Refuted; or, a More Comprehensive and Impartial View of the Disputes Between Great Britain and the Colonies," which ran some 35,000 words. Hamilton's anonymous pamphlets displayed a keen grasp of the issues, extensive knowledge of British and American government, and such rhetorical power that they were attributed to senior patriots, not a teenager. Hamilton at this point was a moderate who still acknowledged the King's sovereignty and the British connection but rejected the rule of Parliament.

As the revolutionary movement escalated so did Hamilton's involvement. He formed a volunteer militia company after the fighting broke out in 1775 and in early 1776 he was appointed captain of a new artillery company set up by New York. His skill in drilling his company attracted the attention of generals. The war moved to New York in late summer 1776 and Hamilton fought with Washington at battles at Long Island and White Plains, and was in the retreat. Washington spotted Hamilton's talent and made him a secretary, and aide-de-camp, with the rank of lieutenant-colonel. He wrote most of Washington's routine letters and orders, and was entrusted with missions to senior generals. Washington, however, always made the decisions. Hamilton became a trusted advisor and virtual chief of staff.[4]

Hamilton was an analytical problem solver; he examined issues in depth and presented a bold solution. At the nerve center of the war effort, he realized the new nation's strengths and weaknesses. His report of Jan. 28, 1778 proposed a reorganization of the army[5]; his report of May 5, 1778, improved the efficiency of the Army's inspector-general's office (his plan was adopted by Congress). Hamilton drafted a comprehensive set of military regulations for Washington. In correspondence with nationally minded leaders in several states he demonstrated his form belief in representative government, rather than rule by elites. He argued the supposed instability of democracies was because most had really been "compound governments," with a partitioned authority; Hamilton declared that "a representative democracy, where the right of election is well secured and regulated, & the exercise of the legislative, executive, and judiciary authorities, is vested in select persons, chosen really and not nominally by the people, will, in my opinion, be most likely to be happy, regular, and durable."[6]. Hamilton insisted from the first that his democracy should have a highly centralized authority, armed with powers for every emergency. By 1780 he concluded the Articles of Confederation made for a hopelessly weak nation that could not feed, clothe or pay its soldiers. Hamilton never had a high regard for state rights; he wanted Congress to have "complete sovereignty in all that relates to war, peace, trade, finance."

New Constitution

Treasury Years

National debt

Hamilton's first major triumph was the assumption of the state debts by the national government in 1790, over the objections of Jefferson and Hamilton.[7] They worked a compromise whereby the South would get the national capital. Proposed by Hamilton as a way to manage the debt incurred from the Revolution and tie the interests of rich men in every state to the fututre of the nation as a whole, the Funding Act became the basis for federal borrowing, debt repayment, and governmental financing; ity polarized politicsd and hastened the formation of parties. Madison argued that federal control of debt would consolidate too much power in the hands of the federal government, a sentiment shared by Jefferson, though he initially backed the plan. After its passage in 1790, however, all parties left the plan in place, despite earlier objections, and allowed the federal government to pay off its debt by mortgaging its tax revenue through loans. This system of loans with slow repayment by relatively low taxes restored the credit of the United States to foreign lien holders and stimulated the economy of the early republic, allowing the federal government to take out loans to finance the War of 1812 and purchase land from Spain in 1819.[8]

Hamilton is also one of two men that are featured on US currency that was not the President of the United States. He is currently pictured on the ten dollar bill.

Federalist politics: 1795-1804

As the founder of the Federalist party, Hamilton supported it with subsidies to newspaper editors like Noah Webster, and the encouragement of the Treasury's network of friends and supporters. After he left the Treasury he tried to keep control, with less success. He disliked John Adams and tried to block his election in 1796. When Adams was elected he kept Washington's entire cabinet, which was secretly beholden to Hamilton.

Hamilton's philosophy

Martin (2005) examines Hamilton's evolving ideas about republicanism in the face of harsh criticism throughout the political battles of the 1790s. Hamilton conceived a theory of virtue and republican citizenship in the context of the prevailing competing visions that emphasized either "confidence" or "vigilance" from its citizens. His new theory was formulated out of legal issues involving press liberty and ultimately led to a belief in the need for public confidence to legitimate a government that was both responsible and vigorous.

The S.U.M. fiasco

The Society for Establishing Useful Manufactures (S.U.M.) was a Hamilton's brainstorm to demonstrate the new nation could achieve independence of European imports by its own factories on a much larger scale than the small operations then in existence. He envisioned a capital of one millions dollars for factories that would produce paper, sailcloth, linen, cotton cloth, shoes, thread, stockings, pottery, ribbons, carpets, brass and iron ware. Hamilton declared, there was "a moral certainty of success." The site was Paterson, New Jersey, with an ample hard-working labor supply, near major ports, with abundant water power, and rich in minerals. A charter granted in 1791 by the New Jersey legislature exempted the society from local taxes and authorized it to engage freely in manufacturing and selling, acquire real estate, improve rivers, dig canals, collect tolls on improvements, and incorporate the town of Paterson, named in honor of Hamilton's old friend, Governor William Paterson, who took charge of the project. Hamilton planned to but British machinery (which was not for export) and bring British craftsmen, engineers and managers to the United States, but paid too little attention to the weak qualifications of his "experts.". He did raise some $600,000, including $25,000 from banks in Amsterdam.

The Society purchased 700 acres from Dutch farmers for $8,320 at the Great Falls of the Passaic River, and built a small cotton factory. In 1794 dissatisfaction among the workers led to the closing of the mill, the first lockout in American history. Jefferson and Madison made political attacks denouncing factories as dangerous to the yeoman ethic and suggesting without evidence (but correctly) that Hamilton was using Treasury influence to get funding. After 1796, when manufacturing was abandoned; the S.U.M. eventually prospered as a real estate operation leasing sites and furnishing water power and capital to other manufacturing enterprises. The S.U.M. was Hamilton's mistake--a premature enterprise run by speculators rather than expert industrialists. The textile mills in Rhode Island set up about the same time by Samuel Slater became the nucleus of the industrial revolution in America; Slater used copies of British machines from stolen designs. [9]

Family Life

In spring 1779, Hamilton asked his friend John Laurens to find him a wife in South Carolina:[10]

"She must be young, handsome (I lay most stress upon a good shape) Sensible (a little learning will do), well bred. . . chaste and tender (I am an enthusiast in my notions of fidelity and fondness); of some good nature, a great deal of generosity (she must neither love money nor scolding, for I dislike equally a termagant and an oeconomist). In politics, I am indifferent what side she may be of; I think I have arguments that will safely convert her to mine. As to religion a moderate stock will satisfy me. She must believe in god and hate a saint. But as to fortune, the larger stock of that the better."

Hamilton found his own bride, Elizabeth Schulyer, daughter of General Philip Schuyler. She met all his criteria and their marriage in 1780 allied Hamilton with one of the richest and most powerful families of New York state. They had ten children.[11]

Notes

- ↑ Ambrose and Martin, ed. The Many Faces of Alexander Hamilton (2006) p. 11

- ↑ Freeman, Alexander Hamilton: Writings pp 6-9

- ↑ Freeman, Alexander Hamilton: Writings pp 10-43.

- ↑ Chernow p. 90; the title of chief of staff had not been invented.

- ↑ Morris, ed. 39-42

- ↑ May 19, 1777 letter to Gouverneur Morris in Freeman, Alexander Hamilton: Writings pp 46-48 and Lodge, ed. 9:72

- ↑ McDonald, Alexander Hamilton, 163–88; Elkins and McKitrick, Age of Federalism, 114–23

- ↑ Edling, "'So Immense a Power in the Affairs of War': Alexander Hamilton and the Restoration of Public Credit." (2007)

- ↑ Miller 300-302; Mitchell (1976) 262-41

- ↑ Freeman, Alexander Hamilton: Writings p. 60

- ↑ Chernow, ch 7