Great Depression/Tutorials: Difference between revisions

imported>Nick Gardner |

imported>Nick Gardner |

||

| Line 81: | Line 81: | ||

:''(the following paragraph has been summarised from Ben Bernanke's speech to the Conference to Honor Milton Friedman, University of Chicago, Chicago, Illinois November 8, 2002 - Friedman's ninetieth birthday - November 8, 2002 [http://www.federalreserve.gov/BOARDDOCS/SPEECHES/2002/20021108/default.htm])'' | :''(the following paragraph has been summarised from Ben Bernanke's speech to the Conference to Honor Milton Friedman, University of Chicago, Chicago, Illinois November 8, 2002 - Friedman's ninetieth birthday - November 8, 2002 [http://www.federalreserve.gov/BOARDDOCS/SPEECHES/2002/20021108/default.htm])'' | ||

In the spring of 1928 there was a significant tightening of monetary policy by the Federal Reserve Board that continued until the stock market crash of October 1929. The Board's reason for that action was not concern about inflation - which hardly existed at the time - but concern about speculation on Wall Street, prompted by the rising stock market and the associated increases in bank loans to brokers. As Friedman and Schwartz noted (p. 289), "by July, the discount rate had been raised in New York to 5 per cent, the highest since 1921, and the System's holdings of government securities had been reduced to a level of over $600 million at the end of 1927 to $210 million by August 1928, despite an outflow of gold." Strong reservations about that policy had | In the spring of 1928 there was a significant tightening of monetary policy by the Federal Reserve Board that continued until the stock market crash of October 1929. The Board's reason for that action was not concern about inflation - which hardly existed at the time - but concern about speculation on Wall Street, prompted by the rising stock market and the associated increases in bank loans to brokers. As Friedman and Schwartz noted <ref> Milton Friedman and Anna Schwartz ''A Monetary History of the United States 1867-1960'' (p. 289), Princeton University Press for NBER, 1963</ref>., "by July, the discount rate had been raised in New York to 5 per cent, the highest since 1921, and the System's holdings of government securities had been reduced to a level of over $600 million at the end of 1927 to $210 million by August 1928, despite an outflow of gold." Strong reservations about that policy had been expressed by one of the Board's members, Benjamin Strong, the influential Governor of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, but Strong died in October and the policy was supported by his successor, George Harrison, and the discount rate was raised a further point to 6 per cent in the following year. That move was followed by a period of falling prices and weaker economic activity. According to Friedman and Schwartz "During the two months from the cyclical peak in August 1929 to the crash, production, wholesale prices, and personal income fell at annual rates of 20 per cent, 7-1/2 per cent, and 5 per cent, respectively." and after the stock market crash, economic decline became even more precipitous. (James Hamilton <ref> James Hamilton: ''Monetary Factors in the Great Depression'', Journal of Monetary Economics, 1987 </ref> has shown that the Board's desire to slow outflows of . gold to France had then resulted in massive flows of gold from abroad and a further tightening of monetary policy.) | ||

That move was followed by a period of falling prices and weaker economic activity. According to Friedman and Schwartz "During the two months from the cyclical peak in August 1929 to the crash, production, wholesale prices, and personal income fell at annual rates of 20 per cent, 7-1/2 per cent, and 5 per cent, respectively." and after the stock market crash, economic decline became even more precipitous. (James Hamilton <ref> James Hamilton: ''Monetary Factors in the Great Depression'', Journal of Monetary Economics, 1987 </ref> has shown that the Board's desire to slow outflows of . gold to France had then resulted in massive flows of gold from abroad and a further tightening of monetary policy.) | |||

====The stock market boom and crash==== | ====The stock market boom and crash==== | ||

Revision as of 09:57, 16 January 2009

For definitions of the terms shown in italics see the glossary on the Related Articles subpage [4].

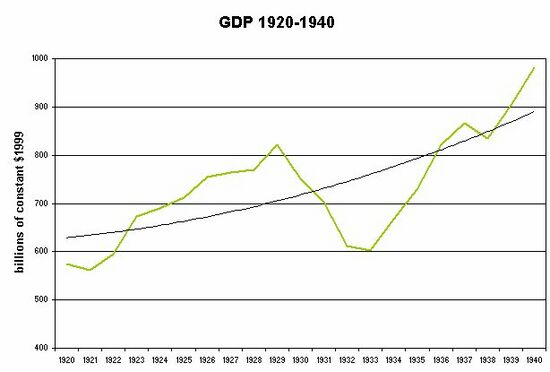

Statistics of the US economy

Depression Data[1] 1929 1931 1933 1937 1938 1940 Real Gross National Product (GNP) 1 101.4 84.3 68.3 103.9 103.7 113.0 Consumer Price Index 2 122.5 108.7 92.4 102.7 99.4 100.2 Index of Industrial Production 2 109 75 69 112 89 126 Money Supply M2 ($ billions) 46.6 42.7 32.2 45.7 49.3 55.2 Exports ($ billions) 5.24 2.42 1.67 3.35 3.18 4.02 Unemployment (% of civilian work force) 3.1 16.1 25.2 13.8 16.5 13.9

1 in 1929 dollars

2 1935-39 = 100

Causes and remedies

Economics then and now

Contributory factors

Monetary policy

- (the following paragraph has been summarised from Ben Bernanke's speech to the Conference to Honor Milton Friedman, University of Chicago, Chicago, Illinois November 8, 2002 - Friedman's ninetieth birthday - November 8, 2002 [5])

In the spring of 1928 there was a significant tightening of monetary policy by the Federal Reserve Board that continued until the stock market crash of October 1929. The Board's reason for that action was not concern about inflation - which hardly existed at the time - but concern about speculation on Wall Street, prompted by the rising stock market and the associated increases in bank loans to brokers. As Friedman and Schwartz noted [1]., "by July, the discount rate had been raised in New York to 5 per cent, the highest since 1921, and the System's holdings of government securities had been reduced to a level of over $600 million at the end of 1927 to $210 million by August 1928, despite an outflow of gold." Strong reservations about that policy had been expressed by one of the Board's members, Benjamin Strong, the influential Governor of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, but Strong died in October and the policy was supported by his successor, George Harrison, and the discount rate was raised a further point to 6 per cent in the following year. That move was followed by a period of falling prices and weaker economic activity. According to Friedman and Schwartz "During the two months from the cyclical peak in August 1929 to the crash, production, wholesale prices, and personal income fell at annual rates of 20 per cent, 7-1/2 per cent, and 5 per cent, respectively." and after the stock market crash, economic decline became even more precipitous. (James Hamilton [2] has shown that the Board's desire to slow outflows of . gold to France had then resulted in massive flows of gold from abroad and a further tightening of monetary policy.)

The stock market boom and crash

The Gold Standard

The gold standard theory of the depression has been summarised by Bernanke and Carey [4], broadly as follows.

- In order to curb the New York stock market boom, the Federal Reserve Bank imposed a contraction of the money supply in the late 1920s and several other major countries followed suit. That contraction was transmitted to other industrialised countries as a result of the operation of the gold standard. A rush for the safety of gold prompted by the 1931 banking crisis, the sterilisation of gold inflows by countries with balance of payments surpluses, the substitution of gold for foreign exchange reserves, and runs on many banks, all led to increases in the gold reserves required to back the issue of money and consequently to sharp and unintended reductions in the international money supply. The resulting deflation was avoidable only by a countervailing money creation by central banks but, in the absence of international agreement to do so, countries could take that action only by abandonong the gold standard.

- I believe some of the crash was inevitable because of over-indebtedness, but the depression was not inevitable. The reason is that the deflation which went with the over-indebtedness was not necessary. We can always control the price level. [5] Irving Fisher

Trade Decline and the U.S. Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act

Many economists at the time argued that the sharp decline in international trade after 1930 helped to worsen the depression, especially for countries dependent on foreign trade. Most historians and economists assign the American Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act of 1930 part of the blame for worsening the depression by reducing international trade and causing retaliation. Foreign trade was a small part of overall economic activity in the United States; it was a much larger factor in most other countries.[6] The average rate of duties on dutiable imports for 1921-1925 was 26% but under the new tariff it jumped to 50% in 1931-1935.

In dollar terms, American exports declined from about $5.2 billion in 1929 to $1.7 billion in 1933; but prices also fell, so the physical volume of exports only fell in half. Hardest hit were farm commodities such as wheat, cotton, tobacco, and lumber. Many American farms had been heavily mortgaged as farmers bought overpriced land in the bubble of 1919-20, and defaulted.

Rival explanations

Irving Fisher

An influential economist in the early 20th century, Irving Fisher is now best known for his forecast that there would be no stock market crash - that he made immediately before it happened [7], (although in his defence he has pointed out that only he had predicted the inevitability of a depression, although he had seriously underestimated its severity [8]). Fisher's explanation of the depression was that an economy with a high level of debt had suffered a shock that had led to a loss of confidence which had prompted the widespread liquidation of debts by "distress selling", causing a sharp fall in share prices and a contraction in bank deposits; and that this had triggered a deflation which increased the stock of debt in real terms. What had followed had been a perverse cycle of further price reductions which led to further pressure to liquidate debts, which led to further price falls, and so on, which he called "debt deflation" [9]. . Fisher maintained throughout the 1930s that a financial crash need not affect the real economy provided that there was a sufficient expansion of the money supply [10]. The shock to which Fisher attributed the onset of the depression was the sudden reversal of the Federal Reserve Bank's monetary policy that is discussed below. .

Lionel Robbins

Lionel Robbins of the London School of Economics was at the time an influential proponent of the theories of the Austrian School of economics (although he subsequently adopted Keynesianism). His protegé, Friederich Hayek, had developed a theory of recessions[11], which he used in 1934 to explain the then current depression [12].

Milton Friedman

Ben Bernanke

Barry Eichgengreen

Peter Temin

Rival remedies

Deficit Spending

The British economist John Maynard Keynes argued that the low aggregate demand in the economy caused a multiple decline in income, keeping the economy in an equilibrium well below full employment. In this situation, the economy may reach perfect balance, but at a cost of a high unemployment. Keynesian economists were increasingly calling for government to take up the slack by increasing government spending. Although Keynes's specific policy prescriptions at the time were vague (Perelman 1989) [19], his basic approach was to let business be free to do as it would choose, while creating a macroeconomic climate in which investment would be brisk or, using Keyne's own words - which became famous - creating a macroeconomic environment capable of awakening the "animal spirits" of entrepreneurs. Animal spitirts are a particular sort of confidence, "naive optimism"; "the thought of ultimate loss which often overtakes pioneers, as experience undoubtedly tells us and them, is put aside as a healthy man puts aside the expectation of death".John Maynard Keynes

References

- ↑ Milton Friedman and Anna Schwartz A Monetary History of the United States 1867-1960 (p. 289), Princeton University Press for NBER, 1963

- ↑ James Hamilton: Monetary Factors in the Great Depression, Journal of Monetary Economics, 1987

- ↑ Ben Bernanke Asset-Price "Bubbles" and Monetary Policy, Speech to the New York Chapter of the National Association for Business Economics, October 15, 2002

- ↑ Ben Bernanke and Kevin Carey: "Nominal Wage Stickiness and Aggregate Supply in the Great Depression", in Ben Bernanke: Essays on The Great Depression, page276, Princeton University Press 2000

- ↑ Irving Fisher. Discussion by Professor Irving Fisher (On the causes of the Great Depression)

- ↑ see [3]

- ↑ Irving Fisher is widely reported to have said " stock prices have reached what looks like a permanently high plateau" in September 1929

- ↑ Discussion by Professor Irving Fisher

- ↑ Irving Fisher : The Debt-Deflation Theory of Great Depressions, Econometrica 1933

- ↑ Giovanni Pavanelli: The Great Depression in Irving Fisher's Thought December 2001

- ↑ Friedrich Hayek: Monetary Theory and the Trade Cycle, 1933 (reprinted by von Mises Institute 2008)

- ↑ : Harold Robbins The Great Depression 1934

- ↑ Lionel Robbins: The Great Depression, Macmillan, 1934

- ↑ Lionel Robbins: Autobiography of an Economist, Macmillan, 1971

- ↑ Murray Rothbart: America's Great Depression, von Mises Institute, 1963

- ↑ Friedman and Schwartz, A Monetary History of the United States, (1963)

- ↑ Ben Bernanke The Great Depression Princeton University Press, 2000

- ↑ Petter Temin: Lessons from the Great Depression The Lionel Robbins Lectures for 1989 MIT Press 1989

- ↑ PERELMAN, Michael. Keynes, Investment Theory and the Economic Slowdown: The Role of Replacement Investment and q-Ratios. NY and London: St. Martin's and Macmillan, 1989. ISBN 0333464966