Amphiboly: Difference between revisions

imported>Subpagination Bot m (Add {{subpages}} and remove any categories (details)) |

imported>John Pate (Included real trees instead of bracketed text to illustrate sentences) |

||

| Line 8: | Line 8: | ||

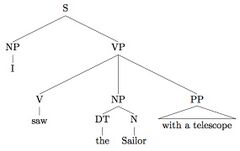

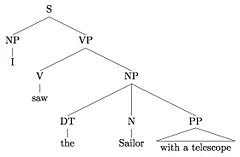

obtains two possible constituent structures: | obtains two possible constituent structures: | ||

[[Image: Amphiboly1.jpg|240px|Figure 1]] and [[Image: Amphiboly2.jpg|240px|Figure 2]] | |||

The structure from Figure 1 portrays ego seeing the sailor by using a telescope, whereas the structure from figure 2 portrays ego seeing the sailor holding a telescope and not, for example, the sailor holding a banana. | |||

[[Parsing]] with any remotely realistic natural language grammar either devised by hand or extracted from [[Corpus linguistics|corpora]] usually yields several constituent structures for each sentence, and so one of the chief occupations of [[computational linguistics]] is determining which of the constituent structures found corresponds to the intended reading. Moreover, as humans usually agree on which of the constituent structures is correct with very little effort, [[psycholinguistics|psycholinguists]] investigate which factors prompt the selection of one constituent structure over another. | [[Parsing]] with any remotely realistic natural language grammar either devised by hand or extracted from [[Corpus linguistics|corpora]] usually yields several constituent structures for each sentence, and so one of the chief occupations of [[computational linguistics]] is determining which of the constituent structures found corresponds to the intended reading. Moreover, as humans usually agree on which of the constituent structures is correct with very little effort, [[psycholinguistics|psycholinguists]] investigate which factors prompt the selection of one constituent structure over another. | ||

Revision as of 23:29, 16 November 2007

Amphiboly is the phenomenon wherein one sentence (or, more generally, one string of symbols) in a language obtains two or more constituent structures (see syntax) according to one grammar. This leads to ambiguity. In natural languages, each constituent structure typically corresponds to a different meaning. For example, in English, the sentence

"I saw the sailor with a telescope"

obtains two possible constituent structures:

The structure from Figure 1 portrays ego seeing the sailor by using a telescope, whereas the structure from figure 2 portrays ego seeing the sailor holding a telescope and not, for example, the sailor holding a banana.

Parsing with any remotely realistic natural language grammar either devised by hand or extracted from corpora usually yields several constituent structures for each sentence, and so one of the chief occupations of computational linguistics is determining which of the constituent structures found corresponds to the intended reading. Moreover, as humans usually agree on which of the constituent structures is correct with very little effort, psycholinguists investigate which factors prompt the selection of one constituent structure over another.