Denver, Colorado: Difference between revisions

imported>Richard Jensen mNo edit summary |

(A few edits, including significant changes to the introduction) |

||

| (29 intermediate revisions by 8 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{subpages}} | |||

'''Denver''' is | {{TOC|right}} | ||

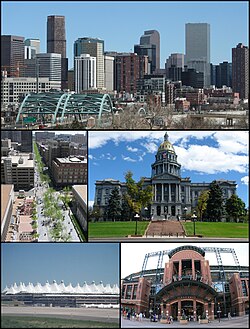

{{Image|Montage Denver.jpg|left|250px|Denver, Colorado skyline, 16th St mall, capitol, airport, and Coors Field in 2009}} | |||

'''Denver, Colorado''' is a rapidly growing city of 715,522 people<ref name=2020census>715,522 was the official population as of the 2020 census.</ref> and the capital of [[Colorado (U.S. state)|Colorado]]. The metropolitan area has more than 3 million people. The city is located close to the Rocky Mountains at an elevation of about 5,280′, and is thus sometimes called the ''Mile High City''. Denver is a federal regional government center and has the highest concentration of U.S. offices outside [[Washington, D.C.]]. The metropolitan area is a hub of financial services, aviation, outdoor recreation, energy, and technology. | |||

==Geography== | ==Geography== | ||

The city itself covers 107 square miles (277 sq km), 5,280 feet (1,610 meters) | The city itself covers 107 square miles (277 sq km), 5,280 feet (1,610 meters); on average about one mile above sea level, it is called the Mile High City. Winding through Denver are the South Platte River and Cherry Creek. The Rockies provide a spectacular backdrop for the city, with [[Mount Blue Sky]] clearly visible on many days, a peak over 14,000 feet high. | ||

Denver is a spacious city of parks, tree-lined streets, broad avenues, old buildings, and modern skyscrapers. Its climate is mild and dry, primarily because the Rockies divert moisture-bearing winds away from the area. Formerly known for its clear sky, it was long a destination for people suffering from tuberculosis. Since 1950, however, exhaust fumes from automobiles and trucks has caused serious air pollution. The average temperature in July, the warmest month, is 73°F (23°C | Denver is a spacious city of parks, tree-lined streets, broad avenues, old buildings, and modern skyscrapers. Its climate is mild and dry, primarily because the Rockies divert moisture-bearing winds away from the area. Formerly known for its clear sky, it was long a destination for people suffering from tuberculosis. Since 1950, however, exhaust fumes from automobiles and trucks has caused serious air pollution, but since the 1970s an emission testing and registration program coupled with modern vehicles has greatly reduced per capita vehicle air pollution. The average temperature in July, the warmest month, is 73°F (23°C), and the average temperature in January, the coldest month, is 28.5°F. (-2°C). Annual precipitation is only 15 inches (380 mm), and the city has an average of 250 clear or partly cloudy days a year. The sunshine makes it a very popular tourist destination. | ||

==Demography== | |||

The city's population was 715,522 in 2020. The Denver–Aurora–Boulder Combined Statistical Area had an estimated 2013 population of 3,277,309 and ranked as the 18th most populous U.S. metropolitan area. Denver is the most populous city within a radius centered in the city and of 550-mile (890 km) magnitude. | |||

Minority communities in Denver include a rapidly growing [[Latino history|Latino]] population chiefly of Mexican ancestry. | |||

Suburban '''Aurora''', founded in 1891, exploded in population after 1990, reaching 386,000 in 2020. Nearby '''Boulder''' is known both for research, high technology, and liberal politics. | |||

The first Chinese settlers arrived in 1869; two Chinatowns emerged, one a commercial area, the other a residential ghetto. The Chinese population peaked at 1000 in, then declined to 100 in 1940. In the 1950s urban renewal projects demolished the Chinatowns. A new wave of 15,000 highly educated Chinese arrived after 1965, but they were widely dispersed in the metro area.<ref>William Wei, "History and Memory: the Story of Denver's Chinatown." ''Colorado Heritage'' 2002 (Aut): 2-13. Issn: 0272-9377 </ref> | |||

==Economy== | ==Economy== | ||

| Line 23: | Line 25: | ||

==Transportation== | ==Transportation== | ||

Denver was at a disadvantage in the 19th century because the transcontinental routes ran 200 miles north of the city, through Cheyenne, Wyoming, which became the primary way station for wagon trains, stage lines, and rail lines passing through the northern Rockies. Pilots at first preferred Cheyenne, and it won the first round of competition when the US Post Office decided to fly mail through Wyoming in 1920. Denver business leaders never stopped competing, however, and struggled to get a share of the traffic. By the mid-1930s they convinced some passenger airlines to move their operations to Colorado. After World War II, Denver wrested full control of Rocky Mountain air traffic from Cheyenne, making the city's Stapleton airport the major regional hub.<ref> Roger D. Launius, and Jessie L. Embry, "Cheyenne Versus Denver: City Rivalry and the Quest for Transcontinental Air Routes." ''Annals of Wyoming'' 1996 68(3): 8-23. Issn: 1086-7368 </ref> | |||

Denver International Airport (DIA) is one of the world's ten busiest facilities and is the hub for United and Frontier airlines. DIA has four north-south runways and two east-west runways. The concourses and Jeppesen Terminal (with its Teflon-coated fiberglass roof) are in the center of the airfield. 95 airlines operated 1175 passenger flights daily in 2006, with 130,000 passengers a day. The airport is operating close to capacity and plans to spend $1 billion through 2013 on its concourses, concession areas, security checkpoints, parking lots and baggage system.<ref> See Chris Walsh, "DIA bursting at the seams," ''Rocky Mountain News'' September 29, 2007 at [http://www.rockymountainnews.com/drmn/airlines/article/0,2777,DRMN_23912_5710157,00.html]</ref> There are numerous flights to Mexico and Canada, and three to Europe. 44% of the passengers are making connections in Denver; Los Angeles is the chief point of origin. DIA replaced inner-city Stapleton International Airport (1929-1995). Once open range country, the area near DIA is undergoing rapid construction of homes, hotels and warehouses. | Denver International Airport (DIA) is one of the world's ten busiest facilities and is the hub for United and Frontier airlines. DIA has four north-south runways and two east-west runways. The concourses and Jeppesen Terminal (with its Teflon-coated fiberglass roof) are in the center of the airfield. 95 airlines operated 1175 passenger flights daily in 2006, with 130,000 passengers a day. The airport is operating close to capacity and plans to spend $1 billion through 2013 on its concourses, concession areas, security checkpoints, parking lots and baggage system.<ref> See Chris Walsh, "DIA bursting at the seams," ''Rocky Mountain News'' September 29, 2007 at [http://www.rockymountainnews.com/drmn/airlines/article/0,2777,DRMN_23912_5710157,00.html]</ref> There are numerous flights to Mexico and Canada, and three to Europe. 44% of the passengers are making connections in Denver; Los Angeles is the chief point of origin. DIA replaced inner-city Stapleton International Airport (1929-1995). Once open range country, the area near DIA is undergoing rapid construction of homes, hotels and warehouses. | ||

The Valley Highway, now Interstate I-25, had been planned since 1938; it was delayed by the war but construction began in 1948. By the time of its opening in 1958, the 11-mile north-south "superhighway" required 57 bridges, 17 interchanges, and a relocation of two-thirds of a mile of the South Platte River. The Valley Highway, by running through metropolitan Denver, made the city more accessible, led to a commercial boom for Denver and opened up the suburbs to development. | |||

In 2006 the $1.67 billion T-REX project widened Interstates 25 and I-225 and added 19 miles of light rail connecting Metro Denver's two largest employment centers: The Central Business District and the Denver Tech Center. | |||

==Downtown== | ==Downtown== | ||

At the center of downtown is the Denver Civic Center, a 40 acre (16-hectare) complex of parks and government buildings. At opposite ends of the Center are the City-County Building and the State Capitol. The Capitol is 272 feet (83 meters) high and has a dome covered with local gold. By the time the capitol was completed in 1900 (at 170% over budget) the building—a difficult-to-maintain hodgepodge of dirt-collecting nooks and crannies, grumblers said—was instantly too small. In the 21st century the debate is whether Colorado's aging yet "most important building" deserves a mere nip and tuck or an extreme makeover.<ref> Derek R. Everett, ''The Colorado State Capitol: History, Politics, Preservation.'' 2005.</ref> Nearby are the Art Museum, and the Denver Public Library (which contains more than one million volumes, especially famous for its research collection in western history). The United States Mint makes half the nation's coins. Until the 1950s buildings in Denver could not be higher than 12 stories, but since then a number of skyscrapers more than 40 stories tall have been added to the city skyline, including the Arco Tower, Anaconda Tower, Great West Plaza, and the Amoco Building. During the 1970s an extensive urban renewal program was undertaken in downtown Denver, leading to the creation of a three-square block convention center and an elaborate theater complex, the Denver Center for the Performing Arts. | At the center of downtown is the Denver Civic Center, a 40 acre (16-hectare) complex of parks and government buildings. At opposite ends of the Center are the City-County Building and the State Capitol. The Capitol is 272 feet (83 meters) high and has a dome covered with local gold. By the time the capitol was completed in 1900 (at 170% over budget) the building—a difficult-to-maintain hodgepodge of dirt-collecting nooks and crannies, grumblers said—was instantly too small. In the 21st century the debate is whether Colorado's aging yet "most important building" deserves a mere nip and tuck or an extreme makeover.<ref> Derek R. Everett, ''The Colorado State Capitol: History, Politics, Preservation.'' 2005.</ref> Nearby are the Art Museum, and the Denver Public Library (which contains more than one million volumes, especially famous for its research collection in western history). The United States Mint makes half the nation's coins. Until the 1950s buildings in Denver could not be higher than 12 stories, but since then a number of skyscrapers more than 40 stories tall have been added to the city skyline, including the Arco Tower, Anaconda Tower, Great West Plaza, and the Amoco Building. During the 1970s an extensive urban renewal program was undertaken in downtown Denver, leading to the creation of a three-square block convention center and an elaborate theater complex, the Denver Center for the Performing Arts. | ||

==Medical== | ==Medical== | ||

Across the western landscape of the United States, health was a natural resource, mined and sold by late-19th- and 20th-century town boosters and physicians to those afflicted with such chronic pulmonary illnesses as tuberculosis and asthma. Denver was especially important as a destination and the city became the largest medical center for the mountain states by 1900.<ref> Gregg Mitman, "Geographies of Hope: Mining the Frontiers of Health in Denver and Beyond, 1870-1965." ''Osiris'' 2004 19: 93-111. Issn: 0369-7827 </ref> St. Luke's Hospital was established by the Episcopal Church in 1881; Presbyterian Hospital opened in 1926. Both operated nursing schools . In 1992 St. Luke's merged with Presbyterian Hospital, which subsequently merged with others to form the HealthONE hospital system.<ref> Rebecca Hunt, "Healers on the Hill: St. Luke's and Presbyterian Hospitals of Denver." ''Colorado Heritage'' 2005 (Sum): 2-17. Issn: 0272-9377 </ref> The Denver Homeopathic Hospital opened in 1894 to offer alternatives to the medical practices of "allopathic" medicine, the mainstream treatments of the day. Friction arose among the homeopathic physicians, and the hospital closed in 1909.<ref> Steve Grinstead, "Alternative Healing At The Crossroads: Denver's Homeopathic Hospital Succumbs To Modern Medicine." ''Colorado Heritage'' 2005 (Sum): 18-29. Issn: 0272-9377 </ref> The Swedish National Sanatorium was established in 1905 by the Swedish community, as a national tuberculosis sanatorium. It was reorganized in 1956 and later became the Swedish Medical Center. <ref> Rebecca Hunt, "Swedish National Sanatorium: Building Community in a Swedish-American Tuberculosis Sanatorium, 1905-59." ''Colorado Heritage'' 2005 (Sum): 30-46. ISSN: 0272-9377 </ref> After World War II the Jewish National Home for Asthmatic Children became the Children's Asthma Research Institute and Hospital. To the dismay of the city of Denver, the University of Colorado Medical School and associated hospitals left the city in 2007, taking 30,000 high-paying jobs, for a huge new campus in Aurora centered on the former Fitzsimons Army Medical Center. It solidified the Denver Metro Area the premier medical center in a thousand mile radius. | Across the western landscape of the United States, health was a natural resource, mined and sold by late-19th- and 20th-century town boosters and physicians to those afflicted with such chronic pulmonary illnesses as tuberculosis and asthma. Denver was especially important as a destination and the city became the largest medical center for the mountain states by 1900.<ref> Gregg Mitman, "Geographies of Hope: Mining the Frontiers of Health in Denver and Beyond, 1870-1965." ''Osiris'' 2004 19: 93-111. Issn: 0369-7827 </ref> Religious and ethnic groups established the most important hospitals. St. Luke's Hospital was established by the Episcopal Church in 1881; Presbyterian Hospital opened in 1926. Both operated nursing schools . In 1992 St. Luke's merged with Presbyterian Hospital, which subsequently merged with others to form the HealthONE hospital system.<ref> Rebecca Hunt, "Healers on the Hill: St. Luke's and Presbyterian Hospitals of Denver." ''Colorado Heritage'' 2005 (Sum): 2-17. Issn: 0272-9377 </ref> The Denver Homeopathic Hospital opened in 1894 to offer alternatives to the medical practices of "allopathic" medicine, the mainstream treatments of the day. Friction arose among the homeopathic physicians, and the hospital closed in 1909.<ref> Steve Grinstead, "Alternative Healing At The Crossroads: Denver's Homeopathic Hospital Succumbs To Modern Medicine." ''Colorado Heritage'' 2005 (Sum): 18-29. Issn: 0272-9377 </ref> During 1906-15, wealthy women established The Children's Hospital of Denver, focusing its work on middle-class health concerns. The Swedish National Sanatorium was established in 1905 by the Swedish community, as a national tuberculosis sanatorium. It was reorganized in 1956 and later became the Swedish Medical Center. <ref> Rebecca Hunt, "Swedish National Sanatorium: Building Community in a Swedish-American Tuberculosis Sanatorium, 1905-59." ''Colorado Heritage'' 2005 (Sum): 30-46. ISSN: 0272-9377 </ref> Seraphine Pisko was first woman to head a major Jewish hospital when she was appointed in 1911 as secretary of Denver's National Jewish Hospital for Consumptives, Pisko skillfully and efficiently managed the institution, while advancing a personalized and nurturing philosophy of charity in contrast to efforts to centralize fund-raising and administration. | ||

After World War II the Jewish National Home for Asthmatic Children became the Children's Asthma Research Institute and Hospital. To the dismay of the city of Denver, the University of Colorado Medical School and associated hospitals left the city in 2007, taking 30,000 high-paying jobs, for a huge new campus in Aurora centered on the former Fitzsimons Army Medical Center. It solidified the Denver Metro Area as the premier medical center in a thousand mile radius, but brought into debate the state's sharply reduced budget for medical education and higher education generally. | |||

==History== | ==History== | ||

Denver was started during the turbulent Pikes Peak gold rush of 1859-1860, when thousands walked across the plains in search of wealth. Two small settlements, Denver City and Auraria, were consolidated in 1860; the city was named after the governor of Kansas. Population reached 4700 in 1860 and remained the same a decade later. The first city hall was built on stilts in the middle of a stream. Boom and bust characterized the early years, 1859-1870. In 1863 a fire destroyed much of Denver, and the next year a flash flood destroyed the precariously built city hall on stilts. | Denver was started during the turbulent Pikes Peak gold rush of 1859-1860, when thousands walked across the plains in search of wealth. Two small settlements, Denver City and Auraria, were consolidated in 1860; the city was named after the governor of Kansas. Population reached 4700 in 1860 and remained the same a decade later. The first city hall was built on stilts in the middle of a stream. Boom and bust characterized the early years, 1859-1870. In 1863 a fire destroyed much of Denver, and the next year a flash flood destroyed the precariously built city hall on stilts. | ||

In 1861 Colorado became a territory, with a governor appointed by President [[Abraham Lincoln]]. In 1867 Denver became the capital. The major obstacles to the city's growth were its isolation from the East and the Midwest and the lack of a stable income-producing economy. The Indian wars on the plains and heavy winter snowstorms east of the city were a constant threat to the connections with Kansas and points eastward. In 1863 the telegraph arrived. The coming of the railroads integrated the city further with the rest of the nation. In 1870 the Denver Pacific Railroad north to Cheyenne, Wyoming, linked into the transcontinental Union Pacific Railroad, while the Kansas Pacific Railroad linked across the plains to Kansas City. The Denver and Rio Grande Railroad south to Pueblo opened in 1871, thus making Denver the hub of all mining and ranching areas in Colorado; the population hit 36,000 in 1880. | In 1861 Colorado became a territory, with a governor appointed by President [[Abraham Lincoln]]. In 1867 Denver became the capital. The major obstacles to the city's growth were its isolation from the East and the Midwest and the lack of a stable income-producing economy. The Indian wars on the plains and heavy winter snowstorms east of the city were a constant threat to the connections with Kansas and points eastward. In 1863 the telegraph arrived. The coming of the railroads integrated the city further with the rest of the nation. In 1870 the Denver Pacific Railroad north to Cheyenne, Wyoming, linked into the transcontinental Union Pacific Railroad, while the Kansas Pacific Railroad linked across the plains to Kansas City. The Denver and Rio Grande Railroad south to Pueblo opened in 1871, thus making Denver the hub of all mining and ranching areas in Colorado; the population hit 36,000 in 1880, augmented by a steady influx of German, Irish and English workers and craftsmen. | ||

The city provided lavishly for the lusts of the rich miners visiting the city. There was a range of bawdy houses to fit every pocketbook, from the sumptuous quarters of renowned madams such as Mattie Silks and Jenny Rogers to the most squalid "cribs" located a few blocks farther north along Market Street. Gambling flourished as sharp-eyed bunco artists exploited every chance to separate miners from their hard-earned gold. Edward Chase ran scrupulously honest games in several elegant establishments and regularly entertained many of Denver's most influential leaders. By 1880 Denver's vice district ranked only slightly behind San Francisco's Barbary Coast and New Orleans's Storyville. Most of the city's seamiest attractions were within a few steps of Union Station, but newsstands sold guidebooks that provided additional addresses. Sin was good for business; visitors spent lavishly, then left town. As long as madams conducted their business discreetly, and "crib girls" did not advertise their availability too crudely, authorities took their bribes and looked the other way. Occasional cleanups and cracked downs satisfied the demands for reform.<ref> Clark Secrest. ''Hell's Belles: Prostitution, Vice, and Crime in Early Denver, with a Biography of Sam Howe, Frontier Lawman.'' 2nd ed 2002, heavily illustrated.</ref> | |||

In legitimate entertainment, music stood high, beginning with the Apollo Hall in 1859. The Denver Theatre, home of the city's first opera performance in 1864, the Tabor Grand Opera House (1881)and the Broadway Theatre (1890-1955) brought in internationally renown performers. Many other theaters were built, most of which did not last very long. Denver churches were also important venues for music performances in the last half of the 19th century.<ref> Henry Miles, "Where Music Dwells: Denver's Earliest Concert Spaces." ''Colorado Heritage'' 2002 (Sum): 32-46.</ref> There were orchestras playing classical music as early as 1892, as well as two rival orchestras in the first decade of the 20th century. The Denver Symphony Orchestra was the first professional group, debuting in November 1934 under Horace E. Tureman. Its reputation grew, especially under the conductorship of Saul Caston, who led the orchestra from 1945 through perhaps its finest years until 1963.<ref>James Michael Bailey, "Notes of Turmoil: Sixty Years of Denver's Symphony Orchestras." ''Colorado Heritage'' 1992 (Aut): 33-47. </ref> | |||

In the 1880s silver was discovered in the nearby mountains, leading Denver to a new surge of gaudiness and opulence, typified by Tabor's fancy opera house. The silver madness was as economically unstable as the gold rush 20 years before. The 10-story Brown Palace Hotel in 1893, designed by noted local architect Frank Edbrooke. In 1893 financial panic swept the nation, and the silver boom collapsed. By this time, however, the city's economy had a more stable base rooted in the agriculture of the surrounding area. | |||

Between 1870 and 1890 the city's population increased from less than 5,000 to over 100,000. In the 1880s entrepreneurs who had recently installed water supplies, sewers, trolley lines, and railroad connections moved to obtain urban gas and electric franchises. Since Denver was growing rapidly and unpredictably, franchise holders soon found themselves at the mercy of demand for costly extension of services to the outlying areas at rates no higher than those for the central city. Henry Doherty met the challenge by offering customers a three-level rate structure whose effect was to keep basic rates uniform throughout cities and suburbs and to give lower rates to higher volume (wealthier) customers. Doherty hired a large sales force to increase consumer demand for gas and electricity by replacing old kerosene lamps with gas light, and selling electric irons and gas water heaters door to door, promoting their virtues of cleanliness, comfort, convenience and economy.<ref> Mark H. Rose, ''Cities of Light and Heat: Domesticating Gas and Electricity in Urban America'' 1995. </ref> Denver's Myron W. Reed was the leading Christian socialist in the American West in the last two decades of the nineteenth century. He came to the city in 1884 as pastor of the affluent First Congregational Church. Christian socialism, for Reed, meant that the state should manage production and instill cooperation to provide what he called "the comfortable life" for all. He was a leader in the city's Charity Organization Society, even while questioning that organization's efforts to distinguish the "worthy" from the "unworthy" poor. Reed spoke out for the rights of labor unions and was voted out of his pulpit during the bitter 1894 strike at Cripple Creek. He ran for Congress as a Democrat in 1886 and worked for Colorado's Populist party in the 1890s. A former abolitionist Reed spoke out for African American and Native American rights while denouncing Chinese and eastern European immigrants as dependent tools of corporations who were lowering "American" standards of living.<ref> James A. Denton, ''Rocky Mountain Radical: Myron W. Reed, Christian Socialist.'' 1997. </ref> | |||

===Progressive era=== | |||

The city doubled between 1900 and 1920, reaching 256,000 population. Growth slowed somewhat, as the total in 1940 was 322,000, with few suburbs as yet. | |||

Local boosters created the National Stock Growers Conventions in 1898 and 1899. The National Western Stock Show began in 1907 as an annual event attracting cattlemen from a wide region. The [[Progressive Era]] brought an [[Efficiency Movement]], typified in 1902 when the city and Denver County were made coextensive;<ref>Since then both the city and the county have been governed by a nonpartisan mayor and nine-member council. </ref> Denver pioneered the juvenile court movement under Judge [[Ben Lindsey]] (1869-1943). While serving as a law clerk in Denver, Lindsey became concerned with the plight of children who were imprisoned for minor offenses. As a lawyer he secured a court appointment as guardian of orphans and other wards of the county. Later, as a judge he launched a crusade that pioneered reforms and established a juvenile court system that gained him national and international acclaim.<ref>D'Ann Campbell, "Judge Ben Lindsey and the Juvenile Court Movement, 1901-1904." ''Arizona and the West'' 1976 18(1): 5-20. Issn: 0004-1408; also [http://100.juvenilelaw.net/Judges/Lindsay.htm] </ref> Mayor Robert Speer was a prominent progressive who gave the city world leadership in building parks. Boasting itself the "Queen City of the Plains," Denver hosted the Democratic National Convention in 1908, then waited 100 years for its return. | |||

Famed evangelist and ardent prohibitionist [[Billy Sunday]] came to Denver in September and October 1914 to speak on behalf of the proposed state prohibition amendment. His revival lasted about two months, held in a specially built tabernacle near Capitol Hill. Sunday spoke to a total of 60,000 pietistic Protestants. In spite of this, the prohibition amendment was defeated in Denver, a Catholic wet stronghold; however it passed statewide; the "dry" vote was almost three times as great as that of a similar referendum held in 1912 as Colorado made saloons illegal.<ref> David A. Baldwin, "When Billy Sunday 'Saved' Colorado: That Old-time Religion and the 1914 Prohibition Amendment." ''Colorado Heritage'' 1990 (2): 34-44.</ref> | |||

Women suffrage came early, in 1893, led by married middle class women who organized first for prohibition and then for suffrage, with the goal of upholding [[Republicanism, U.S.|republican citizenship]] for women and purifying society. The Denver Fortnighly Club played a major role. Caroline Nichols Churchill, edited and published the ''Colorado Antelope'', subsequently the ''Queen Bee'', beginning in 1879 and boasted that she and her journal played a crucial role in the passage of the referendum in 1893 that granted the vote to women in Colorado. There was a strained relationship between the radical and eccentric Churchill and the mainstream women, as Churchill was a confrontational and outspoken proponent of the equal rights of minority ethnic groups.<ref> Jennifer A. Thompson, "From Travel Writer to Newspaper Editor: Caroline Churchill and the Development of Her Political Ideology Within the Public Sphere." ''Frontiers'' 1999 20(3): 42-63. Issn: 0160-9009 Fulltext: [http://links.jstor.org/sici?sici=0160-9009%281999%2920%3A3%3C42%3AFTWTNE%3E2.0.CO%3B2-K in Jstor] </ref> | |||

The nation saw a wave of strikes in 1919, as labor unions tried to preserve their wartime gains. The Amalgamated Association of Street and Railway Employees of America led a strike against the Denver Tramway Company in 1920. Rioting broke out before US Army troops were called in; seven people were killed by gunfire, none of them strikers or rioters, and fifty people were injured. The army troops stayed in Denver for a month. The union lost the strike, two-thirds of its workers lost their jobs, and organized labor was weakened severely in Denver. The Tramway Company offset its financial losses from the strike through a fare raise and survived the crisis.<ref>Stephen J. Leonard, "Bloody August: The Denver Tramway Strike of 1920." ''Colorado Heritage'' 1995 (Sum): 18-31. </ref> | |||

The [[KKK]] was briefly active in the mid-1920s. The membership a cross-section of the city's Protestants (except that the elite did not join). White Protestant men from all socioeconomic levels joined to save their communities and homes from so-called disruptive groups: Catholics, Jews, blacks, immigrants, and law violators.<ref> Robert A. Goldberg, "Beneath the Hood and Robe: a Socioeconomic Analysis of Ku Klux Klan Membership in Denver, Colorado, 1921-1925." ''Western Historical Quarterly'' 1980 11(2): 181-198. Issn: 0043-3810 Fulltext: [http://links.jstor.org/sici?sici=0043-3810%28198004%2911%3A2%3C181%3ABTHARA%3E2.0.CO%3B2-A in Jstor] </ref> | |||

During the 10 years Robert Speer served as mayor (1904-1912, 1916-1918), voters approved bond issues enabling the implementation of "City Beautiful" plans that brought Denver to the forefront of the movement nationally. Using political coalitions and reform rhetoric, urban plans, and architectural projects, Speer used City Beautiful ideals to build a power base. Opposition came from more "radically" Progressives. The roots of City Beautiful reform were in the park movement of the 1880s and the concomitant modifications in municipal government that gave officials the power to direct urban development. Speer brought nationally recognized designers including Charles Mulford Robinson, George Kessler, Frederick MacMonnies, and Edward Bennett to Denver as consultants and developed a series of City Beautiful projects that included a municipal auditorium, a bath house, memorial sculpture and pavilions, a civic center, and intra- and extra-urban parks and parkways.<ref> See Carol McMichael Reese, "The Politician and the City: Urban Form and City Beautiful Rhetoric in Progressive Era Denver." PhD dissertation U. of Texas, Austin 1992.</ref> When the Dutch-born architect Saco Rienk DeBoer arrived in Denver in 1908, he found a city mostly devoid of landscaping. Appointed as landscape architect for the city DeBoer's first assignment was to create Sunken Gardens Park. He also planted trees along several Denver streets, experimenting over the years with different varieties to find the trees most suitable to Denver's climate. His landscaping of the city parks also accommodated the automobile. In 1925, DeBoer was appointed to Denver's first zoning commission, and he planned the landscaping of the new municipal airport in 1929. His ideas for residential landscaping were carried out in Lakewood and the Cherry Hills area, and his ideas for commercial plazas were later used as models for the shopping centers of the 1950s. He also drew the plans for the City Park botanical gardens as well as the newer ones several years later.<ref>Joyce Summers, "One Man's Vision: Saco Rienk Deboer, Denver Landscape Architect" ''Colorado Heritage'' 1988 (2): 28-42. </ref> | |||

===World War II and after=== | |||

Up until World War II, Denver's economy was dependent mainly on the processing and shipping of minerals and ranch products, especially beef and lamb. During the war and in the years following, specialized industries were introduced into the city, making it a major manufacturing center. Lowry Air Force Base, Fitzsimons Army Hospital, and Fort Logan were major installations, as defense dollars spurred the local economy. Rocky Mountain Arsenal made munitions. Denverites participated in civil defense preparedness, rationing, and price controls, and sent 45,000 locals to the armed services.<ref> Stephen J. Leonard, "Denver at War: the Home Front in World War II" ''Colorado Heritage'' 1987 (4): 30-39.</ref> See also [[World War II, Homefront, U.S.]] | |||

The wartime housing shortage led to a postwar construction boom, as Denver was a magnet for many of the servicemen who had been stationed nearby in the war. The population surged in the city and spilled into farmlands that became instant suburbs. A change in the political and financial climate also brought a more progressive leadership to Denver, as the old families were pushed aside by newly arrived entrepreneurs. Population expanded rapidly, and many old buildings were torn down to make way for new housing projects. Many of Denver's finest buildings of the frontier era were demolished, such as the Tabor Opera House, as the city has expanded upward and outward and acquired new lands for buildings and parking lots. | |||

The early 1980s brought a bust, especially in computers, electronics and minerals. But Denver bounced back and envisioned even more elaborate projects, such as the largest and most advanced airport in the world. | |||

===Race and ethnic politics=== | |||

Federico Peña (1983-1991) became the city's first [[Latino history|Latino mayor]] in 1983. One of his central campaign messages was a promise of inclusiveness targeted at minorities. His promises of diverse minority appointments represented a stark contrast from prior administration policies. Latino turnout reached 73% in 1983, a striking contrast to the usually low Latino rates elsewhere. In 1991, at a time the city was 12% Black and 20% Latino, Wellington Webb (1991-2003) won a stunning come-from-behind victory as the city's first black mayor. The Hispanic and Black minority communities supported each other's candidates at the 75-85% levels.<ref>Karen M. Kaufmann, "Black and Latino Voters in Denver: Responses to Each Other's Political Leadership." ''Political Science Quarterly'' 2003 118(1): 107-125. ISSN: 0032-3195 Fulltext: [[Ebsco]]</ref> | |||

From the 1930s through the 1970s, racial discrimination was pervasive in Denver's housing, education, and public policy. Much of this discrimination continued informally despite federal and state laws aimed at integration. Before the mid 1960s, Blacks lived east of the central business district in a neighborhood known as Five Points, while Latinos traditionally occupied an area just west of the central business district. There was little integration. Forced busing to achieve integration became the central issue in the school board election in May, 1969; a record number of voters turned out to defeat incumbent board members favoring the busing plan. Because there was deliberate segregation of Park Hill neighborhood schools, the Federal courts ordered the entire Denver Public School system liable to enforced desegregation in a landmark 1972 case, ''Keyes v. Denver Public School District No. 1''; many white families moved to the suburbs in response.<ref> For details see "Keyes v. School District No. 1 - Further Readings" at [http://law.jrank.org/pages/13362/Keyes-v-School-District-No-1.html]</ref> Mayor Webb systematically reached out to the white business community, promoting downtown economic development and major projects such as the world-class new airport, Coors Field, and a new convention center. During his administrations, municipal employment, public schools, police accountability, and affordable housing worsened, for Denver's poor and working-class neighborhoods.<ref> Hermon George, Jr. "Community Development and the Politics of Deracialization: The Case Of Denver, Colorado, 1991-2003." ''Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science'' 2004 594: 143-157. ISSN: 0002-7162</ref> Businessman John Hickenlooper and former petroleum geologist was elected mayor in 2003 and reelected in 2007 with 87% of the vote. | |||

==Sports== | ==Sports== | ||

In professional football the Denver Broncos have played in six super bowls and won two. Voters in 1998 raised $270 million in taxes to build the $360 million Invesco Field at Mile High, a new football stadium. In 2001 it joined Coors Field, which opened for Major League Baseball's Colorado Rockies in 1995, and the Pepsi Center, which opened as the new home of the NHL Colorado Avalanche and the NBA Denver Nuggets in October 1999. Denver's Lower Downtown district, close to the sports and culture venues, has been attracting new residents and businesses to the downtown area. | In professional football the Denver Broncos have played in six super bowls and won two. Voters in 1998 raised $270 million in taxes to build the $360 million Invesco Field at Mile High, a new football stadium. In 2001 it joined Coors Field, which opened for Major League Baseball's Colorado Rockies in 1995, and the Pepsi Center, which opened as the new home of the NHL Colorado Avalanche and the NBA Denver Nuggets in October 1999. Denver's Lower Downtown district, close to the sports and culture venues, has been attracting new residents and businesses to the downtown area. | ||

The first baseball park was Broadway Grounds, where baseball games were being played by 1862. Some early baseball parks were located in the middle of local horse racing tracks. Broadway Park was the home of Denver's first professional teams for about thirty years, into the 1910's. Merchants Park was built in 1922 as the home of the Denver Bears and of the Denver Post Baseball Tournament. When the Denver Bears team was revived after World War II, a replacement for the aging Merchants Park was needed, and Bears Stadium, later renamed Mile High Stadium, was built in 1948. Coors Field, opened in 1993, is the latest Denver baseball field. | |||

Denver made the winning bid to host the 1976 Winter Olympics, but in 1972 a coalition of low-tax advocates and environmentalists rallied and rejected the proposed $5 million state funding, so the games were moved to Austria. The "no" campaign propelled Dick Lamm into the governorship in 1974.<ref> for details see John Sanko, "Colorado only state ever to turn down Olympics," ''Rocky Mountain News'' October 12, 1999 at [http://www.denver-rmn.com/millennium/1012stone.shtml]</ref> | |||

==References== | |||

{{reflist|2}}[[Category:Suggestion Bot Tag]] | |||

< | |||

Latest revision as of 12:03, 6 August 2024

Denver, Colorado is a rapidly growing city of 715,522 people[1] and the capital of Colorado. The metropolitan area has more than 3 million people. The city is located close to the Rocky Mountains at an elevation of about 5,280′, and is thus sometimes called the Mile High City. Denver is a federal regional government center and has the highest concentration of U.S. offices outside Washington, D.C.. The metropolitan area is a hub of financial services, aviation, outdoor recreation, energy, and technology.

Geography

The city itself covers 107 square miles (277 sq km), 5,280 feet (1,610 meters); on average about one mile above sea level, it is called the Mile High City. Winding through Denver are the South Platte River and Cherry Creek. The Rockies provide a spectacular backdrop for the city, with Mount Blue Sky clearly visible on many days, a peak over 14,000 feet high.

Denver is a spacious city of parks, tree-lined streets, broad avenues, old buildings, and modern skyscrapers. Its climate is mild and dry, primarily because the Rockies divert moisture-bearing winds away from the area. Formerly known for its clear sky, it was long a destination for people suffering from tuberculosis. Since 1950, however, exhaust fumes from automobiles and trucks has caused serious air pollution, but since the 1970s an emission testing and registration program coupled with modern vehicles has greatly reduced per capita vehicle air pollution. The average temperature in July, the warmest month, is 73°F (23°C), and the average temperature in January, the coldest month, is 28.5°F. (-2°C). Annual precipitation is only 15 inches (380 mm), and the city has an average of 250 clear or partly cloudy days a year. The sunshine makes it a very popular tourist destination.

Demography

The city's population was 715,522 in 2020. The Denver–Aurora–Boulder Combined Statistical Area had an estimated 2013 population of 3,277,309 and ranked as the 18th most populous U.S. metropolitan area. Denver is the most populous city within a radius centered in the city and of 550-mile (890 km) magnitude.

Minority communities in Denver include a rapidly growing Latino population chiefly of Mexican ancestry.

Suburban Aurora, founded in 1891, exploded in population after 1990, reaching 386,000 in 2020. Nearby Boulder is known both for research, high technology, and liberal politics.

The first Chinese settlers arrived in 1869; two Chinatowns emerged, one a commercial area, the other a residential ghetto. The Chinese population peaked at 1000 in, then declined to 100 in 1940. In the 1950s urban renewal projects demolished the Chinatowns. A new wave of 15,000 highly educated Chinese arrived after 1965, but they were widely dispersed in the metro area.[2]

Economy

Metro Denver is a major manufacturing center of the western United States. It is also a major market for the ranch products (especially beef) of the surrounding area and a gateway for skiers headed to the nearby Rockies.

Semiconductors is the top export category, growing 70% (statewide) from $763 million in 2005, to $1.3 billion in 2006. Other top exports are Computers and Peripherals ($937 million), and Office Machine Components ($657 million). The state's exports were $8.0 billion in 2006; the largest trading partners were Canada ($1.85 billion), Mexico ($1.02 billion), China ($800 million), Taiwan ($707 million), and Japan ($400 million). Denver is home to 32 foreign consulates. Six are staffed by career diplomats from the countries of Guatemala, Japan, Mexico, Peru, Canada and the United Kingdom. The consulates provide information and service regarding international trade promotion, tourism, and cultural exchange.

Employment growth in Metro Denver has outpaced the nation since January 2005. Metro Denver added 26,000 jobs in 2006 for an estimated gain of 1.9%; growth in 2007 will be about 1.6%. All sectors added jobs in 2006 except for the Information sector, which has struggled with losses for six consecutive years. The largest increases were in Natural Resources, Mining & Construction (+4.6%), Transportation, Warehousing & Utilities (+3.2%), and Professional & Business Services (+3.1%) sectors.

Transportation

Denver was at a disadvantage in the 19th century because the transcontinental routes ran 200 miles north of the city, through Cheyenne, Wyoming, which became the primary way station for wagon trains, stage lines, and rail lines passing through the northern Rockies. Pilots at first preferred Cheyenne, and it won the first round of competition when the US Post Office decided to fly mail through Wyoming in 1920. Denver business leaders never stopped competing, however, and struggled to get a share of the traffic. By the mid-1930s they convinced some passenger airlines to move their operations to Colorado. After World War II, Denver wrested full control of Rocky Mountain air traffic from Cheyenne, making the city's Stapleton airport the major regional hub.[3]

Denver International Airport (DIA) is one of the world's ten busiest facilities and is the hub for United and Frontier airlines. DIA has four north-south runways and two east-west runways. The concourses and Jeppesen Terminal (with its Teflon-coated fiberglass roof) are in the center of the airfield. 95 airlines operated 1175 passenger flights daily in 2006, with 130,000 passengers a day. The airport is operating close to capacity and plans to spend $1 billion through 2013 on its concourses, concession areas, security checkpoints, parking lots and baggage system.[4] There are numerous flights to Mexico and Canada, and three to Europe. 44% of the passengers are making connections in Denver; Los Angeles is the chief point of origin. DIA replaced inner-city Stapleton International Airport (1929-1995). Once open range country, the area near DIA is undergoing rapid construction of homes, hotels and warehouses.

The Valley Highway, now Interstate I-25, had been planned since 1938; it was delayed by the war but construction began in 1948. By the time of its opening in 1958, the 11-mile north-south "superhighway" required 57 bridges, 17 interchanges, and a relocation of two-thirds of a mile of the South Platte River. The Valley Highway, by running through metropolitan Denver, made the city more accessible, led to a commercial boom for Denver and opened up the suburbs to development.

In 2006 the $1.67 billion T-REX project widened Interstates 25 and I-225 and added 19 miles of light rail connecting Metro Denver's two largest employment centers: The Central Business District and the Denver Tech Center.

Downtown

At the center of downtown is the Denver Civic Center, a 40 acre (16-hectare) complex of parks and government buildings. At opposite ends of the Center are the City-County Building and the State Capitol. The Capitol is 272 feet (83 meters) high and has a dome covered with local gold. By the time the capitol was completed in 1900 (at 170% over budget) the building—a difficult-to-maintain hodgepodge of dirt-collecting nooks and crannies, grumblers said—was instantly too small. In the 21st century the debate is whether Colorado's aging yet "most important building" deserves a mere nip and tuck or an extreme makeover.[5] Nearby are the Art Museum, and the Denver Public Library (which contains more than one million volumes, especially famous for its research collection in western history). The United States Mint makes half the nation's coins. Until the 1950s buildings in Denver could not be higher than 12 stories, but since then a number of skyscrapers more than 40 stories tall have been added to the city skyline, including the Arco Tower, Anaconda Tower, Great West Plaza, and the Amoco Building. During the 1970s an extensive urban renewal program was undertaken in downtown Denver, leading to the creation of a three-square block convention center and an elaborate theater complex, the Denver Center for the Performing Arts.

Medical

Across the western landscape of the United States, health was a natural resource, mined and sold by late-19th- and 20th-century town boosters and physicians to those afflicted with such chronic pulmonary illnesses as tuberculosis and asthma. Denver was especially important as a destination and the city became the largest medical center for the mountain states by 1900.[6] Religious and ethnic groups established the most important hospitals. St. Luke's Hospital was established by the Episcopal Church in 1881; Presbyterian Hospital opened in 1926. Both operated nursing schools . In 1992 St. Luke's merged with Presbyterian Hospital, which subsequently merged with others to form the HealthONE hospital system.[7] The Denver Homeopathic Hospital opened in 1894 to offer alternatives to the medical practices of "allopathic" medicine, the mainstream treatments of the day. Friction arose among the homeopathic physicians, and the hospital closed in 1909.[8] During 1906-15, wealthy women established The Children's Hospital of Denver, focusing its work on middle-class health concerns. The Swedish National Sanatorium was established in 1905 by the Swedish community, as a national tuberculosis sanatorium. It was reorganized in 1956 and later became the Swedish Medical Center. [9] Seraphine Pisko was first woman to head a major Jewish hospital when she was appointed in 1911 as secretary of Denver's National Jewish Hospital for Consumptives, Pisko skillfully and efficiently managed the institution, while advancing a personalized and nurturing philosophy of charity in contrast to efforts to centralize fund-raising and administration. After World War II the Jewish National Home for Asthmatic Children became the Children's Asthma Research Institute and Hospital. To the dismay of the city of Denver, the University of Colorado Medical School and associated hospitals left the city in 2007, taking 30,000 high-paying jobs, for a huge new campus in Aurora centered on the former Fitzsimons Army Medical Center. It solidified the Denver Metro Area as the premier medical center in a thousand mile radius, but brought into debate the state's sharply reduced budget for medical education and higher education generally.

History

Denver was started during the turbulent Pikes Peak gold rush of 1859-1860, when thousands walked across the plains in search of wealth. Two small settlements, Denver City and Auraria, were consolidated in 1860; the city was named after the governor of Kansas. Population reached 4700 in 1860 and remained the same a decade later. The first city hall was built on stilts in the middle of a stream. Boom and bust characterized the early years, 1859-1870. In 1863 a fire destroyed much of Denver, and the next year a flash flood destroyed the precariously built city hall on stilts.

In 1861 Colorado became a territory, with a governor appointed by President Abraham Lincoln. In 1867 Denver became the capital. The major obstacles to the city's growth were its isolation from the East and the Midwest and the lack of a stable income-producing economy. The Indian wars on the plains and heavy winter snowstorms east of the city were a constant threat to the connections with Kansas and points eastward. In 1863 the telegraph arrived. The coming of the railroads integrated the city further with the rest of the nation. In 1870 the Denver Pacific Railroad north to Cheyenne, Wyoming, linked into the transcontinental Union Pacific Railroad, while the Kansas Pacific Railroad linked across the plains to Kansas City. The Denver and Rio Grande Railroad south to Pueblo opened in 1871, thus making Denver the hub of all mining and ranching areas in Colorado; the population hit 36,000 in 1880, augmented by a steady influx of German, Irish and English workers and craftsmen.

The city provided lavishly for the lusts of the rich miners visiting the city. There was a range of bawdy houses to fit every pocketbook, from the sumptuous quarters of renowned madams such as Mattie Silks and Jenny Rogers to the most squalid "cribs" located a few blocks farther north along Market Street. Gambling flourished as sharp-eyed bunco artists exploited every chance to separate miners from their hard-earned gold. Edward Chase ran scrupulously honest games in several elegant establishments and regularly entertained many of Denver's most influential leaders. By 1880 Denver's vice district ranked only slightly behind San Francisco's Barbary Coast and New Orleans's Storyville. Most of the city's seamiest attractions were within a few steps of Union Station, but newsstands sold guidebooks that provided additional addresses. Sin was good for business; visitors spent lavishly, then left town. As long as madams conducted their business discreetly, and "crib girls" did not advertise their availability too crudely, authorities took their bribes and looked the other way. Occasional cleanups and cracked downs satisfied the demands for reform.[10]

In legitimate entertainment, music stood high, beginning with the Apollo Hall in 1859. The Denver Theatre, home of the city's first opera performance in 1864, the Tabor Grand Opera House (1881)and the Broadway Theatre (1890-1955) brought in internationally renown performers. Many other theaters were built, most of which did not last very long. Denver churches were also important venues for music performances in the last half of the 19th century.[11] There were orchestras playing classical music as early as 1892, as well as two rival orchestras in the first decade of the 20th century. The Denver Symphony Orchestra was the first professional group, debuting in November 1934 under Horace E. Tureman. Its reputation grew, especially under the conductorship of Saul Caston, who led the orchestra from 1945 through perhaps its finest years until 1963.[12]

In the 1880s silver was discovered in the nearby mountains, leading Denver to a new surge of gaudiness and opulence, typified by Tabor's fancy opera house. The silver madness was as economically unstable as the gold rush 20 years before. The 10-story Brown Palace Hotel in 1893, designed by noted local architect Frank Edbrooke. In 1893 financial panic swept the nation, and the silver boom collapsed. By this time, however, the city's economy had a more stable base rooted in the agriculture of the surrounding area.

Between 1870 and 1890 the city's population increased from less than 5,000 to over 100,000. In the 1880s entrepreneurs who had recently installed water supplies, sewers, trolley lines, and railroad connections moved to obtain urban gas and electric franchises. Since Denver was growing rapidly and unpredictably, franchise holders soon found themselves at the mercy of demand for costly extension of services to the outlying areas at rates no higher than those for the central city. Henry Doherty met the challenge by offering customers a three-level rate structure whose effect was to keep basic rates uniform throughout cities and suburbs and to give lower rates to higher volume (wealthier) customers. Doherty hired a large sales force to increase consumer demand for gas and electricity by replacing old kerosene lamps with gas light, and selling electric irons and gas water heaters door to door, promoting their virtues of cleanliness, comfort, convenience and economy.[13] Denver's Myron W. Reed was the leading Christian socialist in the American West in the last two decades of the nineteenth century. He came to the city in 1884 as pastor of the affluent First Congregational Church. Christian socialism, for Reed, meant that the state should manage production and instill cooperation to provide what he called "the comfortable life" for all. He was a leader in the city's Charity Organization Society, even while questioning that organization's efforts to distinguish the "worthy" from the "unworthy" poor. Reed spoke out for the rights of labor unions and was voted out of his pulpit during the bitter 1894 strike at Cripple Creek. He ran for Congress as a Democrat in 1886 and worked for Colorado's Populist party in the 1890s. A former abolitionist Reed spoke out for African American and Native American rights while denouncing Chinese and eastern European immigrants as dependent tools of corporations who were lowering "American" standards of living.[14]

Progressive era

The city doubled between 1900 and 1920, reaching 256,000 population. Growth slowed somewhat, as the total in 1940 was 322,000, with few suburbs as yet.

Local boosters created the National Stock Growers Conventions in 1898 and 1899. The National Western Stock Show began in 1907 as an annual event attracting cattlemen from a wide region. The Progressive Era brought an Efficiency Movement, typified in 1902 when the city and Denver County were made coextensive;[15] Denver pioneered the juvenile court movement under Judge Ben Lindsey (1869-1943). While serving as a law clerk in Denver, Lindsey became concerned with the plight of children who were imprisoned for minor offenses. As a lawyer he secured a court appointment as guardian of orphans and other wards of the county. Later, as a judge he launched a crusade that pioneered reforms and established a juvenile court system that gained him national and international acclaim.[16] Mayor Robert Speer was a prominent progressive who gave the city world leadership in building parks. Boasting itself the "Queen City of the Plains," Denver hosted the Democratic National Convention in 1908, then waited 100 years for its return.

Famed evangelist and ardent prohibitionist Billy Sunday came to Denver in September and October 1914 to speak on behalf of the proposed state prohibition amendment. His revival lasted about two months, held in a specially built tabernacle near Capitol Hill. Sunday spoke to a total of 60,000 pietistic Protestants. In spite of this, the prohibition amendment was defeated in Denver, a Catholic wet stronghold; however it passed statewide; the "dry" vote was almost three times as great as that of a similar referendum held in 1912 as Colorado made saloons illegal.[17]

Women suffrage came early, in 1893, led by married middle class women who organized first for prohibition and then for suffrage, with the goal of upholding republican citizenship for women and purifying society. The Denver Fortnighly Club played a major role. Caroline Nichols Churchill, edited and published the Colorado Antelope, subsequently the Queen Bee, beginning in 1879 and boasted that she and her journal played a crucial role in the passage of the referendum in 1893 that granted the vote to women in Colorado. There was a strained relationship between the radical and eccentric Churchill and the mainstream women, as Churchill was a confrontational and outspoken proponent of the equal rights of minority ethnic groups.[18]

The nation saw a wave of strikes in 1919, as labor unions tried to preserve their wartime gains. The Amalgamated Association of Street and Railway Employees of America led a strike against the Denver Tramway Company in 1920. Rioting broke out before US Army troops were called in; seven people were killed by gunfire, none of them strikers or rioters, and fifty people were injured. The army troops stayed in Denver for a month. The union lost the strike, two-thirds of its workers lost their jobs, and organized labor was weakened severely in Denver. The Tramway Company offset its financial losses from the strike through a fare raise and survived the crisis.[19]

The KKK was briefly active in the mid-1920s. The membership a cross-section of the city's Protestants (except that the elite did not join). White Protestant men from all socioeconomic levels joined to save their communities and homes from so-called disruptive groups: Catholics, Jews, blacks, immigrants, and law violators.[20]

During the 10 years Robert Speer served as mayor (1904-1912, 1916-1918), voters approved bond issues enabling the implementation of "City Beautiful" plans that brought Denver to the forefront of the movement nationally. Using political coalitions and reform rhetoric, urban plans, and architectural projects, Speer used City Beautiful ideals to build a power base. Opposition came from more "radically" Progressives. The roots of City Beautiful reform were in the park movement of the 1880s and the concomitant modifications in municipal government that gave officials the power to direct urban development. Speer brought nationally recognized designers including Charles Mulford Robinson, George Kessler, Frederick MacMonnies, and Edward Bennett to Denver as consultants and developed a series of City Beautiful projects that included a municipal auditorium, a bath house, memorial sculpture and pavilions, a civic center, and intra- and extra-urban parks and parkways.[21] When the Dutch-born architect Saco Rienk DeBoer arrived in Denver in 1908, he found a city mostly devoid of landscaping. Appointed as landscape architect for the city DeBoer's first assignment was to create Sunken Gardens Park. He also planted trees along several Denver streets, experimenting over the years with different varieties to find the trees most suitable to Denver's climate. His landscaping of the city parks also accommodated the automobile. In 1925, DeBoer was appointed to Denver's first zoning commission, and he planned the landscaping of the new municipal airport in 1929. His ideas for residential landscaping were carried out in Lakewood and the Cherry Hills area, and his ideas for commercial plazas were later used as models for the shopping centers of the 1950s. He also drew the plans for the City Park botanical gardens as well as the newer ones several years later.[22]

World War II and after

Up until World War II, Denver's economy was dependent mainly on the processing and shipping of minerals and ranch products, especially beef and lamb. During the war and in the years following, specialized industries were introduced into the city, making it a major manufacturing center. Lowry Air Force Base, Fitzsimons Army Hospital, and Fort Logan were major installations, as defense dollars spurred the local economy. Rocky Mountain Arsenal made munitions. Denverites participated in civil defense preparedness, rationing, and price controls, and sent 45,000 locals to the armed services.[23] See also World War II, Homefront, U.S.

The wartime housing shortage led to a postwar construction boom, as Denver was a magnet for many of the servicemen who had been stationed nearby in the war. The population surged in the city and spilled into farmlands that became instant suburbs. A change in the political and financial climate also brought a more progressive leadership to Denver, as the old families were pushed aside by newly arrived entrepreneurs. Population expanded rapidly, and many old buildings were torn down to make way for new housing projects. Many of Denver's finest buildings of the frontier era were demolished, such as the Tabor Opera House, as the city has expanded upward and outward and acquired new lands for buildings and parking lots.

The early 1980s brought a bust, especially in computers, electronics and minerals. But Denver bounced back and envisioned even more elaborate projects, such as the largest and most advanced airport in the world.

Race and ethnic politics

Federico Peña (1983-1991) became the city's first Latino mayor in 1983. One of his central campaign messages was a promise of inclusiveness targeted at minorities. His promises of diverse minority appointments represented a stark contrast from prior administration policies. Latino turnout reached 73% in 1983, a striking contrast to the usually low Latino rates elsewhere. In 1991, at a time the city was 12% Black and 20% Latino, Wellington Webb (1991-2003) won a stunning come-from-behind victory as the city's first black mayor. The Hispanic and Black minority communities supported each other's candidates at the 75-85% levels.[24]

From the 1930s through the 1970s, racial discrimination was pervasive in Denver's housing, education, and public policy. Much of this discrimination continued informally despite federal and state laws aimed at integration. Before the mid 1960s, Blacks lived east of the central business district in a neighborhood known as Five Points, while Latinos traditionally occupied an area just west of the central business district. There was little integration. Forced busing to achieve integration became the central issue in the school board election in May, 1969; a record number of voters turned out to defeat incumbent board members favoring the busing plan. Because there was deliberate segregation of Park Hill neighborhood schools, the Federal courts ordered the entire Denver Public School system liable to enforced desegregation in a landmark 1972 case, Keyes v. Denver Public School District No. 1; many white families moved to the suburbs in response.[25] Mayor Webb systematically reached out to the white business community, promoting downtown economic development and major projects such as the world-class new airport, Coors Field, and a new convention center. During his administrations, municipal employment, public schools, police accountability, and affordable housing worsened, for Denver's poor and working-class neighborhoods.[26] Businessman John Hickenlooper and former petroleum geologist was elected mayor in 2003 and reelected in 2007 with 87% of the vote.

Sports

In professional football the Denver Broncos have played in six super bowls and won two. Voters in 1998 raised $270 million in taxes to build the $360 million Invesco Field at Mile High, a new football stadium. In 2001 it joined Coors Field, which opened for Major League Baseball's Colorado Rockies in 1995, and the Pepsi Center, which opened as the new home of the NHL Colorado Avalanche and the NBA Denver Nuggets in October 1999. Denver's Lower Downtown district, close to the sports and culture venues, has been attracting new residents and businesses to the downtown area.

The first baseball park was Broadway Grounds, where baseball games were being played by 1862. Some early baseball parks were located in the middle of local horse racing tracks. Broadway Park was the home of Denver's first professional teams for about thirty years, into the 1910's. Merchants Park was built in 1922 as the home of the Denver Bears and of the Denver Post Baseball Tournament. When the Denver Bears team was revived after World War II, a replacement for the aging Merchants Park was needed, and Bears Stadium, later renamed Mile High Stadium, was built in 1948. Coors Field, opened in 1993, is the latest Denver baseball field.

Denver made the winning bid to host the 1976 Winter Olympics, but in 1972 a coalition of low-tax advocates and environmentalists rallied and rejected the proposed $5 million state funding, so the games were moved to Austria. The "no" campaign propelled Dick Lamm into the governorship in 1974.[27]

References

- ↑ 715,522 was the official population as of the 2020 census.

- ↑ William Wei, "History and Memory: the Story of Denver's Chinatown." Colorado Heritage 2002 (Aut): 2-13. Issn: 0272-9377

- ↑ Roger D. Launius, and Jessie L. Embry, "Cheyenne Versus Denver: City Rivalry and the Quest for Transcontinental Air Routes." Annals of Wyoming 1996 68(3): 8-23. Issn: 1086-7368

- ↑ See Chris Walsh, "DIA bursting at the seams," Rocky Mountain News September 29, 2007 at [1]

- ↑ Derek R. Everett, The Colorado State Capitol: History, Politics, Preservation. 2005.

- ↑ Gregg Mitman, "Geographies of Hope: Mining the Frontiers of Health in Denver and Beyond, 1870-1965." Osiris 2004 19: 93-111. Issn: 0369-7827

- ↑ Rebecca Hunt, "Healers on the Hill: St. Luke's and Presbyterian Hospitals of Denver." Colorado Heritage 2005 (Sum): 2-17. Issn: 0272-9377

- ↑ Steve Grinstead, "Alternative Healing At The Crossroads: Denver's Homeopathic Hospital Succumbs To Modern Medicine." Colorado Heritage 2005 (Sum): 18-29. Issn: 0272-9377

- ↑ Rebecca Hunt, "Swedish National Sanatorium: Building Community in a Swedish-American Tuberculosis Sanatorium, 1905-59." Colorado Heritage 2005 (Sum): 30-46. ISSN: 0272-9377

- ↑ Clark Secrest. Hell's Belles: Prostitution, Vice, and Crime in Early Denver, with a Biography of Sam Howe, Frontier Lawman. 2nd ed 2002, heavily illustrated.

- ↑ Henry Miles, "Where Music Dwells: Denver's Earliest Concert Spaces." Colorado Heritage 2002 (Sum): 32-46.

- ↑ James Michael Bailey, "Notes of Turmoil: Sixty Years of Denver's Symphony Orchestras." Colorado Heritage 1992 (Aut): 33-47.

- ↑ Mark H. Rose, Cities of Light and Heat: Domesticating Gas and Electricity in Urban America 1995.

- ↑ James A. Denton, Rocky Mountain Radical: Myron W. Reed, Christian Socialist. 1997.

- ↑ Since then both the city and the county have been governed by a nonpartisan mayor and nine-member council.

- ↑ D'Ann Campbell, "Judge Ben Lindsey and the Juvenile Court Movement, 1901-1904." Arizona and the West 1976 18(1): 5-20. Issn: 0004-1408; also [2]

- ↑ David A. Baldwin, "When Billy Sunday 'Saved' Colorado: That Old-time Religion and the 1914 Prohibition Amendment." Colorado Heritage 1990 (2): 34-44.

- ↑ Jennifer A. Thompson, "From Travel Writer to Newspaper Editor: Caroline Churchill and the Development of Her Political Ideology Within the Public Sphere." Frontiers 1999 20(3): 42-63. Issn: 0160-9009 Fulltext: in Jstor

- ↑ Stephen J. Leonard, "Bloody August: The Denver Tramway Strike of 1920." Colorado Heritage 1995 (Sum): 18-31.

- ↑ Robert A. Goldberg, "Beneath the Hood and Robe: a Socioeconomic Analysis of Ku Klux Klan Membership in Denver, Colorado, 1921-1925." Western Historical Quarterly 1980 11(2): 181-198. Issn: 0043-3810 Fulltext: in Jstor

- ↑ See Carol McMichael Reese, "The Politician and the City: Urban Form and City Beautiful Rhetoric in Progressive Era Denver." PhD dissertation U. of Texas, Austin 1992.

- ↑ Joyce Summers, "One Man's Vision: Saco Rienk Deboer, Denver Landscape Architect" Colorado Heritage 1988 (2): 28-42.

- ↑ Stephen J. Leonard, "Denver at War: the Home Front in World War II" Colorado Heritage 1987 (4): 30-39.

- ↑ Karen M. Kaufmann, "Black and Latino Voters in Denver: Responses to Each Other's Political Leadership." Political Science Quarterly 2003 118(1): 107-125. ISSN: 0032-3195 Fulltext: Ebsco

- ↑ For details see "Keyes v. School District No. 1 - Further Readings" at [3]

- ↑ Hermon George, Jr. "Community Development and the Politics of Deracialization: The Case Of Denver, Colorado, 1991-2003." Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 2004 594: 143-157. ISSN: 0002-7162

- ↑ for details see John Sanko, "Colorado only state ever to turn down Olympics," Rocky Mountain News October 12, 1999 at [4]