imported>Chunbum Park |

imported>John Stephenson |

| (174 intermediate revisions by 8 users not shown) |

| Line 1: |

Line 1: |

| == '''[[British and American English]]''' == | | {{:{{FeaturedArticleTitle}}}} |

| ''by [[User:Ro Thorpe|Ro Thorpe]] and others <small>([[User:Hayford Peirce|Hayford Peirce]], [[User:John Stephenson|John Stephenson]], [[User:Peter Jackson|Peter Jackson]], [[User:Chris Day|Chris Day]], [[User:Martin Baldwin-Edwards|Martin Baldwin-Edwards]], and [[User:J. Noel Chiappa|J. Noel Chiappa]])</small>''

| | <small> |

| ----

| | ==Footnotes== |

| Between '''[[British English]] and [[American English]]''' there are numerous differences in the areas of [[lexis|vocabulary]], [[spelling]], and [[phonology]]. This article compares the forms of British and American speech normally studied by foreigners: the former includes the [[Accent (linguistics)|accent]] known as [[Received Pronunciation]], or RP; the latter uses [[Midland American English]], which is normally perceived to be the least marked American [[dialect]]. Actual speech by educated British and American speakers is more varied, and that of uneducated speakers still more. [[Grammar|Grammatical]] and lexical differences between British and American English are, for the most part, common to all dialects, but there are many regional differences in pronunciation, vocabulary, usage and slang, some subtle, some glaring, some rendering a sentence incomprehensible to a speaker of another variant.

| | {{reflist|2}} |

| | | </small> |

| American and British English both diverged from a common ancestor, and the evolution of each language is tied to social and cultural factors in each land. Cultural factors can affect one's understanding and enjoyment of language; consider the effect that [[slang]] and [[double entendre]] have on humour. A joke is simply not funny if the [[pun]] upon which it is based can't be understood because the word, expression or cultural icon upon which it is based does not exist in one's variant of English. Or, a joke may be only partially understood, that is, understood on one level but not on another, as in this exchange from the [[Britcom]] ''[[Dad's Army]]'':

| |

| | |

| Fraser: Did ya hear the story of the old empty barn?

| |

| Mainwaring: Listen, everyone, Fraser's going to tell a story.

| |

| Fraser: The story of the old empty barn: well, there was nothing in it!

| |

| | |

| Americans would 'get' part of the joke, which is that a barn that is empty literally has nothing in it. However, in Commonwealth English, 'there's nothing in it' also means something that is trivial, useless or of no significance.

| |

| | |

| But it is not only humour that is affected. Items of cultural relevance change the way English is expressed locally. A person can say "I was late, so I ''Akii-Bua'd'' (from [[John Akii-Bua]], Ugandan hurdler) and be understood all over East Africa, but receive blank stares in [[Australia]]. Even if the meaning is guessed from context, the nuance is not grasped; there is no resonance of understanding. Then again, because of evolutionary divergence; people can believe that they are speaking of the same thing, or that they understand what has been said, and yet be mistaken. Take adjectives such as 'mean' and 'cheap'. Commonwealth speakers still use 'mean' to mean 'parsemonious', Americans understand this usuage, but their first use of the word 'mean' is 'unkind'. Americans use 'cheap' to mean 'stingy', but while Commonwealth speakers understand this, there is a danger that when used of a person, it can be interpreted as 'disreputable' 'immoral' (my grandmother was so ''cheap''). The verb 'to table' a matter, as in a conference, is generally taken to mean 'to defer', in American English, but as 'to place on the table', i.e. to bring up for discussion, in Commonwealth English.

| |

| | |

| English is a flexible and quickly-evolving language; it simply absorbs and includes words and expressions for which there is no current English equivalent; these become part of the regional English. American English has hundreds of loan words acquired from its [[immigration|immigrants]]: these can eventually find their way into widespread use, (''[[spaghetti]]'', ''mañana''), or they can be restricted to the areas in which immigrant populations live. So there can be variances between the English spoken in [[New York City]], [[Chicago]], and [[San Francisco]]. Thanks to Asian immigration, a working-class [[London|Londoner]] asks for a ''cuppa cha'' and receives the tea he requested. This would probably be understood in [[Kampala]] and [[New Delhi]] as well, but not necessarily in [[Boise]], [[Idaho]].

| |

| | |

| Cultural exchange also has an impact on language. For example, it is possible to see a certain amount of Americanization in the British English of the last 50 years. This influence is not entirely one-directional, though, as, for instance, the previously British English 'flat' for 'apartment' has gained in usage among American twenty-somethings. Similarly the American pronunciation of '[[aunt]]' has changed during the last two decades, and it is considered classier to pronounce 'aunt' in the [[Commonwealth]] manner, even for speakers who continue to rhyme 'can't' and 'shan't' with 'ant'. [[Australian English]] is based on the language of the Commonwealth, but has also blended indigenous, immigrant and American imports.

| |

| | |

| Applying these same phenomena to the rest of the English-speaking world, it becomes clear that though the "official" differences between Commonwealth and American English can be more or less delineated, the English language can still vary greatly from place to place.

| |

| | |

| ''[[British and American English|.... (read more)]]''

| |

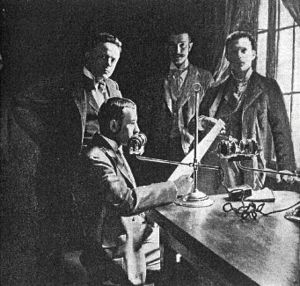

1901 photograph of a stentor (announcer) at the Budapest

Telefon Hirmondó.

Telephone newspaper is a general term for the telephone-based news and entertainment services which were introduced beginning in the 1890s, and primarily located in large European cities. These systems were the first example of electronic broadcasting, and offered a wide variety of programming, however, only a relative few were ever established. Although these systems predated the invention of radio, they were supplanted by radio broadcasting stations beginning in the 1920s, primarily because radio signals were able to cover much wider areas with higher quality audio.

History

After the electric telephone was introduced in the mid-1870s, it was mainly used for personal communication. But the idea of distributing entertainment and news appeared soon thereafter, and many early demonstrations included the transmission of musical concerts. In one particularly advanced example, Clément Ader, at the 1881 Paris Electrical Exhibition, prepared a listening room where participants could hear, in stereo, performances from the Paris Grand Opera. Also, in 1888, Edward Bellamy's influential novel Looking Backward: 2000-1887 foresaw the establishment of entertainment transmitted by telephone lines to individual homes.

The scattered demonstrations were eventually followed by the establishment of more organized services, which were generally called Telephone Newspapers, although all of these systems also included entertainment programming. However, the technical capabilities of the time meant that there were limited means for amplifying and transmitting telephone signals over long distances, so listeners had to wear headphones to receive the programs, and service areas were generally limited to a single city. While some of the systems, including the Telefon Hirmondó, built their own one-way transmission lines, others, including the Electrophone, used standard commercial telephone lines, which allowed subscribers to talk to operators in order to select programming. The Telephone Newspapers drew upon a mixture of outside sources for their programs, including local live theaters and church services, whose programs were picked up by special telephone lines, and then retransmitted to the subscribers. Other programs were transmitted directly from the system's own studios. In later years, retransmitted radio programs were added.

During this era telephones were expensive luxury items, so the subscribers tended to be the wealthy elite of society. Financing was normally done by charging fees, including monthly subscriptions for home users, and, in locations such as hotel lobbies, through the use of coin-operated receivers, which provided short periods of listening for a set payment. Some systems also accepted paid advertising.