Moving panorama: Difference between revisions

imported>Russell Potter (→Subject Matter: expanding this history) |

Pat Palmer (talk | contribs) |

||

| (45 intermediate revisions by 9 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{subpages}} | |||

The ''' | |||

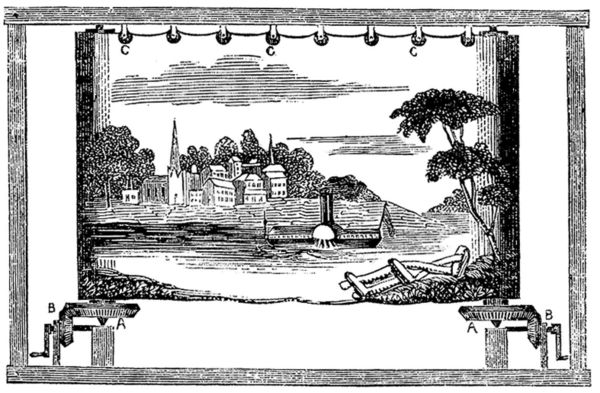

{{Image|Moving_panorama.jpg|right|600px|Diagram showing the mechanism of a moving panorama, from ''Scientific American'', 1848}} | |||

The '''moving panorama''' was a popular form of visual entertainment in the nineteenth century. A relative more in concept than design to the [[Panoramic painting]], it proved to be more durable than its fixed and immense cousin. Unlike 360 degree paintings that coralled their audiences into a constrained space, the moving panorama allowed a sense of limitless travel, and made the audience, rather than the image, seem to ''move''. Such paintings were not panoramas in the truest sense, but rather contiguous views of passing scenery, as if seen from a boat or a train window. Installed on immense spools, they were scrolled past the audience behind a cut-out drop-scene or proscenium which hid the mechanism from public view. In contrast to [[Panoramic painting|fixed panoramas]], the moving panorama almost always had a narrator, styled as its "Delineator" or "Professor", who described the scenes as they passed and added to the drama of the events depicted. One of the most successful of these delineators was [[John Banvard]], whose panorama of a trip up (and down) the [[Mississippi River]] had such a successful world tour that the profits enabled him to build an immense mansion, lampooned as "Banvard's Folly", built in imitation of [[Windsor Castle]] in the hinterlands of [[New Jersey (U.S. state)|New Jersey]].<ref>see ''Banvard's Folly: Thirteen Tales of People Who Didn't Change the World'', by Paul S. Collins, ISBN 0312300336</ref> The earliest moving panoramas were shown in the [[United Kingdom]] by the [[Edinburgh]] firm of "Messrs. Marshall" in the 1820s; by mid-century, dozens of showmen criss-crossed the provinces, and the form had spread to the [[United States of America]] and even to [[Australia]]. | |||

==Subject Matter== | ==Subject Matter== | ||

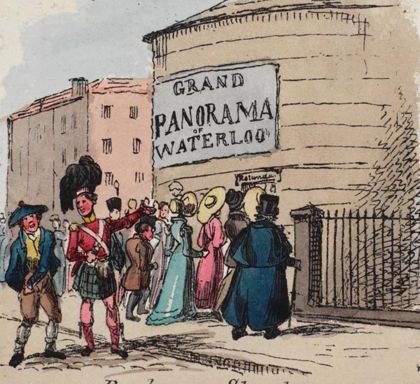

The earliest moving panoramas often depicted public processions, street elevations, and other pedestrian views. The Edinburgh firm of "Messrs. Marshall" enjoyed tremendous success with their views of the Cornation of [[George IV]] in 1823. They also, however, portrayed far more thrilling subjects, such as the infamous "Raft of the Medusa"; their panorama of this event was shown in [[Dublin]] at the same time as [[ | {{Image|Glasgow panoram.jpg|right|420px|Colored print showing the Marshalls' Panorama on Buchanan-Street in Glasgow, circa 1828. Glasgow University Library, Special Collections}} | ||

The earliest moving panoramas often depicted public processions, street elevations, and other pedestrian views. The Edinburgh firm of "Messrs. Marshall" enjoyed tremendous success with their views of the Cornation of [[George IV]] in 1823. They also, however, portrayed far more thrilling subjects, such as the infamous "Raft of the Medusa"; their panorama of this event was shown in [[Dublin]] at the same time as [[Théodore Géricault|Géricault's]] great canvas of the same scene, as was so much more successful that the fellow showing Géricault's canvas was forced to close up shop and cart it back to [[London, United Kingdom|London]]. The Marshalls continued in business throughout the period from 1824-1850, with panoramas of the [[Battle of Bannockburn]], Sir [[John Ross]]'s Arctic Voyages, views of [[New York, New York]], and numerous other subjects. Their panoramas were also noted for being "peristrephic" -- that is, they were shown, not on a ''flat'' surface, but on a concave semicircular wall, which gave an impression of depth as well as movement; for such exhibitions the Marshalls erected purpose-built rotundas in [[Glasgow]] and [[Edinburgh]]. The exact mechanism used is still imperfectly understood. | |||

At mid-century, the form enjoyed a tremendous revival of interest. | {{Image|Panorama handbill.gif|left|350px|Handbill for a Moving Panorama of a Voyage to Europe, c. 1880}} | ||

At mid-century, the form enjoyed a tremendous revival of interest. Well suited to the depiction of travel, since the scrolling of the canvas corresponded readily with the traverse of a linear landscape, moving panoramas of ocean voyages, train excursions, and even (in vertical form) the ascent of [[Mont Blanc]] drew tens of thousands of spectators on both sides of the [[Atlantic ocean|Atlantic]]. In the United Kingdom in the 1850s, besides Banvard's Mississippi panorama, panoramas of voyages to [[New Zealand]] and the [[Holy Land]] were popular, as were depictions of the ''Overland Mail to India'', which was the subject of no fewer than three moving panoramas. Voyages across the [[Atlantic ocean|Atlantic]] were a perpetual subject (see the handbill at left), as were crossings of [[North America]] during the period immediately following the [[California Gold Rush]]. The Great Lakes framed a number of panoramas, including one, the ''Nine-Mile Mirror'', which claimed to actually ''be'' nine miles in length (the weight of such a canvas would have prohibited its transport or easy display). One of the most durable subjects proved to be the exploration of the [[Arctic|Arctic regions]], which was the subject of no fewer than a ''dozen'' moving panoramas in the period 1849-1859 alone.<ref>Russell A. Potter, ''Arctic Spectacles: The Frozen North in Visual Culture, 1818-1875'' (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2007)</ref> Wars were always a popular subject; several panoramas in the late 1850's depicted scenes from the [[Crimean War]] and the [[Sepoy Rebellion]] in India, and the latter nineteenth century saw hundreds of competing panoramas of the [[American Civil War]]. A wide variety of other subjects, from the [[Bible]] to [[Pilgrim's Progress]] to scenes from popular legends and romance, were also depicted in moving panoramas, which in many senses functioned in their day much as [[television]] did in the [[twentieth century]]. | |||

==Popularity== | ==Popularity== | ||

At the peak of its success in the mid-nineteenth century, the moving panorama was quite possibly the most popular entertainment in the world, with hundreds of panoramas constantly touring the countryside | At the peak of its success in the mid-nineteenth century, the moving panorama was quite possibly the most popular entertainment in the world, with hundreds of panoramas constantly touring major cities as well as the countryside, all around the world. The smaller panoramas could be hauled by horse and wagon, and the expansion of railway service in countries such as the United Kingdom and the United States opened new markets to traveling panoramists. The larger firms, such as George K. Goodwin's of [[Boston, Massachusetts]], managed many simultaneous shows, which travelled separately under subsidiary showman, while smaller firms managed only one panorama at a time. The trade was so extensive that both [[New York, New York|New York]] and [[Philadelphia, Pennsylvania|Philadelphia]] had two firms each which specialized in painting panoramas to order. Careers could be made in the field by anyone who had a talent for dramatizing the moving scenery as it passed, and well-known public figures with a gift for stentorian speech -- among them actors, lawyers, and state legislators -- often spent some time in this employment. | ||

One typical such figure, [[Rufus C. Somerby]], spent more than twenty years in the | One typical such figure, [[Rufus C. Somerby]], spent more than twenty years in the mid western states showing panoramas managed by Goodwin. He served as the "delineator" (narrator) and his wife, the "musical accompanist," played the piano; over the years, they shared a bill with all manner of acts from glass harmonica players and "facial contortionists" to mechanical orchestras and trained monkeys. He was associated with several [[Arctic]] panoramas, as well as a panorama of "[[John Milton|Milton]]'s Pandemonium" and claimed that, at various times, his audience included [[Abraham Lincoln]] and [[Ulysses S. Grant]].<ref>Rufus C. Somerby, as "Dr. Judd," "The Old Panorama", ''The Billboard'', December 5 1903, pp. 25,26.</ref> | ||

[[Mark Twain]], in "The Entertaining History of the Scriptural Panoramist" (1866), gives a fair idea of the audience for a panorama of Bible scenes in mid-century: | [[Mark Twain]], in "The Entertaining History of the Scriptural Panoramist" (1866), gives a fair idea of the audience for a panorama of Bible scenes in mid-century: | ||

::"There was a big audience that night, mostly middle-aged and old people who belonged to the church and took a strong interest in Bible matters, and the balance were pretty much young bucks and heifers -- ''they'' always come out strong on panoramas, you know, because it gives them a chance to taste each other's mugs in the dark."<ref>From ''Sketches New and Old'', Project Gutenberg text, available at http://www.gutenberg.org/etext/3189</ref> | ::"There was a big audience that night, mostly middle-aged and old people who belonged to the church and took a strong interest in Bible matters, and the balance were pretty much young bucks and heifers -- ''they'' always come out strong on panoramas, you know, because it gives them a chance to taste each other's mugs in the dark."<ref>From ''Sketches New and Old'', Project Gutenberg text, available at http://www.gutenberg.org/etext/3189</ref> | ||

Twain's story goes on to relate, with considerable humor, the unhappy experience of this panoramist who, having lost his musical accompanist, unknowingly hires a local drunk to play the piano during the panorama. | Twain's story goes on to relate, with considerable humor, the unhappy experience of this panoramist who, having lost his musical accompanist, unknowingly hires a local drunk to play the piano during the panorama. At the most inappropriate moments, such as the scene of the happy return of the Prodigal Son, the pianist launches into drinking songs, such as "Oh, we'll all get blind drunk, when Johnny comes marching home." Humor aside, the depiction of an evening's entertainment Twain gives is a vivid and engaging one; religious subjects were increasingly common subject for panoramas later in the century, when, facing competition from newer forms of entertainment, they were more often shown in schools and churches than in large public halls. | ||

==Surviving moving panoramas== | ==Surviving moving panoramas== | ||

Few moving panoramas have survived to this day, and conservation issues frequently prevent them from being shown in their original format. The most notable rediscovered moving panorama in the [[United States]] is the [[Grand Moving Panorama of Pilgrim's Progress]], which was discovered after having been forgotten in storage after nearly a century at the [[York Institute]] in [[Saco, Maine]] by Tom Hardiman. | Few moving panoramas have survived to this day, and conservation issues frequently prevent them from being shown in their original format. The most notable rediscovered moving panorama in the [[United States of America]] is the [[Grand Moving Panorama of Pilgrim's Progress]], which was discovered after having been forgotten in storage after nearly a century at the [[York Institute]] in [[Saco, Maine]] by Tom Hardiman. It was found to incorporate designs by many of the leading painters of its day, including [[Jasper Francis Cropsey]], [[Frederic Edwin Church]], and [[Henry Courtney Selous]] (Selous was the in-house painter for the original Barker panorama in London for many years). The [[Peabody-Essex Museum]] in [[Salem]], [[Massachusetts (U.S. state)|Massachusetts]] has Thomas F. Davidson's moving panorama of a Whaling Voyage (1860), and the [[New Bedford Whaling Museum]] in [[New Bedford]], [[Massachusetts (U.S. state)|Massachusetts]] owns Russell & Purrington's panorama of a Whaling Voyage Round the World, though it is currently (2007) no longer on display. A [[Mormon Panorama]] also survives at [[Brigham Young University]]'s Art Museum. | ||

==References== | ==References== | ||

<references/> | <references/> | ||

Revision as of 07:31, 20 April 2024

The moving panorama was a popular form of visual entertainment in the nineteenth century. A relative more in concept than design to the Panoramic painting, it proved to be more durable than its fixed and immense cousin. Unlike 360 degree paintings that coralled their audiences into a constrained space, the moving panorama allowed a sense of limitless travel, and made the audience, rather than the image, seem to move. Such paintings were not panoramas in the truest sense, but rather contiguous views of passing scenery, as if seen from a boat or a train window. Installed on immense spools, they were scrolled past the audience behind a cut-out drop-scene or proscenium which hid the mechanism from public view. In contrast to fixed panoramas, the moving panorama almost always had a narrator, styled as its "Delineator" or "Professor", who described the scenes as they passed and added to the drama of the events depicted. One of the most successful of these delineators was John Banvard, whose panorama of a trip up (and down) the Mississippi River had such a successful world tour that the profits enabled him to build an immense mansion, lampooned as "Banvard's Folly", built in imitation of Windsor Castle in the hinterlands of New Jersey.[1] The earliest moving panoramas were shown in the United Kingdom by the Edinburgh firm of "Messrs. Marshall" in the 1820s; by mid-century, dozens of showmen criss-crossed the provinces, and the form had spread to the United States of America and even to Australia.

Subject Matter

The earliest moving panoramas often depicted public processions, street elevations, and other pedestrian views. The Edinburgh firm of "Messrs. Marshall" enjoyed tremendous success with their views of the Cornation of George IV in 1823. They also, however, portrayed far more thrilling subjects, such as the infamous "Raft of the Medusa"; their panorama of this event was shown in Dublin at the same time as Géricault's great canvas of the same scene, as was so much more successful that the fellow showing Géricault's canvas was forced to close up shop and cart it back to London. The Marshalls continued in business throughout the period from 1824-1850, with panoramas of the Battle of Bannockburn, Sir John Ross's Arctic Voyages, views of New York, New York, and numerous other subjects. Their panoramas were also noted for being "peristrephic" -- that is, they were shown, not on a flat surface, but on a concave semicircular wall, which gave an impression of depth as well as movement; for such exhibitions the Marshalls erected purpose-built rotundas in Glasgow and Edinburgh. The exact mechanism used is still imperfectly understood.

At mid-century, the form enjoyed a tremendous revival of interest. Well suited to the depiction of travel, since the scrolling of the canvas corresponded readily with the traverse of a linear landscape, moving panoramas of ocean voyages, train excursions, and even (in vertical form) the ascent of Mont Blanc drew tens of thousands of spectators on both sides of the Atlantic. In the United Kingdom in the 1850s, besides Banvard's Mississippi panorama, panoramas of voyages to New Zealand and the Holy Land were popular, as were depictions of the Overland Mail to India, which was the subject of no fewer than three moving panoramas. Voyages across the Atlantic were a perpetual subject (see the handbill at left), as were crossings of North America during the period immediately following the California Gold Rush. The Great Lakes framed a number of panoramas, including one, the Nine-Mile Mirror, which claimed to actually be nine miles in length (the weight of such a canvas would have prohibited its transport or easy display). One of the most durable subjects proved to be the exploration of the Arctic regions, which was the subject of no fewer than a dozen moving panoramas in the period 1849-1859 alone.[2] Wars were always a popular subject; several panoramas in the late 1850's depicted scenes from the Crimean War and the Sepoy Rebellion in India, and the latter nineteenth century saw hundreds of competing panoramas of the American Civil War. A wide variety of other subjects, from the Bible to Pilgrim's Progress to scenes from popular legends and romance, were also depicted in moving panoramas, which in many senses functioned in their day much as television did in the twentieth century.

Popularity

At the peak of its success in the mid-nineteenth century, the moving panorama was quite possibly the most popular entertainment in the world, with hundreds of panoramas constantly touring major cities as well as the countryside, all around the world. The smaller panoramas could be hauled by horse and wagon, and the expansion of railway service in countries such as the United Kingdom and the United States opened new markets to traveling panoramists. The larger firms, such as George K. Goodwin's of Boston, Massachusetts, managed many simultaneous shows, which travelled separately under subsidiary showman, while smaller firms managed only one panorama at a time. The trade was so extensive that both New York and Philadelphia had two firms each which specialized in painting panoramas to order. Careers could be made in the field by anyone who had a talent for dramatizing the moving scenery as it passed, and well-known public figures with a gift for stentorian speech -- among them actors, lawyers, and state legislators -- often spent some time in this employment.

One typical such figure, Rufus C. Somerby, spent more than twenty years in the mid western states showing panoramas managed by Goodwin. He served as the "delineator" (narrator) and his wife, the "musical accompanist," played the piano; over the years, they shared a bill with all manner of acts from glass harmonica players and "facial contortionists" to mechanical orchestras and trained monkeys. He was associated with several Arctic panoramas, as well as a panorama of "Milton's Pandemonium" and claimed that, at various times, his audience included Abraham Lincoln and Ulysses S. Grant.[3]

Mark Twain, in "The Entertaining History of the Scriptural Panoramist" (1866), gives a fair idea of the audience for a panorama of Bible scenes in mid-century:

- "There was a big audience that night, mostly middle-aged and old people who belonged to the church and took a strong interest in Bible matters, and the balance were pretty much young bucks and heifers -- they always come out strong on panoramas, you know, because it gives them a chance to taste each other's mugs in the dark."[4]

Twain's story goes on to relate, with considerable humor, the unhappy experience of this panoramist who, having lost his musical accompanist, unknowingly hires a local drunk to play the piano during the panorama. At the most inappropriate moments, such as the scene of the happy return of the Prodigal Son, the pianist launches into drinking songs, such as "Oh, we'll all get blind drunk, when Johnny comes marching home." Humor aside, the depiction of an evening's entertainment Twain gives is a vivid and engaging one; religious subjects were increasingly common subject for panoramas later in the century, when, facing competition from newer forms of entertainment, they were more often shown in schools and churches than in large public halls.

Surviving moving panoramas

Few moving panoramas have survived to this day, and conservation issues frequently prevent them from being shown in their original format. The most notable rediscovered moving panorama in the United States of America is the Grand Moving Panorama of Pilgrim's Progress, which was discovered after having been forgotten in storage after nearly a century at the York Institute in Saco, Maine by Tom Hardiman. It was found to incorporate designs by many of the leading painters of its day, including Jasper Francis Cropsey, Frederic Edwin Church, and Henry Courtney Selous (Selous was the in-house painter for the original Barker panorama in London for many years). The Peabody-Essex Museum in Salem, Massachusetts has Thomas F. Davidson's moving panorama of a Whaling Voyage (1860), and the New Bedford Whaling Museum in New Bedford, Massachusetts owns Russell & Purrington's panorama of a Whaling Voyage Round the World, though it is currently (2007) no longer on display. A Mormon Panorama also survives at Brigham Young University's Art Museum.

References

- ↑ see Banvard's Folly: Thirteen Tales of People Who Didn't Change the World, by Paul S. Collins, ISBN 0312300336

- ↑ Russell A. Potter, Arctic Spectacles: The Frozen North in Visual Culture, 1818-1875 (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2007)

- ↑ Rufus C. Somerby, as "Dr. Judd," "The Old Panorama", The Billboard, December 5 1903, pp. 25,26.

- ↑ From Sketches New and Old, Project Gutenberg text, available at http://www.gutenberg.org/etext/3189