Treaty of Guadalupe-Hidalgo: Difference between revisions

imported>Shamira Gelbman m (syntax) |

imported>Shamira Gelbman (1857 --> 1847) |

||

| (One intermediate revision by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{subpages}} | {{subpages}} | ||

The '''Treaty of Guadalupe-Hidalgo''' was the 1848 treaty that ended the [[Mexican-American War]] and created a boundary that added New Mexico, Arizona and California to the United States. After U.S. General [[Winfield Scott]] had captured Vera Cruz in 1847, President [[James K. Polk]] ordered a peace commissioner, [[Nicholas P. Trist]], to accompany Scott's army in its march toward Mexico City. Trist was the senior officer of the Department of State under Secretary of State [[James Buchanan]]. On October 1, | The '''Treaty of Guadalupe-Hidalgo''' was the 1848 treaty that ended the [[Mexican-American War]] and created a boundary that added New Mexico, Arizona and California to the United States. After U.S. General [[Winfield Scott]] had captured Vera Cruz in 1847, President [[James K. Polk]] ordered a peace commissioner, [[Nicholas P. Trist]], to accompany Scott's army in its march toward Mexico City. Trist was the senior officer of the Department of State under Secretary of State [[James Buchanan]]. On October 1, 1847, Polk ordered Trist's recall, in order to discourage false Mexican views of American anxiety for peace. Trist, however, delayed his departure and decided to remain and to assume the responsibility of negotiating a treaty substantially on the basis of the territorial demands of his original instructions from Buchanan. On Jan. 24, 1848, he was able to secure the completed draft of the treaty, which he and the Mexicans signed on Feb. 2, at Guadalupe-Hidalgo, a town near Mexico City. Polk submitted this treaty to the United States Senate. Much of the Senate debate centered on Article IX, which appeared to give special legal status to Catholics. The treaty's final version lacked all mention of Roman Catholicism, corporate Catholic property, and the Mexican hierarchy. The Senate ratified the revised version by a vote of 38 to 14 on May 30, 1848, ending the war | ||

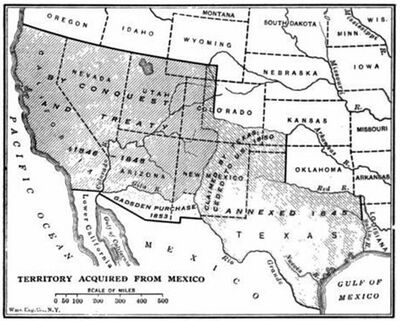

[[Image:1848gain.jpg|thumb|400px|territorial changes 1848]] | [[Image:1848gain.jpg|thumb|400px|territorial changes 1848]] | ||

| Line 12: | Line 12: | ||

<blockquote>The devastation at mid-century virtually wiped the slate clean. The state's mines were filled with water and caved in; its pasture land was empty. Those haciendas not abandoned by their owners were fortified with thick walls. The once-flourishing commerce of the northern trade routes was ruined. State govrnment barely functioned. Factionalism tore apart its politics. Chihuahuans lived under siege in constant fear."</blockquote> | <blockquote>The devastation at mid-century virtually wiped the slate clean. The state's mines were filled with water and caved in; its pasture land was empty. Those haciendas not abandoned by their owners were fortified with thick walls. The once-flourishing commerce of the northern trade routes was ruined. State govrnment barely functioned. Factionalism tore apart its politics. Chihuahuans lived under siege in constant fear."</blockquote> | ||

== | ==References== | ||

<references/> | <references/> | ||

Revision as of 09:51, 5 August 2009

The Treaty of Guadalupe-Hidalgo was the 1848 treaty that ended the Mexican-American War and created a boundary that added New Mexico, Arizona and California to the United States. After U.S. General Winfield Scott had captured Vera Cruz in 1847, President James K. Polk ordered a peace commissioner, Nicholas P. Trist, to accompany Scott's army in its march toward Mexico City. Trist was the senior officer of the Department of State under Secretary of State James Buchanan. On October 1, 1847, Polk ordered Trist's recall, in order to discourage false Mexican views of American anxiety for peace. Trist, however, delayed his departure and decided to remain and to assume the responsibility of negotiating a treaty substantially on the basis of the territorial demands of his original instructions from Buchanan. On Jan. 24, 1848, he was able to secure the completed draft of the treaty, which he and the Mexicans signed on Feb. 2, at Guadalupe-Hidalgo, a town near Mexico City. Polk submitted this treaty to the United States Senate. Much of the Senate debate centered on Article IX, which appeared to give special legal status to Catholics. The treaty's final version lacked all mention of Roman Catholicism, corporate Catholic property, and the Mexican hierarchy. The Senate ratified the revised version by a vote of 38 to 14 on May 30, 1848, ending the war

Important provisions of the treaty were 1) the Rio Grande River became the boundary line between Texas and Mexico (as Texas had claimed); 2) the boundary then was extended to just south of San Diego, giving California, Arizona and New Mexico to the U.S.; 3) in consideration of its boundary extensions, the United States government paid Mexico $3,000,000 at once and $12,000,000 with 6 percent interest on later dates; 4) the United States agreed to satisfy unpaid claims by Americans against the Mexican government and would exonerate Mexico from all claims made by American citizens prior to the date of the treaty. The United States assuming responsibility for the payment of the undecided claims to the extent of $3,250,000; and 5) the property rights enjoyed by the Hispanic population under Mexican rule would be respected by the United States, and the inhabitants would have one year to return to Mexico or stay and become full-fledged Amerian citizens.

Texas previously had claimed parts of the vast area the United States acquired by this treaty, but Mexico now for the first time surrendered them formally. Including these, the new acquisitions comprised all the territory later to be admitted to the Union as the states of Nevada, California, New Mexico, and Utah, and parts of Oklahoma, Kansas, Colorado, and Wyoming.

Areas that remained in Mexico saw very hard times after 1848, as the Indian raids intensified, draught ruined farming and cholera epidemics raged; mines were abandoned, and many villagers fled. Wasserman's description of Chihuahua applies as well to other states in northern Mexico:[1]

The devastation at mid-century virtually wiped the slate clean. The state's mines were filled with water and caved in; its pasture land was empty. Those haciendas not abandoned by their owners were fortified with thick walls. The once-flourishing commerce of the northern trade routes was ruined. State govrnment barely functioned. Factionalism tore apart its politics. Chihuahuans lived under siege in constant fear."

References

- ↑ Mark Wasserman, "Capitalists, Caciques, and Revolution: The Native Elite and Foreign Enterprise in Chihuahua, Mexico, 1854-1911. 1984. Page 25.