Joe Louis: Difference between revisions

imported>Todd Coles m (→Early Life) |

imported>Todd Coles m (→Amateur) |

||

| Line 22: | Line 22: | ||

==Boxing Career== | ==Boxing Career== | ||

====Amateur==== | ====Amateur==== | ||

Louis began to draw the attention of Brewster's owner [[Atler Ellis]], who with the help of [[Holman Williams]], began | Louis began to draw the attention of Brewster's owner [[Atler Ellis]], who with the help of [[Holman Williams]], began his formal training. His first amateur fight took place at the Naval Armory in Detroit, and was against a member of the 1932 [[Olympic]] boxing team, [[Johnny Miler]]. He was defeated in three rounds after being knocked down seven times. Louis was disheartened by his performance and temporarily gave up his training to work a regular job at the Ford factory. He would not stay away for long and quit his job in January of 1933 and returned to the gym. He reasoned that "if I'm going to hurt that much for twenty-five dollars a week, I might as well go back and try fighting again."<ref>Louis, p. 27 - At the time, amateur boxing could earn a boxer 25 dollars for a win and 7 dollars for a loss.</ref> | ||

Louis' second amateur fight was against [[Otis Thomas]] at the Forest Athletic Club. He knocked Thomas out in the first round. Louis would go on to defeat the next thirteen opponents he faced. His success led him to enter into the [[Golden Gloves]] and [[Amateur Athletic Union]] (AAU) tournaments. Louis would end up winning 50 of his 54 amateur fights, with 43 [[knockout]]s. | |||

====Professional==== | ====Professional==== | ||

In 1934, Louis moved to [[Chicago]], [[Illinois]], where he would be trained by [[Julian Black]] and [[John Roxborough]] for his professional career. His first professional fight was on July 4, 1934 at the Bacon Casino against Jack Kracken. He knocked Kracken out with a left hook in under 2 minutes. By the end of August, he was 5-0 with 4 knockouts. He would continue his dominance over the next 22 fights, until his first meeting with German Max Schmeling on June 19, 1936. | In 1934, Louis moved to [[Chicago]], [[Illinois]], where he would be trained by [[Julian Black]] and [[John Roxborough]] for his professional career. His first professional fight was on July 4, 1934 at the Bacon Casino against Jack Kracken. He knocked Kracken out with a left hook in under 2 minutes. By the end of August, he was 5-0 with 4 knockouts. He would continue his dominance over the next 22 fights, until his first meeting with German Max Schmeling on June 19, 1936. | ||

Revision as of 12:53, 2 August 2007

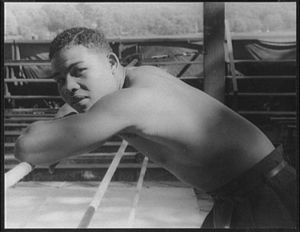

Joseph Louis Barrow (May 13, 1914 – April 13, 1981), known as Joe Louis and nicknamed "The Brown Bomber," was a highly successful professional boxer. During his career he defended his heavyweight championship 25 consecutive times over a period of 12 years, both of which are records. He is regarded by some people as the greatest heavyweight boxer off all-time.[1] He was also seen as both a black hero and a national hero in the United States, largely due to his defeat of the Nazi sponsored Max Schmeling.

Following Louis' death, President Ronald Reagan said, "Joe Louis was more than a sports legend -- his career was an indictment of racial bigotry and a source of pride and inspiration to millions of white and black people around the world."[2]

Early Life

Joe Louis was born in Lafayette, Alabama into a poor, sharecropping family with 8 children. When Joe was 2 his father, the son of a former slave, was admitted to the Searcy Hospital for the Negro Insane. After being told her husband had died, Louis' mother was remarried to another sharecropper named Patrick Brooks, who was a widower and also had 8 children.

In 1926, the family moved to Detroit, Michigan, where his father and brothers worked on the assembly line at a Ford plant. With the arrival of the Great Depression in the 1930's, his father and brothers lost their jobs and the family fell on hard times. Louis started attending the Bronson Vocational School, where he was learning to make furniture.

Eventually, things began to settle down at home and at his mother's insistence, Louis began taking violin lessons. The violin made him the object of ridicule for his vocational school classmates, except for Thurston McKinney who was a successful amateur boxer. McKinney invited Louis to come with him to Brewster's East Side Gymnasium. Eventually, McKinney invited Louis to spar with him. After being beaten around for a few rounds, Louis lost his temper and landed a right to McKinney's chin, nearly knocking him out. Thurston grinned and said, "Man, throw that violin away."[3] From that point forward, Louis dedicated his life to becoming a boxer.

Boxing Career

Amateur

Louis began to draw the attention of Brewster's owner Atler Ellis, who with the help of Holman Williams, began his formal training. His first amateur fight took place at the Naval Armory in Detroit, and was against a member of the 1932 Olympic boxing team, Johnny Miler. He was defeated in three rounds after being knocked down seven times. Louis was disheartened by his performance and temporarily gave up his training to work a regular job at the Ford factory. He would not stay away for long and quit his job in January of 1933 and returned to the gym. He reasoned that "if I'm going to hurt that much for twenty-five dollars a week, I might as well go back and try fighting again."[4]

Louis' second amateur fight was against Otis Thomas at the Forest Athletic Club. He knocked Thomas out in the first round. Louis would go on to defeat the next thirteen opponents he faced. His success led him to enter into the Golden Gloves and Amateur Athletic Union (AAU) tournaments. Louis would end up winning 50 of his 54 amateur fights, with 43 knockouts.

Professional

In 1934, Louis moved to Chicago, Illinois, where he would be trained by Julian Black and John Roxborough for his professional career. His first professional fight was on July 4, 1934 at the Bacon Casino against Jack Kracken. He knocked Kracken out with a left hook in under 2 minutes. By the end of August, he was 5-0 with 4 knockouts. He would continue his dominance over the next 22 fights, until his first meeting with German Max Schmeling on June 19, 1936.

Louis, being several years younger than Schmeling, was supposed to win the fight easily. But the former World Heavyweight Champion had been studying film of Louis' fights and found a weakness that he was able to take advantage of. Schmeling knocked Louis out in the twelfth round. Technically, this made Schmeling the number one contender to fight James Braddock for the championship, but some behind the scenes maneuvering by Louis' promoter Mike Jacobs gave Louis the title shot instead, which infuriated Schmeling. Louis went on to defeat Braddock by knockout to become the World Heavyweight Champion, a title he would hold for the next 12 years.

The stage was set for a rematch with Schmeling and this time the fight would seem all the more important. Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party were causing concern in the rest of the world, as they steered Germany away from democracy and promoted racial hatred. Schmeling, although not being a Nazi, had become a favorite of Hitler. There was much propaganda spread about this rematch from both America and Germany and was to be viewed as a great battle of the races. This national pressure, on top of the fact that Louis craved revenge for his previous loss, was a strong motivator and led him to say to a friend before the fight, "I'm scared I might kill Schmeling tonight."[5] The fight was incredibly short, with Louis administering Schmeling a severe beating and knocking him out in just over 2 minutes, propelling him to the status of national hero.

Louis go on to actively defend his title, which differed from the common practice of champions becoming notoriously inactive. He fought 21 title fights between 1937 and 1942, winning all but 3 by knockout. His opponents during this time frame earned the nickname of "The Bum of the Month Club".

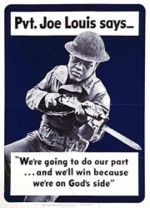

Military

After the bombing of Pearl Harbor, Louis was scheduled to fight Buddy Bear at Madison Square Garden. In an unprecedented gesture, Louis decided to donate his winnings from the fight to the Naval Relief Society, a charity that supported families of sailors killed in action. On January 10, 1942, the night after the fight, Louis volunteered for service in the United States Army.

At the time, the Army was still segregated and Louis was assigned to all black units. During his time at Fort Riley, Kansas, Louis became friends with Jackie Robinson, the man that would go on to break the color barrier in Major League Baseball. Robinson was an admirer of Louis, and found him not afraid to use his celebrity status to create opportunities for black troops. Louis used his connections in Washington to get Robinson and other blacks into officer candidate school.

Eventually, Louis was promoted to sergeant and the Army decided his value was not in fighting, but for providing a morale boost for the troops. He spent the rest of his time traveling across Europe and Africa putting on exhibition fights. Louis would retire from the military a month after the end of World War II.

End of career

Louis continued his title defenses, improving his streak to 25 title defenses. On September 27, he would lose to Ezzard Charles and lose the title. He would go on to fight several more times, retiring after an October 26, 1951 fight against Rocky Marciano in which he was knocked out. Louis finished his career with a record of 68-3.

Later life

Louis had managed to accumulate a large amount of debt during his career. From the beginning of his career in 1931 until the time he won the title in 1937, income tax rates had raised from 24 to 79 percent, and would eventually reach as high as 90 percent.[6]The high tax rate, coupled with Louis' generous spending habits - repaying his families debts, donations to military charities - led him to owe over 1 million dollars in back taxes to the Internal Revenue Service after World War II. Many of his final bouts were fought in order to try and pay the government back. He would also turn to a short lived career as a [professional wrestler]], several game show appearances, and finally working as a greeter at Caeser's Palace in Las Vegas.

Louis developed a drug problem and in 1969 collapsed in Manhattan. The collapse was due to cocaine usage. A year later he was readmitted to a hospital because he was suffering paranoid delusions. His health would continue to deteriorate, and he suffered a series of several strokes and heart problems, leaving him confined to a wheelchair. He died of a heart attack on April 13, 1981 in Las Vegas, shortly after attending a fight between Larry Holmes and Trevor Berbick. At the request of President Ronald Reagan, he was buried at Arlington National Cemetery.

Filmography

Movies

- Max Schmeling siegt über Joe Louis (1936)

- Spirit of Youth (1938) - Joe Thomas

- This Is The Army (1943) - Sgt. Joe Louis

- Joe Palooka, Champ (1946) - Himself

- Johnny at the Fair (1947) - Himself

- The Fight Never Ends (1949) - Himself

- The Square Jungle (1955) - Himself

- The Phynx (1970) - Himself

- The Super Fight (1970) - Himself (voice)

TV Show Appearances

- The Colgate Comedy Hour (1951) - Himself

- That Reminds Me (1952) - Himself

- Person to Person (1953) - Himself

- It Takes A Theif (1968) - Boxer

- V.I.P-Schaukel (1972) - Himself

- The Way It Was (3 episodes, 1975-77) - Himself

- Quincy M.E. (1977) - Himself

- ESPN Sportscentury (2000) - Himself

Documentaries

- Max Schmeling siegt über Joe Louis (1936)

- Roar of the Crowd (1953)

- Kings of the Ring: Four Legends of Heavyweight Boxing (2000)

References

Notes

- ↑ International Boxing Research Organization All Time Rankings. Retrieved on 2007-08-01.

- ↑ Statement By President Ronald Reagan on the Death of Former World Heavyweight Boxing Champion Joe Louis April 13, 1981. Retrieved on 2007-08-01.

- ↑ Louis, p. 20

- ↑ Louis, p. 27 - At the time, amateur boxing could earn a boxer 25 dollars for a win and 7 dollars for a loss.

- ↑ Louis, p. 141

- ↑ Joe Louis vs. the IRS, by Dr. Burton W. Folsom of the Mackinac Center for Public Policy, July 7, 1997.. Retrieved on 2007-08-02.

Primary Sources

- Joe Louis, Art Rust Jr., and Edna Rust. Joe Louis: My Life (New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1978)

Secondary Sources

- Jakoubek, Robert. Joe Louis (New York: Chelsea House, 1990)

- Lipsyte, Robert. Joe Louis: A Champ for All America (New York: Harper Collins, 1994)

- Margolick, David. Beyond Glory: Joe Louis vs. Max Schmeling, and a World on the Brink (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2005)

- Myler, Patrick. Ring of Hate (New York: Arcade, 2005)