Mission San Francisco de Asís: Difference between revisions

imported>Robert A. Estremo m (add <br />) |

imported>Robert A. Estremo (→California Statehood (1850 – 1900): Presidential proclamation) |

||

| Line 111: | Line 111: | ||

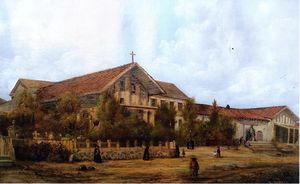

[[Image:Deakin SFO 1870 and Mission House.jpg|thumb|right|300px|{{Deakin SFO 1870 and Mission House.jpg/credit}}<br /> | [[Image:Deakin SFO 1870 and Mission House.jpg|thumb|right|300px|{{Deakin SFO 1870 and Mission House.jpg/credit}}<br /> | ||

Mission Dolores and the Mansion House, 1870.]] | Mission Dolores and the Mansion House, 1870.]] | ||

The [[California Gold Rush]] brought renewed activity to the Mission Dolores area. In the 1850s, two plank roads were constructed from what is today downtown San Francisco to the Mission, and the entire area became a popular resort and entertainment district.<ref>Johnson, p. 129</ref> Some of the Mission properties were sold or leased for use as saloons and gambling halls, racetracks were constructed, and fights between bulls and bears were staged for crowds. The Mission complex also underwent alterations. Part of the ''convento'' was converted to a two-story wooden wing for use as a seminary and priests' quarters, while another section became the "Mansion House," a popular tavern and way station for travelers.<ref>Johnson, p. 130</ref> President [[James Buchanan]] signed a proclamation on March 3, 1858 that restored ownership of the Mission proper to the Roman Catholic Church.<ref>Leffingwell, p. 152</ref> By 1876, the Mansion House portion of the ''convento'' had been razed and replaced with a large [[Gothic Revival]] brick church, designed to serve the growing population of immigrants who were now making the Mission area their home. During this period, wood clapboard siding was applied to the original adobe chapel walls as both a cosmetic and a protective measure; the veneer was later removed when the Mission was restored. | |||

The [[California Gold Rush]] brought renewed activity to the Mission Dolores area. In the 1850s, two plank roads were constructed from what is today downtown San Francisco to the Mission, and the entire area became a popular resort and entertainment district.<ref>Johnson, p. 129</ref> Some of the Mission properties were sold or leased for use as saloons and gambling halls, racetracks were constructed, and fights between bulls and bears were staged for crowds. The Mission complex also underwent alterations. Part of the ''convento'' was converted to a two-story wooden wing for use as a seminary and priests' quarters, while another section became the "Mansion House," a popular tavern and way station for travelers. <ref>Johnson, p. 130</ref> By 1876, the Mansion House portion of the ''convento'' had been razed and replaced with a large [[Gothic Revival]] brick church, designed to serve the growing population of immigrants who were now making the Mission area their home. During this period, wood clapboard siding was applied to the original adobe chapel walls as both a cosmetic and a protective measure; the veneer was later removed when the Mission was restored. | |||

===20th century and beyond (1901 – present)=== | ===20th century and beyond (1901 – present)=== | ||

Revision as of 17:51, 4 July 2013

| This article is part of a series on the Spanish missions in California  Mission San Francisco de Asís, circa 1899.[1] | |

| HISTORY | |

|---|---|

| Location: | San Francisco, California |

| Coordinates: | 37° 45′ 51.8″ N, 122° 25′ 37.3″ W |

| Name as Founded: | La Misión de Nuestro Padre San Francisco de Asís [2] |

| English Translation: | The Mission of Our Father, Saint Francis of Assisi |

| Patron Saint: | Saint Francis of Assisi, Italy [3] |

| Nickname(s): | "Mission Dolores" [4] |

| Founding Date: | June 29, 1776 [5] |

| Founded By: | Father Francisco Palóu; Father Junípero Serra [6] |

| Founding Order: | Sixth [3] |

| Military District: | Fourth [7] |

| Native Tribe(s): Spanish Name(s): |

Bay Miwok, Coast Miwok, Patwin Ohlone / Costeño |

| Primordial Place Name(s): | Chutchui [8] |

| SPIRITUAL RESULTS | |

| Baptisms: | 6,898 [9] |

| Marriages: | 2,043 [9] |

| Burials: | 5,166 [9] |

| Year of Neophyte Population Peak: | 1821 [10][11] |

| Neophyte Population: | 204 [10][11] |

| Neophyte Population in 1832: | 1,801 [10][11] |

| DISPOSITION | |

| Secularized: | 1834 [3] |

| Returned to the Church: | 1857 [3] |

| Caretaker: | Roman Catholic Archdiocese of San Francisco |

| Current Use: | Parish Church |

| National Historic Landmark: | #NPS-72000251 |

| Date added to the NRHP: | 1972 |

| California Historical Landmark: | #200 |

| Web Site: | http://www.missiondolores.org |

Mission San Francisco de Asís is a former religious outpost established by Spanish colonists on the west coast of North America in the present-day State of California. Founded on June 29, 1776 by Roman Catholics of the Franciscan Order, the settlement was the sixth in the twenty-one mission Alta California chain. Named after a 13th-century Italian Catholic friar and preacher (Francis of Assisi, the founder of the Franciscan Order), the site quickly gained the nickname "Mission Dolores" due to the presence of a nearby creek named Arroyo de Nuestra Señora de los Dolores (loosely, "Stream of Our Lady of Sorrows"). The oldest surviving structure in San Francisco, the Mission chapel is one of only two surviving buildings where Father Junípero Serra is known to have officiated. Designated as both a National Historic Landmark and a California Historical Landmark, in 1952 Pope Pius XII elevated Mission Dolores to the status of a Minor Basilica. Today the chapel serves as a parish church within the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of San Francisco.

History

Mission Period (1769 – 1833)

The original Mission consisted of a log and thatch structure dedicated on October 9, 1776 after the required church documents arrived. It was located about a block-and-a-half east of the present Mission, near what is today the intersection of Camp and Albion Streets, on the shores of a lake (long since filled) called Lago de los Dolores.[4] A historical marker is currently placed at that location. A member of the Anza Expedition of 1775-1776, Friar Pedro Font, wrote about the spot chosen for the Mission:

We rode about one league to the east [from the Presidio], one to the east-southeast, and one to the southeast, going over hills covered with bushes, and over valleys of good land. We thus came upon two lagoons and several springs of good water, meanwhile encountering much grass, fennel and other good herbs. When we arrived at a lovely creek, which because it was the Friday of Sorrows, we called the [creek] Arroyo de los Dolores ... On the banks of the Arroyo ... we discovered many fragrant chamomiles and other herbs, and many wild violets. Near the streamlet the lieutenant planted a little corn and some garbanzos in order to try out the soil, which to us appeared good.[12]

The present Mission church was dedicated in 1791. It was constructed of adobe and part of a complex of buildings used for housing, agricultural and manufacturing enterprises (see Architecture of the California Missions). Though most of the Mission complex, including the quadrangle and convento, has either been altered or demolished outright during the intervening years, the chapel façade has remained relatively unchanged since its construction in 1782–1791.

According to Mission historian Brother Guire Cleary, the early 19th century saw the greatest period of activity at San Francisco de Asís:

At its peak in 1810–1820, the average Indian population at Pueblo Dolores was about 1,100 persons. The California missions were not only houses of worship. They were farming communities, manufacturers of all sorts of products, hotels, ranches, hospitals, schools, and the centers of the largest communities in the state...in 1810 the Mission owned 11,000 sheep, 11,000 cows, and thousands of horses, goats, pigs, and mules. Its ranching and farming operations extended as far south as San Mateo and east to Alameda. Horses were corralled on Potrero Hill, and the milking sheds for the cows were located along Dolores Creek at what is today Mission High School. Twenty looms were kept in operation to process wool into cloth. The circumference of the mission's holdings were said to have been about 125 miles.[13]

In 1817, Mission San Rafael Arcángel was established as an asistencia to act as a hospital for the Mission, though it would later be granted full mission status in 1822. The Mexican War of Independence (1810–1821) strained relations between the Mexican government and the California missions. Supplies were scant, and the Indians who worked at the missions continued to suffer terrible losses from disease and cultural disruption (more than 5,000 Indians are thought to have been buried in the cemetery adjacent to the Mission).

Rancho Period (1834 – 1849)

In 1834, the Mexican government enacted secularization laws whereby most church property was sold or granted to private owners. In practical terms, this meant that the missions would hold title only to the churches, the residences of the priests and a small amount of land surrounding the church for use as gardens. In the period that followed, Mission Dolores fell on very hard times. By 1842, only eight Christian Indians were living at the Mission.[13]

California Statehood (1850 – 1900)

The California Gold Rush brought renewed activity to the Mission Dolores area. In the 1850s, two plank roads were constructed from what is today downtown San Francisco to the Mission, and the entire area became a popular resort and entertainment district.[14] Some of the Mission properties were sold or leased for use as saloons and gambling halls, racetracks were constructed, and fights between bulls and bears were staged for crowds. The Mission complex also underwent alterations. Part of the convento was converted to a two-story wooden wing for use as a seminary and priests' quarters, while another section became the "Mansion House," a popular tavern and way station for travelers.[15] President James Buchanan signed a proclamation on March 3, 1858 that restored ownership of the Mission proper to the Roman Catholic Church.[16] By 1876, the Mansion House portion of the convento had been razed and replaced with a large Gothic Revival brick church, designed to serve the growing population of immigrants who were now making the Mission area their home. During this period, wood clapboard siding was applied to the original adobe chapel walls as both a cosmetic and a protective measure; the veneer was later removed when the Mission was restored.

20th century and beyond (1901 – present)

During the 1906 San Francisco earthquake, the adjacent brick church was destroyed. By contrast, the original adobe Mission, though damaged, remained in relatively good condition. However, the ensuing fire touched off by the earthquake reached almost to the Mission's doorstep. To prevent the spread of flames, the Convent and School of Notre Dame across the street was dynamited by firefighters; nevertheless, nearly all the blocks east of Dolores Street and north of 20th street were consumed by flames. In 1913, construction began on a new church (now known as the Mission Dolores Basilica) adjacent to the Mission, which was completed in 1918. This structure was further remodeled in 1926 with churrigueresque ornamentation inspired by the Panama-California Exposition held in San Diego's Balboa Park. A sensitive restoration of the original adobe Mission was undertaken in 1917 by the noted architect, Willis Polk. In 1952, San Francisco Archbishop John J. Mitty, announced that Pope Pius XII had elevated Mission Dolores to the status of a Minor Basilica. This was the first designation of a basilica west of the Mississippi and the fifth basilica named in the United States. Today, the larger, newer church is called "Mission Dolores Basilica" while the original adobe structure retains the name of Mission Dolores.

The San Francisco de Asís cemetery, which adjoins the property on the south side, was originally much larger than its present boundaries, running west almost to Church Street and north into what is today 16th Street. It was reduced in various stages, starting with the extension of 16th Street through the former Mission grounds in 1889, and later by the construction of the Mission Dolores Basilica Center and the Chancery Building of the Archdiocese of San Francisco in the 1950s. Some remains were reburied on-site in a mass grave, while others were relocated to various Bay Area cemeteries. Today, most of the former cemetery grounds are covered by a paved playground behind the Mission Dolores School. The cemetery that currently remains underwent a careful restoration in the mid-1990s. The Mission is still an active church in San Francisco. The Mission District is the name of the adjacent neighborhood.

Legacy

Other designations

- California Historical Landmark #327-1 site of original Mission Dolores chapel and Dolores Lagoon

- California Historical Landmark #393 — "The Hospice," an outpost of Mission Dolores founded in 1800 in San Mateo, California

- California Historical Landmark #784 — El Camino Real (the northernmost point visited by Father Serra)

Miscellany

- In the Alfred Hitchcock filmVertigo, detective Scottie Ferguson (James Stewart) follows Madeleine Elster (Kim Novak) into Mission Dolores and out to the cemetery, where she lays flowers at the grave of "Carlotta Valdes." Although the grave marker was fictional and set up specifically for the film, it was reportedly left to stand in the cemetery for a number of years after filming.

- A dining car named Mission Dolores was part of the train The City of San Francisco, jointly operated by the Chicago and North Western Railway, the Southern Pacific Railroad, and the Union Pacific Railroad between Chicago and Oakland, California until 1971.

Notes and references

- ↑ (PD) Painting: Edwin Deakin

- ↑ Leffingwell, p. 149

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 Krell, p. 139

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Young, p. 117

- ↑ Yenne, p. 64

- ↑ Ruscin, p. 196

- ↑ Forbes, p. 202

- ↑ Ruscin, p. 195

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 Krell, p. 315: as of December 31, 1832; information adapted from Engelhardt's Missions and Missionaries of California.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 Krell, p. 315: Information adapted from Engelhardt's Missions and Missionaries of California.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 Engelhardt 1920, pp. 300-301.

- ↑ Englehardt, p. 38

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Cleary

- ↑ Johnson, p. 129

- ↑ Johnson, p. 130

- ↑ Leffingwell, p. 152

- ↑ (CC) Photo: Robert A. Estremo

- ↑ Krell, p. 148: The architectural style was influenced by designs exhibited at San Diego's Panama-California Exposition in 1915.