György Ligeti: Difference between revisions

imported>Mikael Tosti (→Awards) |

Pat Palmer (talk | contribs) mNo edit summary |

||

| (6 intermediate revisions by 4 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{subpages}} | {{subpages}} | ||

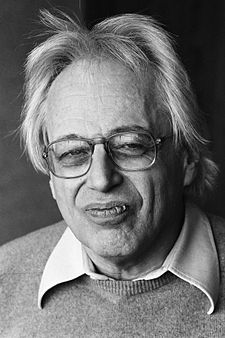

{{Image|György Ligeti (1984).jpg|right|225px|György Ligeti in 1984.}} | |||

'''György Sándor Ligeti''' ({{ | '''György Sándor Ligeti''' ({{IPA|ˈɟørɟ ˈliɡɛti}}; [[May 28]], 1923–[[June 12]], 2006) was a [[Jew]]ish [[Hungary|Hungarian]] [[composer]] born in [[Romania]] who later became an [[Austria]]n citizen. Many of his works are well known in classical music circles, but among the general public, he is probably best known for his opera ''[[Le Grand Macabre]]'' and the various pieces which feature prominently in the [[Stanley Kubrick]] films ''[[2001: A Space Odyssey (film)|2001: A Space Odyssey]]'', ''[[The Shining (film)|The Shining]]'', and ''[[Eyes Wide Shut]]''. | ||

==Biography== | ==Biography== | ||

| Line 9: | Line 9: | ||

Ligeti received his initial musical training in the conservatory in Kolozsvár. His education was interrupted in 1943 when, as a Jew, he was [[Holocaust#Hungary|forced to labor]] by the Nazis. At the same time his parents, brother, and other relatives were deported to the [[Auschwitz concentration camp]], his mother being the only survivor. | Ligeti received his initial musical training in the conservatory in Kolozsvár. His education was interrupted in 1943 when, as a Jew, he was [[Holocaust#Hungary|forced to labor]] by the Nazis. At the same time his parents, brother, and other relatives were deported to the [[Auschwitz concentration camp]], his mother being the only survivor. | ||

Following the war, Ligeti returned to his studies in [[Budapest]], graduating in 1949. He studied under [[Pál Kadosa]], [[Ferenc Farkas]], [[Zoltán Kodály]] and [[Sandor Veress|Sándor Veress]]. He went on to do [[ethnomusicology|ethnomusicological]] work on [[Romania]]n [[folk music]], but after a year returned to his old school in Budapest, this time as a teacher of [[harmony]], [[counterpoint]] and [[musical analysis]]. However, communications between Hungary and the west had been cut off by the [[communism|communist]] government, and Ligeti had to secretly listen to [[radio]] broadcasts to keep abreast of musical developments. In December of | Following the war, Ligeti returned to his studies in [[Budapest]], graduating in 1949. He studied under [[Pál Kadosa]], [[Ferenc Farkas]], [[Zoltán Kodály]] and [[Sandor Veress|Sándor Veress]]. He went on to do [[ethnomusicology|ethnomusicological]] work on [[Romania]]n [[folk music]], but after a year returned to his old school in Budapest, this time as a teacher of [[harmony]], [[counterpoint]] and [[musical analysis]]. However, communications between Hungary and the west had been cut off by the [[communism|communist]] government, and Ligeti had to secretly listen to [[radio]] broadcasts to keep abreast of musical developments. In December of 1956, two months after the [[Hungarian revolution]] was put down by the Soviet Army, he fled to [[Vienna]] and eventually took Austrian citizenship. | ||

There, he was able to meet several key [[avant-garde]] figures from whom he had been cut off in Hungary. These included the composers [[Karlheinz Stockhausen]] and [[Gottfried Michael Koenig]], both then working on groundbreaking [[electronic music]]. Ligeti worked in the same [[Cologne]] studio as them, and he was inspired by the sounds he was able to create there. However, he produced little electronic music of his own, instead concentrating on instrumental works which often contain electronic-sounding textures. | There, he was able to meet several key [[avant-garde]] figures from whom he had been cut off in Hungary. These included the composers [[Karlheinz Stockhausen]] and [[Gottfried Michael Koenig]], both then working on groundbreaking [[electronic music]]. Ligeti worked in the same [[Cologne]] studio as them, and he was inspired by the sounds he was able to create there. However, he produced little electronic music of his own, instead concentrating on instrumental works which often contain electronic-sounding textures. | ||

| Line 17: | Line 17: | ||

Ligeti took a teaching post at the [[Hamburg Hochschule für Musik und Theater]] in 1973, retiring in 1989. In the early [[1980s]], he suffered from heart troubles, leading to an absence from the musical scene for several years until he reappeared with the ''Horn Trio'' (1982). From then on, his output was plentiful through the 1980s and 1990s. However, health problems returned after the turn of the millennium, and no further pieces appeared after the song cycle ''Síppal, dobbal, nádihegedüvel'' ("With Pipes, Drums, Fiddles", 2000). | Ligeti took a teaching post at the [[Hamburg Hochschule für Musik und Theater]] in 1973, retiring in 1989. In the early [[1980s]], he suffered from heart troubles, leading to an absence from the musical scene for several years until he reappeared with the ''Horn Trio'' (1982). From then on, his output was plentiful through the 1980s and 1990s. However, health problems returned after the turn of the millennium, and no further pieces appeared after the song cycle ''Síppal, dobbal, nádihegedüvel'' ("With Pipes, Drums, Fiddles", 2000). | ||

Ligeti died in Vienna on [[June 12]], | Ligeti died in Vienna on [[June 12]], 2006. Although it was known that Ligeti had been ill for several years and had used a wheelchair the last three years of his life, his family declined to release the cause of his death. | ||

Aside from his musical interests, Ligeti expressed fondness for the [[fractal geometry]] of [[Benoît Mandelbrot]], and the writings of [[Lewis Carroll]] and [[Douglas R. Hofstadter]]. | Aside from his musical interests, Ligeti expressed fondness for the [[fractal geometry]] of [[Benoît Mandelbrot]], and the writings of [[Lewis Carroll]] and [[Douglas R. Hofstadter]]. | ||

| Line 31: | Line 31: | ||

Upon arriving in [[Cologne]], he began to write electronic music alongside [[Karlheinz Stockhausen]]. He produced only three works in this medium, however, including ''Glissandi'' (1957) and ''Artikulation'' (1958), before returning to instrumental work. His music appears to have been subsequently influenced by his electronic experiments, and many of the sounds he created resembled electronic textures. ''Apparitions'' (1958-59) was the first work which brought him to critical attention, but it is his next work, ''Atmosphères'', which is better known today. It was used, along with excerpts from ''Lux Aeterna'' and ''Requiem'', in the soundtrack to [[Stanley Kubrick|Kubrick's]] ''[[2001: A Space Odyssey (film)|2001: A Space Odyssey]]'' but without Ligeti's permission. | Upon arriving in [[Cologne]], he began to write electronic music alongside [[Karlheinz Stockhausen]]. He produced only three works in this medium, however, including ''Glissandi'' (1957) and ''Artikulation'' (1958), before returning to instrumental work. His music appears to have been subsequently influenced by his electronic experiments, and many of the sounds he created resembled electronic textures. ''Apparitions'' (1958-59) was the first work which brought him to critical attention, but it is his next work, ''Atmosphères'', which is better known today. It was used, along with excerpts from ''Lux Aeterna'' and ''Requiem'', in the soundtrack to [[Stanley Kubrick|Kubrick's]] ''[[2001: A Space Odyssey (film)|2001: A Space Odyssey]]'' but without Ligeti's permission. | ||

''Atmosphères'' (1961) is written for large [[orchestra]]. It is seen as a key piece in Ligeti's output, laying out many of the concerns he would explore through the | ''Atmosphères'' (1961) is written for large [[orchestra]]. It is seen as a key piece in Ligeti's output, laying out many of the concerns he would explore through the 1960s. Out of the four elements of music, [[melody]], [[harmony]], [[rhythm]] and [[timbre]], the piece almost completely abandons the first three, concentrating on the texture of the sound, a technique known as [[sound mass]]. It opens with what must be one of the largest [[cluster chord]]s ever written - every note in the [[chromatic scale]] over a range of five octaves is played at once. Out of the fifty-five string players ushering in the first chord, not one plays the same note. The piece seems to grow out of this initial massive, but very quiet, [[chord (music)|chord]], with the textures always changing. | ||

Ligeti coined the term "[[micropolyphony]]" for the compositional technique used in ''Atmosphères'', ''Apparitions'' and his other works of the time. He explained micropolyphony as follows: "The complex polyphony of the individual parts is embodied in a harmonic-musical flow, in which the harmonies do not change suddenly, but merge into one another; one clearly discernible interval combination is gradually blurred, and from this cloudiness it is possible to discern a new interval combination taking shape." | Ligeti coined the term "[[micropolyphony]]" for the compositional technique used in ''Atmosphères'', ''Apparitions'' and his other works of the time. He explained micropolyphony as follows: "The complex polyphony of the individual parts is embodied in a harmonic-musical flow, in which the harmonies do not change suddenly, but merge into one another; one clearly discernible interval combination is gradually blurred, and from this cloudiness it is possible to discern a new interval combination taking shape." | ||

From the [[1970s]], Ligeti turned away from total chromaticism and began to concentrate on rhythm. Pieces such as ''[[Continuum (Ligeti)|Continuum]]'' (1970) and ''Clocks and Clouds'' (1972-3) were written before he heard the music of [[Steve Reich]] and [[Terry Riley]] in 1972, yet the second of his ''Three Pieces for Two Pianos'', "Self-portrait with Reich and Riley (and Chopin in the background)," commemorates this affirmation and influence. He also became interested in the rhythmic aspects of [[African music]], specifically that of the [[Pygmies]]. In the mid-'70s he wrote his first opera, ''[[Le Grand Macabre]]'', a work of absurd theatre with many | From the [[1970s]], Ligeti turned away from total chromaticism and began to concentrate on rhythm. Pieces such as ''[[Continuum (Ligeti)|Continuum]]'' (1970) and ''Clocks and Clouds'' (1972-3) were written before he heard the music of [[Steve Reich]] and [[Terry Riley]] in 1972, yet the second of his ''Three Pieces for Two Pianos'', "Self-portrait with Reich and Riley (and Chopin in the background)," commemorates this affirmation and influence. He also became interested in the rhythmic aspects of [[African music]], specifically that of the [[Pygmies]]. In the mid-'70s he wrote his first opera, ''[[Le Grand Macabre]]'', a work of absurd theatre with many eschatological references. | ||

His music of the 1980s and '90s continued to emphasize complex mechanical rhythms, often in a less densely chromatic idiom (tending to favor displaced [[major]] and [[minor triad]]s and [[musical mode|polymodal]] structures). Particularly significant are the ''[[Études pour piano]]'' (Book I, 1985; Book II, 1988-94; Book III 1995-2001), which draw from such diverse sources as [[gamelan]], African [[polyrhythm]]s, Bartók, [[Conlon Nancarrow]], and [[Bill Evans]]. Other notable works in this vein include the ''Horn Trio'' (1982), the ''Piano Concerto'' (1985-88), the ''Violin Concerto'' (1992), and the a cappella ''Nonsense Madrigals'' (1993), one of which sets the text of the [[alphabet]]. | His music of the 1980s and '90s continued to emphasize complex mechanical rhythms, often in a less densely chromatic idiom (tending to favor displaced [[major]] and [[minor triad]]s and [[musical mode|polymodal]] structures). Particularly significant are the ''[[Études pour piano]]'' (Book I, 1985; Book II, 1988-94; Book III 1995-2001), which draw from such diverse sources as [[gamelan]], African [[polyrhythm]]s, Bartók, [[Conlon Nancarrow]], and [[Bill Evans]]. Other notable works in this vein include the ''Horn Trio'' (1982), the ''Piano Concerto'' (1985-88), the ''Violin Concerto'' (1992), and the a cappella ''Nonsense Madrigals'' (1993), one of which sets the text of the [[alphabet]]. | ||

| Line 126: | Line 126: | ||

*[[Polar Music Prize]] (2004) | *[[Polar Music Prize]] (2004) | ||

== | ==Attribution== | ||

{{WPAttribution}} | |||

== | ==Footnotes== | ||

<small> | |||

<references> | |||

</references> | |||

</small> | |||

[[Category:Suggestion Bot Tag]] | |||

Latest revision as of 09:42, 25 August 2024

György Sándor Ligeti (ˈɟørɟ ˈliɡɛti; May 28, 1923–June 12, 2006) was a Jewish Hungarian composer born in Romania who later became an Austrian citizen. Many of his works are well known in classical music circles, but among the general public, he is probably best known for his opera Le Grand Macabre and the various pieces which feature prominently in the Stanley Kubrick films 2001: A Space Odyssey, The Shining, and Eyes Wide Shut.

Biography

Ligeti was born in Dicsőszentmárton (Romanian Diciosânmartin, now Târnăveni), in the Transylvania region of Romania. Dicsőszentmárton was then a mainly Hungarian town with a large Jewish population. He moved to Kolozsvár ((Romanian Cluj) with his family when he was 6 and he was not to return to the town of his birth until the 1990s.

Ligeti received his initial musical training in the conservatory in Kolozsvár. His education was interrupted in 1943 when, as a Jew, he was forced to labor by the Nazis. At the same time his parents, brother, and other relatives were deported to the Auschwitz concentration camp, his mother being the only survivor.

Following the war, Ligeti returned to his studies in Budapest, graduating in 1949. He studied under Pál Kadosa, Ferenc Farkas, Zoltán Kodály and Sándor Veress. He went on to do ethnomusicological work on Romanian folk music, but after a year returned to his old school in Budapest, this time as a teacher of harmony, counterpoint and musical analysis. However, communications between Hungary and the west had been cut off by the communist government, and Ligeti had to secretly listen to radio broadcasts to keep abreast of musical developments. In December of 1956, two months after the Hungarian revolution was put down by the Soviet Army, he fled to Vienna and eventually took Austrian citizenship.

There, he was able to meet several key avant-garde figures from whom he had been cut off in Hungary. These included the composers Karlheinz Stockhausen and Gottfried Michael Koenig, both then working on groundbreaking electronic music. Ligeti worked in the same Cologne studio as them, and he was inspired by the sounds he was able to create there. However, he produced little electronic music of his own, instead concentrating on instrumental works which often contain electronic-sounding textures.

From this time, Ligeti's work became better known and respected, and his best known work might be said to span the period from Apparitions (1958-9) to Lontano (1967), although his later opera, Le Grand Macabre (1978) is also fairly well-known. In more recent years, his three books of piano Études have become quite popular thanks to recordings made by Pierre-Laurent Aimard, Fredrik Ullén, and others.

Ligeti took a teaching post at the Hamburg Hochschule für Musik und Theater in 1973, retiring in 1989. In the early 1980s, he suffered from heart troubles, leading to an absence from the musical scene for several years until he reappeared with the Horn Trio (1982). From then on, his output was plentiful through the 1980s and 1990s. However, health problems returned after the turn of the millennium, and no further pieces appeared after the song cycle Síppal, dobbal, nádihegedüvel ("With Pipes, Drums, Fiddles", 2000).

Ligeti died in Vienna on June 12, 2006. Although it was known that Ligeti had been ill for several years and had used a wheelchair the last three years of his life, his family declined to release the cause of his death.

Aside from his musical interests, Ligeti expressed fondness for the fractal geometry of Benoît Mandelbrot, and the writings of Lewis Carroll and Douglas R. Hofstadter.

Ligeti was the grand-nephew of the great violinist Leopold Auer. Ligeti's son, Lukas Ligeti, is a composer and percussionist based in New York City.

Music

Ligeti's earliest works are an extension of the musical language of his countryman Béla Bartók. The piano pieces, Musica Ricercata (1951-53), for example, are often compared to Bartók's set of piano works, Mikrokosmos. Ligeti's set comprises eleven pieces in all. The first uses almost exclusively just one pitch class, A, heard in multiple octaves. Only at the very end of the piece is a second note, D, heard. The second piece then adds a third note to these two, the third piece adds a fourth note, and so on, so that in the eleventh piece all twelve notes of the chromatic scale are present.

Already at this early stage in his career, Ligeti was affected by the communist regime in Hungary at that time. The tenth piece of Musica Ricercata was banned by the authorities on account of it being "decadent." It seems that it was thus branded owing to its liberal use of minor second intervals. Given the far more radical direction that Ligeti was looking to take his music in, it is hardly surprising that he felt the need to leave Hungary.

Upon arriving in Cologne, he began to write electronic music alongside Karlheinz Stockhausen. He produced only three works in this medium, however, including Glissandi (1957) and Artikulation (1958), before returning to instrumental work. His music appears to have been subsequently influenced by his electronic experiments, and many of the sounds he created resembled electronic textures. Apparitions (1958-59) was the first work which brought him to critical attention, but it is his next work, Atmosphères, which is better known today. It was used, along with excerpts from Lux Aeterna and Requiem, in the soundtrack to Kubrick's 2001: A Space Odyssey but without Ligeti's permission.

Atmosphères (1961) is written for large orchestra. It is seen as a key piece in Ligeti's output, laying out many of the concerns he would explore through the 1960s. Out of the four elements of music, melody, harmony, rhythm and timbre, the piece almost completely abandons the first three, concentrating on the texture of the sound, a technique known as sound mass. It opens with what must be one of the largest cluster chords ever written - every note in the chromatic scale over a range of five octaves is played at once. Out of the fifty-five string players ushering in the first chord, not one plays the same note. The piece seems to grow out of this initial massive, but very quiet, chord, with the textures always changing.

Ligeti coined the term "micropolyphony" for the compositional technique used in Atmosphères, Apparitions and his other works of the time. He explained micropolyphony as follows: "The complex polyphony of the individual parts is embodied in a harmonic-musical flow, in which the harmonies do not change suddenly, but merge into one another; one clearly discernible interval combination is gradually blurred, and from this cloudiness it is possible to discern a new interval combination taking shape."

From the 1970s, Ligeti turned away from total chromaticism and began to concentrate on rhythm. Pieces such as Continuum (1970) and Clocks and Clouds (1972-3) were written before he heard the music of Steve Reich and Terry Riley in 1972, yet the second of his Three Pieces for Two Pianos, "Self-portrait with Reich and Riley (and Chopin in the background)," commemorates this affirmation and influence. He also became interested in the rhythmic aspects of African music, specifically that of the Pygmies. In the mid-'70s he wrote his first opera, Le Grand Macabre, a work of absurd theatre with many eschatological references.

His music of the 1980s and '90s continued to emphasize complex mechanical rhythms, often in a less densely chromatic idiom (tending to favor displaced major and minor triads and polymodal structures). Particularly significant are the Études pour piano (Book I, 1985; Book II, 1988-94; Book III 1995-2001), which draw from such diverse sources as gamelan, African polyrhythms, Bartók, Conlon Nancarrow, and Bill Evans. Other notable works in this vein include the Horn Trio (1982), the Piano Concerto (1985-88), the Violin Concerto (1992), and the a cappella Nonsense Madrigals (1993), one of which sets the text of the alphabet.

Ligeti's last works were the Hamburg Concerto for horn and chamber orchestra (1998-99, revised 2003) and the song cycle Síppal, dobbal, nádihegedüvel ("With Pipes, Drums, Fiddles", 2000).

Works

Opera

- Aventures (1962)

- Nouvelles Aventures (1962-65)

- Le Grand Macabre (1975-77, second version 1996)

Orchestral

- Concert românesc (1951)

- Apparitions (1958-59)

- Atmosphères (1961)

- Lontano (1967)

- Ramifications, for string orchestra or 12 solo strings (1968-69)

- Chamber Concerto, for 13 instrumentalists (1969-70)

- Melodien (1971)

- San Francisco Polyphony (1973-74)

Concertante

- Cello Concerto (1966)

- Double Concerto for Flute, Oboe and Orchestra (1972)

- Piano Concerto (1985-88)

- Violin Concerto (1992)

- Hamburg Concerto, for Horn and Chamber Orchestra with 4 Obligato Natural Horns (1998-99, revised 2003)

Vocal/Choral

- Requiem, for Soprano and Mezzo Soprano solo, mixed Chorus and Orchestra (1963-65)

- Lux Aeterna, for 16 solo voices (1966)

- Clocks and Clouds, for 12 female voices (1973)

- Nonsense madrigals, for 6 male voices (1988-1993)

- Síppal, dobbal, nádihegedüvel (With Pipes, Drums, Fiddles) (2000)

Chamber/Instrumental

- Sonate, for solo cello (1948/1953)

- Andante and Allegro, for string quartet (1950)

- Baladǎ şi joc (Ballad and Dance), for two violins (1950)

- Six Bagatelles for Wind Quintet (1953)

- String Quartet No. 1 Métamorphoses nocturnes (1953-54)

- String Quartet No. 2 (1968)

- Ten Pieces for Wind Quintet (1968)

- Trio for Violin, Horn and Piano (1982)

- Hommage à Hilding Rosenberg, for violin and cello (1982)

- Sonata for Solo Viola (1991-94)

Keyboard

Piano

- Induló (March), four-hands (1942)

- Polifón etüd (Polyphonic Étude), four-hands (1943)

- Capriccio nº 1 & nº 2 (1947)

- Invention (1948)

- Három lakodalmi tánc (Three Wedding Dances), four-hands (1950)

- Sonatina, four-hands (1950)

- Musica ricercata (1951-1953)

- Trois Bagatelles (1961)

- Three Pieces for Two Pianos (1976)

- Études pour piano, Book 1, six etudes (1985)

- Études pour piano, Book 2, eight etudes (1988-94)

- Études pour piano, Book 3, four etudes (1995-2001)

Organ

- Ricercare - Ommagio a Girolamo Frescobaldi (1951)

- Volumina (1961-62, revised 1966)

- Two Studies for Organ (1967, 1969)

Harpsichord

- Continuum (1968)

- Passacaglia ungherese (1978)

- Hungarian Rock (Chaconne) (1978)

Electronic

- Glissandi, electronic music (1957)

- Artikulation, electronic music (1958)

Miscellaneous

Awards

- Grawemeyer Award for Music Composition (Etudes for Piano) (1986)

- Sonning Music Price, Denmark (1990)

- Schock Prize for Musical Arts (1995)

- Wolf Prize, Israel (1996)

- Kyoto Award (2001)

- Kossuth Price, Hungary (2003)

- Polar Music Prize (2004)

Attribution

- Some content on this page may previously have appeared on Wikipedia.

Footnotes