Relative permeability: Difference between revisions

imported>John R. Brews mNo edit summary |

imported>John R. Brews (sources) |

||

| Line 23: | Line 23: | ||

:<math>d^2\mathbf{F_{ij}} = I_i I_j \frac{\mu_r \mu_0} {4\pi} \frac{1}{r^2_{ij}}\left( \ (d \boldsymbol{\ell_i \cdot} d\boldsymbol{\ell_j})\mathbf{\hat{u}_{ij}}-( \mathbf{ \hat{u}_{ij}\cdot } d\boldsymbol{ \ell_i} )d\boldsymbol{\ell_j}\right ) \ , </math> | :<math>d^2\mathbf{F_{ij}} = I_i I_j \frac{\mu_r \mu_0} {4\pi} \frac{1}{r^2_{ij}}\left( \ (d \boldsymbol{\ell_i \cdot} d\boldsymbol{\ell_j})\mathbf{\hat{u}_{ij}}-( \mathbf{ \hat{u}_{ij}\cdot } d\boldsymbol{ \ell_i} )d\boldsymbol{\ell_j}\right ) \ , </math> | ||

which is not | which is obviously not symmetric under exchange of the indices ''i'' and ''j'', and violates Newton's law of action and reaction,<ref name=Moon> | ||

{{cite journal |author=P. Moon and DE Spencer |journal=J. Franklin Inst. |volume=vol 257 |pages=pp. 203, 305, 369 |year=1954 |title=The Coulomb force and the Ampère force & Interpretation of Ampère experiments & A new electrodynamics}} | |||

</ref> but is readily derived from the [[Biot-Savart law]], and is the expression for the force found in text books. | |||

Empirically it is observed that the force may increase or decreases due to the presence of the magnetic medium, hence the relative permittivity μ<sub>r</sub> may be greater than or less than 1. For simple media, if μ<sub>r</sub> < 1, the medium is termed ''diamagnetic''; if > 1 ''paramagnetic''. Only [[classical vacuum]] has μ<sub>r</sub> = 1 (exact). A typical diamagnetic susceptibility is about −10<sup>−5</sup>, while a typical paramagnetic susceptibility is about 10<sup>−4</sup>. It should be noted that the use of a constant as the relative permeability of a substance is an approximation, even for [[Vacuum (quantum electrodynamic)|quantum vacuum]]. A more complete representation recognizes that all media exhibit departures from this approximation, in particular, a dependence on field strength, a dependence upon the rate of variation of the field in both time and space, and a dependence upon the direction of the field. In many materials these dependencies are slight; in others, like [[Ferromagnetism|ferromagnets]], they are pronounced. | Empirically it is observed that the force may increase or decreases due to the presence of the magnetic medium, hence the relative permittivity μ<sub>r</sub> may be greater than or less than 1. For simple media, if μ<sub>r</sub> < 1, the medium is termed ''diamagnetic''; if > 1 ''paramagnetic''. Only [[classical vacuum]] has μ<sub>r</sub> = 1 (exact). A typical diamagnetic susceptibility is about −10<sup>−5</sup>, while a typical paramagnetic susceptibility is about 10<sup>−4</sup>. It should be noted that the use of a constant as the relative permeability of a substance is an approximation, even for [[Vacuum (quantum electrodynamic)|quantum vacuum]]. A more complete representation recognizes that all media exhibit departures from this approximation, in particular, a dependence on field strength, a dependence upon the rate of variation of the field in both time and space, and a dependence upon the direction of the field. In many materials these dependencies are slight; in others, like [[Ferromagnetism|ferromagnets]], they are pronounced. | ||

Revision as of 11:36, 18 April 2011

In physics, in particular in magnetostatics, the relative permeability is an intrinsic property of a magnetic material. It is usually denoted by μr. For simple magnetic materials, using SI units, μr is related to the proportionality constant between the magnetic flux density B and the magnetic field H, namely B = μr μ0 H, where μ0 is the magnetic constant. The relative permeability describes the ease by which a magnetic medium may be magnetized.

A related quantity is the magnetic susceptibility, denoted by χm, related to the magnetic permeability in SI units by:[1]

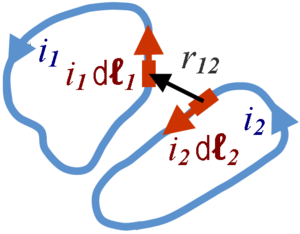

The Ampère force exerted between infinitesimal current elements from two loops carrying currents Ii and Ij and immersed in a magnetic medium with relative permeability μr is changed by a factor μr. The infinitesimal current elements have vector components Iidℓi and Ijdℓj where the incremental lengths are directed along the wire at the location of the element, and pointing in the direction of the current. Ampère's original force law is:[2]

with ûij a unit vector pointing along the line joining element j to element i and rij the length of this line. The force element is second order because it is a product of two infinitesimals. This force law leads to the same force between closed current loops as the more commonly used Grassmann's law:

which is obviously not symmetric under exchange of the indices i and j, and violates Newton's law of action and reaction,[3] but is readily derived from the Biot-Savart law, and is the expression for the force found in text books.

Empirically it is observed that the force may increase or decreases due to the presence of the magnetic medium, hence the relative permittivity μr may be greater than or less than 1. For simple media, if μr < 1, the medium is termed diamagnetic; if > 1 paramagnetic. Only classical vacuum has μr = 1 (exact). A typical diamagnetic susceptibility is about −10−5, while a typical paramagnetic susceptibility is about 10−4. It should be noted that the use of a constant as the relative permeability of a substance is an approximation, even for quantum vacuum. A more complete representation recognizes that all media exhibit departures from this approximation, in particular, a dependence on field strength, a dependence upon the rate of variation of the field in both time and space, and a dependence upon the direction of the field. In many materials these dependencies are slight; in others, like ferromagnets, they are pronounced.

Notes

- ↑ For example see Yehuda Benzion Band. Light and matter: electromagnetism, optics, spectroscopy and lasers. John Wiley and Sons, p. 242. ISBN 0471899313.

- ↑ See for example, André Koch Torres Assis (1994). Weber's electrodynamics. Springer, p. 86. ISBN 0792331370. , or Marcelo de Almeida Bueno, André Koch Torres Assis (2001). “§5.1: Ampère's force”, Inductance and force calculations in electrical circuits. Nova Science Publishers, pp. 51 ff. ISBN 9781560729174.

- ↑ P. Moon and DE Spencer (1954). "The Coulomb force and the Ampère force & Interpretation of Ampère experiments & A new electrodynamics". J. Franklin Inst. vol 257: pp. 203, 305, 369.