World War II, air war: Difference between revisions

imported>Howard C. Berkowitz m (Continuing splits) |

imported>Howard C. Berkowitz (links) |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{subpages}} | {{subpages}} | ||

{{seealso|World War II, | {{seealso|World War II, air war, German European offensive}} | ||

{{seealso|Battle of Britain}} | {{seealso|Battle of Britain}} | ||

{{seealso|World War II, | {{seealso|World War II, air war, Allied offensive counter-air campaign}} | ||

{{seealso|World War II, | {{seealso|World War II, air war, Southwest Pacific}} | ||

{{seealso|World War II, | {{seealso|World War II, air war, European Theater Strategic Operations}} | ||

{{seealso|Battle of the Atlantic}} | {{seealso|Battle of the Atlantic}} | ||

{{seealso|World War II, | {{seealso|World War II, air War, Mediterranean and European tactical operations}} | ||

{{seealso|World War II, | {{seealso|World War II, air war, Pacific Theater Strategic Operations}} | ||

{{seealso|World War II, | {{seealso|World War II, air war, nuclear warfare}} | ||

{{seealso|Strategic bombing, ethics and deterrence}} | {{seealso|Strategic bombing, ethics and deterrence}} | ||

While there are arguments about the starting date of the ''[[Second World War]]'', there is little question that on several of the dates most often suggested, '''air warfare''' was a major part. On December 12, 1937, Japanese aircraft sank the U.S. [[river gunboat]], ''USS Panay''. When Germany executed its [[Case White]] and invaded [[Poland]], on September 1, 1939, the most mobile of the German force fought a [[combined arms]] campaign in which both [[close air support]] and [[battlefield air interdiction]] played critical parts. Early on the morning of December 7, 1941, Japanese aircraft initiated the [[Battle of Pearl Harbor]], and, in the next days, made more stunning attacks, such as at [[Clark Field]] in the [[Phillippines]]. | While there are arguments about the starting date of the ''[[Second World War]]'', there is little question that on several of the dates most often suggested, '''air warfare''' was a major part. On December 12, 1937, Japanese aircraft sank the U.S. [[river gunboat]], ''USS Panay''. When Germany executed its [[Case White]] and invaded [[Poland]], on September 1, 1939, the most mobile of the German force fought a [[combined arms]] campaign in which both [[close air support]] and [[battlefield air interdiction]] played critical parts. Early on the morning of December 7, 1941, Japanese aircraft initiated the [[Battle of Pearl Harbor]], and, in the next days, made more stunning attacks, such as at [[Clark Field]] in the [[Phillippines]]. | ||

Revision as of 19:05, 20 August 2008

- See also: World War II, air war, German European offensive

- See also: Battle of Britain

- See also: World War II, air war, Allied offensive counter-air campaign

- See also: World War II, air war, Southwest Pacific

- See also: World War II, air war, European Theater Strategic Operations

- See also: Battle of the Atlantic

- See also: World War II, air War, Mediterranean and European tactical operations

- See also: World War II, air war, Pacific Theater Strategic Operations

- See also: World War II, air war, nuclear warfare

- See also: Strategic bombing, ethics and deterrence

While there are arguments about the starting date of the Second World War, there is little question that on several of the dates most often suggested, air warfare was a major part. On December 12, 1937, Japanese aircraft sank the U.S. river gunboat, USS Panay. When Germany executed its Case White and invaded Poland, on September 1, 1939, the most mobile of the German force fought a combined arms campaign in which both close air support and battlefield air interdiction played critical parts. Early on the morning of December 7, 1941, Japanese aircraft initiated the Battle of Pearl Harbor, and, in the next days, made more stunning attacks, such as at Clark Field in the Phillippines.

The first key blows in Western Europe included an air assault on the seemingly impregnable fortress of Eben Emael After closely coupled air and armored warfare smashed across France, German air forces were unable to stop the desperate evacuation from Dunkirk, and Germany realized that they would need to invade the United Kingdom to prevail. When the German Army Heer and Navy Kriegsmarine insisted on air supremacy over the English Channel, the Battle of Britain was Germany's first strategic defeat.

During the Battle of Britain, and indeed likely in response to a small British raid on Berlin, both sides began city bombing. This was not a new form of warfare, as Pablo Picasso's memorable painting of Guernica,Spain illustrated. Systematic strategic bombing, primarily by the Allies, was a significant early in the European theater of operations, and much of the "island-hopping" strategy of the U.S. in the Pacific theater was to gain bomber bases in Japan. The U.S. would never fight the Mahanian decisive battleship engagement in the Western Pacific, the assumption of early Japanese strategists on how Japan would prevail. Strategic bombing, while important, was not as decisive as early air theorists suggested, although it may have been war-ending with the nuclear attacks on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Postwar analysis showed how strategic bombing could have been more effective, but it is highly questionable that even the wisest use of WWII technology could have had a far more decisive role.

Transport aircraft, flying through the "Hump" of the Himalayas, above the planned ceiling of the aircraft, let cut-off troops in the China-Burma-India theater remain a threat to the Japanese.

Many technologies first seen in this war were still experimental. Some were effective. Others were marginally effective but took resources better used elsewhere. Some were, for various reasons, kept out of production and combat until too late. Some efforts were not mere failures, but the stuff of engineering legend.

"During the human struggle between the British and the German Air Forces, between pilot and pilot, between AAA batteries and aircraft, between ruthless bombing and fortitude of the British people, another conflict was going on, step by step, month by month. This was a secret war, whose battles were lost or won unknown to the public, and only with difficulty comprehended, even now, to those outside the small scientific circles concerned. Unless British science had proven superior to German, and unless its strange, sinister resources had been brought to bear in the struggle for survival, we might well have been defeated, and defeated, destroyed." — Winston Churchill[1]

Radar was an early and critical development, but the rather primitive British radar would have been useless had it not been part of an efficient integrated air defense system. German bombers used electronic navigation aids; Britain countered with the beginnings of electronic warfare. Germany introduced the first cruise missile, the [V-1] and the first ballistic missile, the V-2. Japan introduced the first guided, sea-skimming anti-shipping missile, the kamikaze, and the Allied proximity fuze may have been the decisive edge in defense.

Mathematicians and statisticians had a vital role; what we now call operations research was originally military operations research; the beginnings of modern control system theory included Norbert Wiener's work in controlling antiaircraft. Group theory and other mathematical esoterica were at the heart of the most critical communications intelligence of the war. Targeting was in its infancy, but, had cryptanalysis and operations research convinced top bomber commanders of their findings, concentration on the German petroleum industry might have ended the European war much earlier.

Bomber survival over Germany became more and more difficult until the P-51, a culmination of propeller-driven aircraft powered by reciprocating motors, began escorting. Nevertheless, had Hitler given more resources to the first practical jet fighter, the Me-262, it could have made a massive difference.

Air Power and Germany: The Luftwaffe

The Luftwaffe, the German Air Force, was the pride of Nazi Germany under its bombastic leader Hermann Goering, it learned new combat techniques in the Spanish Civil War and appealed to Hitler as the decisive strategic weapon he needed. Its high technology and rapid growth led to exaggerated fears in the 1930s that cowed the British and French into appeasement. In the war the Luftwaffe performed well in 1939-41, but was poorly coordinated with overall German strategy, and never ramped up to the size and scope needed in a total war. It never built large bombers, was deficient in radar, and could not deal with the faster, more agile P-51 Mustang pursuit planes after 1943. The Luftwaffe was narrowly defeated in the Battle of Britain (1940), and reached maximum size pf 1.9 million airmen in 1942. Grueling operations wasted it away on the eastern front after 1942. It lost most of its fighter planes to Mustangs in 1944 while trying to defend against massive American and British air raids. When its gasoline supply ran dry in 1944, it was reduced to anti-aircraft artillery, for which the German term was "flak", and many of its men were sent to infantry units.

Luftwaffe's Bombing Failure

The uses made of air power depend primarily on doctrine. This is clear from the failure of the Germans, Japanese and Soviets to build long-range strategic bombers. Germany had short- range bombers, but lacking a clear doctrine of how to use them it lost the "Battle of Britain" in late summer 1940. The Luftwaffe started by successfully attacking radar stations, command posts, airfields and fighter planes--a strategy that was on the verge of gaining complete and permanent air supremacy. Hitler, enraged when the RAF bombed Berlin, ordered the Luftwaffe to switch to bombing civilians (the "Blitz"). Thousands died but British morale never faltered. The RAF rebuilt its fighter strength and soon cleared British airspace of the Luftwaffe. The Luftwaffe could bomb and strafe, but was unprepared to defend itself against Spitfires and Hurricanes. Hitler's invasion of Britain required air superiority, so it had to be canceled. On the eastern front, Hitler expected the blitzkrieg to work so quickly that strategic bombing of Russian munitions factories would be unnecessary. By the time the Luftwaffe realized the necessity of hitting those factories, reverses on the ground put them out of range.

In the Mediterranean, the Luftwaffe tried to defeat the invasions of Sicily and Italy with tactical bombing. They failed because the Allied air forces systematically destroyed most of their air fields, and because by 1943 German pilots were so poorly trained that they could scarcely handle large planes. The Luftwaffe threw everything it had against the Salerno beachhead, but was outgunned ten to one, and then lost the vital airfields at Foggia.[2] After that it had only one success in Italy, a devastating raid on the American supply depot at Bari, in December, 1943. (Only 30 out of 100 bombers got through, but one found an ammunition ship.) The Germans ferociously opposed the American landing at Anzio in February, 1944, but the Luftwaffe was outnumbered 5 to 1 and so totally outclassed in equipment and skill that it inflicted little damage. Italian air space belonged to the Allies, and the Luftwaffe's strategic capability was zilch.

Air Power and Britain

- See also: Battle of Britain

Air superiority or supremacy was a prerequisite to Operation Sea Lion, the German amphibious invasion of Britain. German amphibious warfare tactics and capabilities were primitive, and the German Army and Navy believed an invasion could succeed only if the German Air Force could guarantee the Royal Navy would not be able to attack the landing force. To do so, the Royal Air Force had to be defeated.To achieve this, the Luftwaffe battled British air defense after the fall of France, from August to September 1940.

The Luftwaffe used 1300 medium bombers guarded by 900 fighters; they made 1500 sorties a day from bases in France, Belgium and Norway. The Germans immediately pulled out their Ju-87 Stukas, which were too vulnerable to modern fighters. The RAF had 650 fighters, with more coming out of the factories every day. Thanks to its new radar system, tightly coordinated with fighters, anti-aircraft artillery, and other defenses, the British knew where the Germans were, and could concentrate their counterattacks.

At first, and with the greatest danger to the British, Germans used their strategic bombing doctrine to focus on RAF airfields and radar stations. After the RAF bomber forces (quite separate from the fighter forces) attacked Berlin and other cities, Hitler swore revenge and diverted the Luftwaffe to attacks on London.

The success the Luftwaffe was having in rapidly wearing down the RAF was squandered, as the civilians being hit were far less critical than the airfields and radar stations that were now ignored. London was not a factory city and aircraft production went up.The last German daylight raid was September 30; the Luftwaffe was taking unacceptable losses and broke off the attack; occasional blitz raids hit London and other cities from time to time before May 1941, killing some 43,000 civilians. The Luftwaffe lost 1733 planes, the British, 915. The British showed more determination, better radar, and better ground control, while the Germans violated their own doctrine with wasted attacks on London.

The British surprised the Germans with their high quality airplanes; flying close to home bases where they could refuel, and using radar as part of an integrated air defense system (IADS), they had a significant advantage over German planes operating at long range. The Hawker Hurricane fighter plane played a vital role for the Royal Air Force (RAF) in winning the Battle of Britain in the summer of 1940. A fast, heavily armed monoplane that went into service in 1937, the Hurricane was effective against both German fighters and bombers and accounted for 70-75% of German losses during the battle. The Battle of Britain showed the world that Hitler's vaunted war machine could be defeated.

Churchill's tribute to the Royal Air Force is eloquent:

Never, in the course of human events, have so many, owed so much, to so few.

.

Britain still faced starvation if the Battle of the Atlantic could not be won, and there was a long road ahead to defeating the Nazis and any possible invasion in the future.

British airpower was sigificant in North Africa, and, when the strategic bombing campaign against Germany began in earnest, it was an around-the-clock effort, with British bombers at night and U.S. aircraft during the day. The aircraft, tactics, and doctrines were different; there is argument how complementary they were in achieving strategic effect.

Air Power and the U.S.

The stunning success of the Luftwaffe's Ju-87 Stuka dive bombers in the blitzkriegs that shattered Poland in 1939 and France in 1940, proved to civilians that air power would dominate the battlefield, leaving the infantry far behind. The US Army was reluctant to draw that conclusion, but it was dumbfounded by the performance of the Stukas acting as a highly mobile, highly effective strike force--a super artillery.

To defend against the Luftwaffe the Army decided to vastly expand the anti-aircraft units provided by the otherwise obsolete Coast Artillery branch, creating the air defense artillery branch. Airmen retorted the only solution was to build better planes that would shoot the Stukas down and gain control of the air. Airmen felt strongly that only they understood the enormous potential of air power, and that their vision was being held back. They dreamed of complete independence, noting that Germany's Luftwaffe and Britain's Royal Air Force (RAF) had long been disentangled from the old-fashioned, narrow-minded mud soldiers. The American people, enthusiastic about aviation in exact proportion to their fear of high-casualty trench warfare, and their love affair with modern technology, had long been supportive of a well-funded, independent air force. President Roosevelt sided with public opinion and the aviators. In 1940 he vowed to build 50,000 airplanes a year, far more than the most starry-eyed aviator had ever imagined.

He gave command of the Navy to an aviator, Admiral Ernest King, with a mandate for an aviation-oriented war in the Pacific. FDR allowed King to build up land-based naval and Marine aviation, and seize control of the long-range bombers used in antisubmarine patrols in the Atlantic. Roosevelt basically agreed with Robert Lovett, the civilian Assistant Secretary of War for Air, who argued, "While I don't go so far as to claim that air power alone will win the war, I do claim the war will not be won without it."[3]

Roosevelt rejected proposals for complete independence for the Air Corps, because the old-line generals and the entire Navy were vehemently opposed. In the compromise that was reached everyone understood that after the war the aviators would get their independence. Meanwhile, their status was upgraded from "Army Air Corps" to "Army Air Forces" (AAF) in June, 1941, and they seized almost complete freedom in terms of internal administration. Thus the AAF set up its own medical service independent of the Surgeon General, its own WAC units, and its own logistics system. It had full control over the design and procurement of airplanes and related electronic gear and ordnance. Its purchasing agents controlled 15% of the nation's Gross National Product. Together with naval aviation, it recryuted the best young men in the nation. General Hap Arnold headed the AAF. One of the first military men to fly, and the youngest colonel in World War I, he selected for the most important combat commands men who were ten years younger than their Army counterparts, including Ira Eaker (b. 1896), Jimmy Doolittle (b. 1896), Hoyt Vandenberg (b. 1899), Elwood "Pete" Queseda (b. 1904), and, youngest of them all, Curtis LeMay (b. 1906). Although a West Pointer himself, Arnold did not automatically turn to Academy men for top positions. Since he operated without theater commanders, Arnold could and did move his generals around, and speedily removed underachievers.

Aware of the need for engineering expertise, he went outside the military and formed close liaisons with top engineers like rocket specialist Theodore von Karmen at Cal Tech. Arnold was given seats on the US Joint Chiefs of Staff and the US-British Combined Chiefs of Staff. Arnold, however, was officially Deputy Chief of [Army] Staff, so on committees he deferred to his boss, General Marshall. Thus Marshall made all the basic strategic decisions, which were worked out by his "War Plans Division" (WPD, later renamed the Operations Division). WPD's section leaders were infantrymen or engineers, with a handful of aviators in token positions.

The AAF had its own planning division, whose advice was largely ignored by WPD. Airmen were also underrepresented in the planning divisions of the Joint Chiefs of Staff and of the Combined Chiefs. Aviators were largely shut out of the decision-making and planning process because they lacked seniority in a highly rank-conscious system. The freeze intensified demands for independence, and fueled a spirit of "proving" the superiority of air power doctrine. Because of the young, pragmatic leadership at top, and the universal glamor accorded aviators, morale in the AAF was strikingly higher than anywhere else (except perhaps Navy aviation.)

The AAF provided extensive technical training, promoted officers and enlisted faster, provided comfortable barracks and good food, and was safe. The only dangerous jobs were voluntary ones as crew of fighters and bombers--or involuntary ones at jungle bases in the Southwest Pacific. Marshall, an infantryman uninterested in aviation before 1939, became a partial convert to air power and allowed the aviators more autonomy. He authorized vast spending on planes, and insisted that American forces had to have air supremacy before taking the offensive. However, he repeatedly overruled Arnold by agreeing with Roosevelt's requests in 1941-42 to send half of the new light bombers and fighters to the British and Soviets, thereby delaying the buildup of American air power.

The Army's major theater commands were given to infantrymen Douglas MacArthur and Dwight D. Eisenhower. Neither had paid much attention to aviation before the war (though Ike learned to fly). By 1942 both had become air power enthusiasts, and built their strategies around the need for tactical air supremacy. MacArthur had been badly defeated in the Philippines in 1941-42 primarily because the Japanese controlled the sky. His planes were outnumbered and outclassed, his airfields shot up, his radar destroyed, his supply lines cut. His infantry never had a chance. MacArthur vowed never again. His island hopping campaign was based on the strategy of isolating Japanese strongholds while leaping past them. Each leap was determined by the range of his air force, and the first task on securing an objective was to build an airfield to prepare for the next leap.[4]

Offensive counter-air, to clear the way for strategic bombers and an eventually decisive cross-channel invasion, was a strategic mission led by escort fighters partered with heavy bombers. The tactical mission, however, was the province of fighter-bombers, assisted by light and medium bombers.

Tactical Aviation

Tactical air doctrine stated that the primary mission was to turn tactical superiority into complete air supremacy--to totally defeat the enemy air force and obtain control of its air space. This could be done directly through dogfights, and raids on airfields and radar stations, or indirectly by destroying aircraft factories and fuel supplies. Anti-aircraft artillery (called "ack-ack by the British, "flak" by the Germans, and "Archie" by the Yanks) could also play a role, but it was downgraded by most airmen.

The Allies won air supremacy in the Pacific in 1943, and in Europe in 1944. That meant that Allied supplies and reinforcements would get through to the battlefront, but not the enemy's. It meant the Allies could concentrate their strike forces wherever they pleased, and overwhelm the enemy with a preponderance of firepower. This was the basic Allied strategy, and it worked. Air superiority depended on putting the offensive counter-air force in positions where they fought on terms of maximum advantage. For example, British "Rhubarb" operations exploited bad weather, so they could approach German airfields, shoot down aircraft committed to landing or takeoff, and strafe ground facilities.

In air combat, the RAF demonstrated the importance of speed and maneuverability in the Battle of Britain (August, 1940), when its fast Spitfire fighters easily riddled the clumsy Stukas as they were pulling out of dives. Once the brief chivalry among First World War airmen passed, the best fighter pilots killed their opponents before the opponent ever became aware of them. The race to build the fastest fighter became one of the central themes of World War Two, but not as much as command and control -- having the best planes in the wrong places had no effct. The Japanese lost, because they never advanced beyond the Zero--a great plane in 1941, a loser in 1944.

Amazingly, the Germans "won" the technical race. In the critical year of the air war, 1944, they were flying the fastest, most maneuverable most heavily armed plane of the era, the Messerschmitt Me-262, the first jet. The first British jet appeared a month later; the first US jet was ready in late 1945. However, Hitler sent the ME-262 back to the drawing boards for reconfiguration as a bomber, and it never played a major role in the war. Hitler saw airplanes only as offensive weapons, and his interference prevented the Luftwaffe from acquiring and using enough fighter planes to stop the Allied bombers. By the fall of 1944, the Luftwaffe had virtually disappeared. Hitler instead emphasized ant-aircraft defenses, such as the flak batteries that surrounded all major German cities and war plants, and which consumed a large fraction of all German munitions production in the last year of the war.[5]

Once total air supremacy in a theater was gained the second mission was battlefield air interdiction: stopping flow of enemy supplies and reinforcements in a zone five to fifty miles behind the front. Whatever moved had to be exposed to air strikes, or else confined to moonless nights; World War II radar could not guide ground attack. A large fraction of tactical air power focused on this mission.

The third and lowest priority mission was close air support or direct assistance to ground units on the battlefront by blowing up bunkers, slicing through armor, and mowing down exposed infantry. Airmen disliked the mission because it subordinated the air war to the ground war; furthermore, slit trenches, camouflage, and flak guns usually reduced the effectiveness of close air support. "Operation Cobra" in July, 1944, targeted a critical strip of 3,000 acres of German strength that held up the breakthrough out of Normandy. General Omar Bradley, his ground forces stymied, placed his bets on air power. 1,500 heavies, 380 medium bombers and 550 fighter bombers dropped 4,000 tons of high explosives and napalm. Bradley was horrified when 77 planes bombed short: The ground belched, shook and spewed dirt to the sky. Scores of our troops were hit, their bodies flung from slit trenches. Doughboys were dazed and frightened....A bomb landed squarely on McNair in a slit trench and threw his body sixty feet and mangled it beyond recognition except for the three stars on his collar.[6][7] The Germans were stunned senseless, with tanks overturned, telephone wires severed, commanders missing, and a third of their combat troops killed or wounded. The defense line broke; Joe Collins rushed his VII Corps forward; the Germans retreated in a rout; the Battle of France was won; air power seemed invincible. However, the sight of a senior colleague killed by error was unnerving, and after Cobra Army generals were so reluctant to risk "friendly fire" casualties that they often passed over excellent attack opportunities. Infantrymen, on the other hand, were ecstatic about the effectiveness of close air support:

Air strikes on the way; we watch from a top window as P-47s dip in and out of clouds through suddenly erupting strings of Christmas-tree lights [flak], before one speck turns over and drops toward earth in the damnest sight of the Second World War, the dive-bomber attack, the speck snarling, screaming, dropping faster than a stone until it's clearly doomed to smash into the earth, then, past the limits of belief, an impossible flattening beyond houses and trees, an upward arch that makes the eyes hurt, and, as the speck hurtles away, WHOOM, the earth erupts five hundred feet up in swirling black smoke. More specks snarl, dive, scream, two squadrons, eight of them, leaving congealing, combining, whirling pillars of black smoke, lifting trees, houses, vehicles, and, we devoutly hope, bits of Germans. We yell and pound each other's backs. Gods from the clouds; this is how you do it! You don't attack painfully across frozen plains, you simply drop in on the enemy and blow them out of existence.[8]

Two-way mobile radio equipment was not good enough for close air support until the last year of the war, when armored divisions assigned airmen to radio-equipped tanks to guide the attacks. In the first days of the Battle of the Bulge, in December 1944, bad weather grounded all planes. When the skies cleared, 52,000 AAF and 12,000 RAF sorties against German positions and supply lines immediately doomed Hitler's last offensive. Patton said the cooperation of XIX TAC Air Force was "the best example of the combined use of air and ground troops that I ever witnessed."[9]On the whole, however, ground forces grumbled endlessly that the AAF was not providing the "help" needed. Complaints escalated when it was noted that Marine Aviation had begun to provide close air support to Marines on the ground.

Close air support for the Army

The workhorse of U.S. tactical air power was the P-47 Thunderbolt, although the British Typhoon was effective; see the P-47 article.

To implement tactical air the United States needed better planes and pilots. The aircraft industry had lagged behind Germany, Britain and even Japan during the 1930s, so the nation entered the war with inferior equipment. At Guadalcanal, the Bell P-400 Aircobras were helpless against superior Japanese planes. They thus became available close air support, to the delight of the mud soldiers. When Stalin asked for 500 additional Lend-Lease planes in 1942, he specified he did not want any more of the Curtiss P-40 Tomahawks, because it "was not up to the mark in the fight against modern German fighter planes." In a frantic technological race against the Nazis, American designers created a series of fighters and bombers that had the speed, climb-rate, maneuverability, and range to do the job.

North Africa 1942-43

- See also: Operation Torch

Eisenhower's first command was the invasion of North Africa in November, 1942, at a time when the Luftwaffe was still strong. One of Ike's corps commanders, General Lloyd Fredendall, used his planes as a "combat air patrol" that circled endlessly over his front lines ready to defend against Luftwaffe attackers. Like most infantrymen, Fredendall assumed that all assets should be used to assist the ground forces. More concerned with defense than attack, Fredendall was soon replaced by Patton.

Likewise the Luftwaffe made the mistake of dividing up its air assets, and failed to gain control of the air or to cut Allied supplies. The RAF in North Africa, under General Arthur Tedder, concentrated its air power and defeated the Luftwaffe. The RAF had an excellent training program (using bases in Canada), maintained very high aircrew morale, and inculcated a fighting spirit. Senior officers monitored battles by radar, and directed planes by radio to where they were most needed.

The RAF's success convinced Eisenhower that its system maximized the effectiveness of tactical air power; Ike became a true believer. The point was that air power had to be consolidated at the highest level, and had to operate almost autonomously. Brigade, division and corps commanders lost control of air assets (except for a few unarmed little "grasshoppers;" observation aircraft that reported the fall of artillery shells so the gunners could correct their aim. With one airman in overall charge, air assets could be concentrated for maximum offensive capability, not frittered away in ineffective "penny packets." Eisenhower--a tanker in 1918 who had theorized on the best way to concentrate armor--recognized the analogy. Split up among infantry in supporting roles tanks were wasted; concentrated in a powerful force they could dictate the terms of battle.

The fundamental assumption of air power doctrine was that the air war was just as important as the ground war. Indeed, the main function of the sea and ground forces, insisted the air enthusiasts, was to seize forward air bases. Field Manual 100-20, issued in July 1943, became the airman's bible for the rest of the war, and taught the doctrine of equality of air and land warfare. The idea of combined arms operations (air, land, sea) strongly appealed to Eisenhower and MacArthur. Eisenhower invaded only after he was certain of air supremacy, and he made the establishment of forward air bases his first priority. MacArthur's leaps reflected the same doctrine. In each theater the senior ground command post had an attached air command post. Requests from the front lines went all the way to the top, where the air commander decided whether to act, when and how. This slowed down response time--it might take 48 hours to arrange a strike--and involved rejecting numerous requests from the infantry for a little help here, or a little intervention there.

Tactical Missions in Europe

As the Luftwaffe disintegrated in 1944, escorting became less necessary and fighters were increasingly assigned to tactical ground-attack missions, along with the medium bombers. To avoid the lethal fast-firing 20mm Oerlikon flak guns, pilots come in fast and low (under enemy radar), made a quick run, then disappeared before the gunners could respond. The main missions were to keep the Luftwaffe suppressed by shooting up airstrips, and to interdict the movement of munitions, oil and troops by blasting away at railway bridges and tunnels, oil tank farms, canal barges, trucks and moving trains. Occasionally a choice target was discovered through intelligence. ULTRA communications intelligence three days after D-Day pinpointed the location of Panzer Group West headquarters. A quick raid destroyed its radio gear and killed many key officers, ruining the Germans' ability to coordinate a panzer counterattack against the beachheads.

In Europe after D-Day the Air Force averaged 1,300 light bomber crews and 4,500 fighter pilots. They claimed destruction of 86,000 railroad cars, 9,000 locomotives, 68,000 trucks, and 6,000 tanks and armored artillery pieces. Thunderbolts alone dropped 120,000 tons of bombs and thousands of tanks of napalm, fired 135 million bullets and 60,000 rockets, and claimed 3,916 enemy planes killed. Beyond the destruction itself, the appearance of unopposed Allied fighter-bombers ruined morale, as privates and generals alike dived for the ditches. Field Marshal Erwin Rommel, for example, was seriously wounded in July, 1944, when he dared to ride around France in the daytime. The commander of the elite 2nd Panzer Division fulminated:

They have complete mastery of the air. They bomb and strafe every movement, even single vehicles and individuals. They reconnoiter our area constantly and direct their artillery fire....The feeling of helplessness against enemy aircraft has a paralyzing effect, and during the bombing barrage the effect on inexperienced troops is literally 'soul-shattering.'[10]

Tactical issues in the Pacific

General George Kenney, in charge of tactical air power under MacArthur, never had enough planes, pilots or supplies. He was not allowed any authority whatever over the Navy's carriers. But the Japanese were always in worse shape--their equipment deteriorated rapidly because of poor airfields and incompetent maintenance. The Japanese had excellent planes and pilots in 1942, but ground commanders dictated their missions and ignored the need for air superiority before any other mission could be attempted.

Theoretically, Japanese doctrine stressed the need to gain air superiority, but the infantry commanders repeatedly wasted air assets defending minor positions. When Arnold, echoing the official Army line, stated the Pacific was a "defensive" theater, Kenney retorted that the Japanese pilot was always on the offensive. "He attacks all the time and persists in acting that way. To defend against him you not only have to attack him but to beat him to the punch."

Key to Kenney's strategy was the neutralization of bypassed strongpoints like Rabaul and Truk through repeated bombings. One obstacle was "the kids coming here from the States were green as grass. They were not getting enough gunnery, acrobatics, formation flying, or night flying." So he set up extensive retraining programs. The arrival of superior fighters, especially the twin-tailed P-38 Lightning, gave the Americans an edge in range and performance. Occasionally a ripe target appeared, as in the Battle of the Bismark Sea (March, 1943) when bombers sank a major convoy bringing troops and supplies to New Guinea. That success was no fluke. High-flying bombers almost never could hit moving ships. Kenney solved that weakness by teaching pilots the effective new tactic of flying in close to the water then pulling up and lobbing bombs that skipped across the water and into the target.[11]

Supplies were always short in the Southwest Pacific--one enterprising supply sergeant on Guadalcanal ordered engine gaskets from Sears, and thanks to the highly efficient mail service received them quicker than through regular channels. Kenney finally rationalized the supply system, but had no good solution to the lack of reinforcements. Airmen flew far more often in the Southwest Pacific than in Europe, and although rest time in Australia was scheduled, there was no fixed number of missions that would produce transfer back to the states. Coupled with the monotonous, hot, sickly environment, the result was bad morale that jaded veterans quickly passed along to newcomers. After a few months, epidemics of combat fatigue would drastically reduce the efficiency of units. The men who had been at jungle airfields longest, the flight surgeons reported, were in bad shape:

Many have chronic dysentery or other disease, and almost all show chronic fatigue states. . . .They appear listless, unkempt, careless, and apathetic with almost masklike facial expression. Speech is slow, thought content is poor, they complain of chronic headaches, insomnia, memory defect, feel forgotten, worry about themselves, are afraid of new assignments, have no sense of responsibility, and are hopeless about the future. [12]

Marine Aviation: Reluctant Ground Support

The Marines had their own land-based aviation, built around the excellent Chance Vought F4U Corsair, an unusually big fighter-bomber. By 1944. 10,000 Marine pilots operated 126 combat squadrons. Marine Aviation originally had the mission of close air support for ground troops, but it dropped that role in the 1920s and 1930s and became a junior component of naval aviation. The new mission was to protect the fleet from enemy air attacks.

Marines were too lightly armed to employ the sort of heavy artillery barrages and massed tank movements the Army used to clear the battlefield. They relied on aggressiveness and speed; Marines might well make frontal attacks while Army troops waited for artillery preparation.

The Japanese were so well dug in that Marines often needed air strikes on positions 300 to 1,500 yards ahead. Naval gunfire could help at times, but the flat trajectories of naval guns were not optimal for plunging into land fortifications. The Marines pioneered control of fire support, both air and naval gunfire, through various doctrinal revisions, but eventually with a function that continues today, the Air Naval Gunfire Liaison Company.

This reflected the long-held Marine commitment that every member of the Corps, from commandant to pilot to company clerk, absolutely had to be proficient as a rifleman and understand ground conditions. There was an enormous difference in the understanding of a Marine pilot qualified to lead the infantry he was supporting, and Navy and Air Corps pilots with little understanding of close-range ground combat. The Marine formula increased responsiveness, reduced "friendly" casualties, and (flying weather permitting) substituted well for the missing armor and artillery.

Engineers Bulldoze New Airfields

Arnold correctly anticipated that he would have to build forward airfields in inhospitable places. Working closely with the Army Corps of Engineers, he created Aviation Engineer Battalions that by 1945 included 118,000 men. Runways, hangers, radar stations, power generators, barracks, gasoline storage tanks and ordnance dumps had to be built hurriedly on tiny coral islands, mud flats, featureless deserts, dense jungles, or exposed locations still under enemy artillery fire. The heavy construction gear had to be imported, along with the engineers, blueprints, steel-mesh landing mats, prefabricated hangars, aviation fuel, bombs and ammunition, and all necessary supplies. As soon as one project was finished the battalion would load up its gear and move forward to the next challenge, while headquarters inked in a new airfield on the maps.

The engineers opened an entirely new airfield in North Africa every other day for seven straight months. Once when heavy rains along the coast reduced the capacity of old airfields, two companies of Airborne Engineers loaded miniaturized gear into 56 transports, flew a thousand miles to a dry Sahara location, started blasting away, and were ready for the first B-17 24 hours later. Often engineers had to repair and use a captured enemy airfield. The German fields were well-built all-weather operations; by contrast the Japanese installations were ramshackle affairs with poor siting, poor drainage, scant protection, and narrow, bumpy runways. Engineering was a low priority for the offense-minded Japanese, who chronically lacked adequate equipment and imagination.[13]

Strategic Bombing

Anglo-American

British and American strategic bombing advocates had different paradigms of what is, today, called strategic strike. This resulted in different aircraft designs, training, targeting, and operational techniques.

The Pacific operation was essentially American. While there was a generally shared doctrinal concept, the problems of conducting effective strategic bombing was different: the supporting actor award went to the amphibious warriors of the United States Navy, United States Marine Corps, and United States Army, who captured and rebuilt the airfields needed to reach the Japanese home islands.

Had the war in Europe lasted longer, although some claim the nuclear weapons were saved, for "racial" reasons, against Japan, had the weapons been ready and there was not the same confidence in ground victory, they would have been used. For that reason, the article World War II, Air War, nuclear warfare deals first with the concept of nuclear warfare as then understood and the Manhattan Project to develop them. It deals with the decision to use them on Japan, and the mechanics of that operation, because Japan was the only available target when the first bombs were available.

Russian

German

The most basic reason that Germany achieved little in strategic bombing was that they never produced quantities of an appropriate heavy bomber. Early in the war, they had excellent tactical aviation, but when they first faced an integrated air defense system, their essentially medium bombers did not have the numbers or bombload to do major damage to Great Britain.

No power on either side had, even on the drawing boards, anything, bomber or missile, that could have delivered more than a nuisance raid on the United States. The only, and very minor, air attacks on the United States came from Japanese balloons and submarine-launched floatplanes.

German submarine warfare against the United States (Operation Drumbeat), in the early part of the war, however, was significant.

Manned bombers

Failure of German secret weapons

Hitler tried to sustain morale by promising that "secret weapons" would turn the war around. He did indeed have the weapons. The first of 9,300 V-1 flying bombs hit London in mid- June, 1944, and together with 1,300 V-2 rockets caused 8,000 civilian deaths and 23,000 injuries. Although they did not seriously undercut British morale or munitions production, they bothered the British government a great deal--Germany now had its own unanswered weapons system. Using proximity fuzes, British ack-ack gunners (many of them women) learned how to shoot down the 400 mph V-1s; nothing could stop the supersonic V-2s. The British government, in near panic, demanded that upwards of 40% of bomber sorties be targeted against the launch sites, and got its way in "Operation CROSSBOW." The attacks were futile, and the diversion represented a major success for Hitler. In early 1943 the strategic bombers were directed against U- boat pens, which were easy to reach and which represented a major strategic threat to Allied logistics. However, the pens were very solidly built--it took 7,000 flying hours to destroy one sub there, about the same effort that it took to destroy one-third of Cologne. The antisubmarine campaign thus was a victory for Hitler.[14]

Every raid against a V-1 or V-2 launch site was one less raid against the Third Reich. On the whole, however, the secret weapons were still another case of too little too late. The Luftwaffe ran the V-1 program, which used a jet engine, but it diverted scarce engineering talent and manufacturing capacity that were urgently needed to improve German radar, air defense, and jet fighters. The German Army ran the V-2 program. The rockets were a technological triumph, and bothered the British leadership even more than the V-1s. But they were so inaccurate they rarely could hit militarily significant targets.

Furthermore, the program used up scarce technical resources that could have gone into the development of air defense weapons like proximity fuzes and "Waterfall," a deadly ground-to-air rocket. The secret weapon of greatest threat to the Allies was the jet plane that could outfly Allied fighters and shoot down bombers. The Messerschmitt ME-262 prototype flew in 1939, but was never given high priority until too late. Hitler never understood air power; his personal interference repeatedly delayed the jets. First he proclaimed they would not be necessary, then insisted they be redesigned as bombers to make retaliation raids against London. The Luftwaffe would have been a much more deadly threat if it built ten thousand jets; it only made one thousand and they rarely flew combat missions.

Destroying Germany's Oil and Transportation

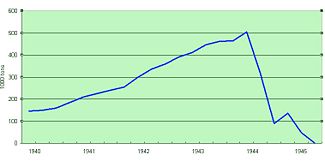

Besides knocking out the Luftwaffe, the second most striking achievement of the strategic bombing campaign was the destruction of the German oil supply. Oil was essential for U-boats and tanks, while very high quality aviation gasoline was essential for piston planes.[15] Germany had few wells, and depended on imports from Russia (before 1941) and Nazi ally Romania, and on synthetic oil plants that used chemical processes to turn coal into oil. Heedless of the risk of Allied bombing, the Germans had carelessly concentrated 80% of synthetic oil production in just 20 plants. These became a top priority for the AAF and RAF in 1944, and were targets for 210,000 tons of bombs. The oil plants were very hard to hit, but also hard to repair. As graph #1 shows, the bombings dried up the oil supply in the summer of 1944. An extreme oil emergency followed, which grew worse month by month.

The third notable achievement of the bombing campaign was the degradation of the German transportation system--its railroads and canals (there was little truck traffic.) In the two months before and after D-Day the American Liberators (B-24), Flying Fortresses and British Lancasters hammered away at the French railroad system. Underground Resistance fighters sabotaged some 350 locomotives and 15,000 freight cars every month. Critical bridges and tunnels were cut by bombing or sabotage. Berlin responded by sending in 60,000 German railway workers, but even they took two or three days to reopen a line after heavy raids on switching yards. The system deteriorated quickly, and it proved incapable of carrying reinforcements and supplies to oppose the Normandy invasion. To that extent the assignment of strategic bombers to the tactical job of interdiction was successful. When Bomber Command hit German cities, it inevitably hit some railroad yards. The AAF made railroad yards a high priority, and gave considerable attention as well to bridges, moving trains, ferries, and other choke points. The "transportation policy" of targeting the railroad system came in for intense debate among Allied strategists. It was argued that enemy had the densest and best operated railway system in the world, and one with a great deal of slack. The Nazis systematically looted rolling stock from conquered nations, so they always had plenty of locomotives and freight cars. Furthermore, most traffic was "civilian," and urgent troop train traffic would always get through. The critics exaggerated the resilience of the German system. As wave after wave of bombers blasted away, repairs took longer and longer. Delays became longer and more frustrating. Yes, the troop trains usually got through, but the "civilian" traffic that did not get through comprised food, uniforms, medical equipment, horses, fodder, tanks, fuel, howitzers, flak shells and machine guns for the front lines, and coal, steel, spare parts, subassemblies, and critical components for munitions factories. By January, 1945, the transportation system was cracking in dozens of places, and front-line units had more luck trying to capture Allied weapons than waiting for fresh supplies of their own.

Unanswered Weapons Systems

Germany and Japan were burned out and lost the war in large part because of strategic bombing. Targeting became somewhat more accurate in 1944, but the real solution to inaccurate bombs was more of them. The AAF dropped 3.5 million bombs (500,000 tons) against Japan, and 8 million (1.6 million tons) against Germany.

The RAF expended about the same tonnage against Germany; Navy and Marine bombs against Japan are not included, nor are the two atomic bombs. While it can be calculated that strategic bombing cost the US and Britain more money than it cost Germany, that calculation is irrelevant. The Allies had plenty of money. The cost of the US tactical and strategic air war against Germany was 18,400 planes lost in combat, 51,000 dead, 30,000 POWs, and 13,000 wounded. Against Japan, the AAF lost 4,500 planes, 16,000 dead, 6,000 POWs, and 5,000 wounded; Marine Aviation lost 1,600 killed, 1,100 wounded. Naval aviation lost several thousand dead.

One fourth of the German war economy was neutralized because of direct bomb damage, the resulting delays, shortages and roundabout solutions, and the spending on anti-aircraft, civil defense, repair, and removal of factories to safer locations. The raids were so large and so often repeated that in city after city the repair system broke down. In 1944 the bombing prevented the full mobilization of the German economic potential. Speer and his staff were brilliant in improvising solutions and work-arounds, but their challenge became more difficulty every week as one backup system after another broke down. By March, 1945, most of Germany's factories, railroads and telephones had stopped working; troops, tanks, trains and trucks were immobilized. With all their great cities crumbling into rubble, with the awareness the Allies had a weapons system they could not answer, Germans suddenly realized they were going to lose the war. In February, 1945, General Marshall overruled the ethical objections of Air Force commanders and ordered a terror attack on Berlin. It was designed to help the Soviet advance and to convince the Nazis their cause was hopeless; 2,900 died (both sides exaggerated the total to 25,000 for propaganda purposes.) Josef Goebbels, Hitler's bloodthirsty propaganda minister, was disconsolate when his beautiful ministry buildings were totally burned out: "The air war has now turned into a crazy orgy. We are totally defenseless against it. The Reich will gradually be turned into a complete desert." By July, 1945, Japan was almost totally shut down. The American and British airmen had achieved the goals of strategic bombing--but neither Berlin nor Tokyo would surrender. The Nazis quit when the Soviets smashed Berlin in the bloodiest battle of the war. The Japanese surrender will be considered later.

References

- ↑ Churchill, Winston (2005). The Second World War, Volume 2: Their Finest Hour. Penguin Books Ltd. ISBN 0141441739.

- ↑ Foggia became the major base of the 15th Air Force. Its 2,000 heavy bombers hit Germany from the south while the 4,000 heavies of the 8th Air Force used bases in Britain, along with 1,300 RAF heavies. While bad weather in the north often canceled raids, sunny Italian skies allowed for more action.

- ↑ Walter Isaacson and Evan Thomas, The Wise Men: Six Friends and the World They Made (1997) p. 203 online

- ↑ .. Quesada 41 (1948): our doctrine = "attainment of...air supremacy as a prerequisite for a major surface campaign"

- ↑ Overy, Air War 121

- ↑ Bradley 280

- ↑ Craven, Wesley F., et al. (1983 1983), The Army Air Forces in World War II. Volume 3. Europe: Argument to V-E Day, January 1944 to May 1945, Office of Air Force History, ADA440398 p. 234

- ↑ Brendan Phibbs, The Other Side of Time: A Combat Surgeon in World War II (1987) p 149

- ↑ Craven, p. 272

- ↑ Craven, p. 227, p. 235

- ↑ Kenney, Kenney Reports 112; Leary, We Shall Return p 99; Quesada 39

- ↑ A. Mae Mills Link and Hubert A. Coleman, Medical Support (1955) 851;

- ↑ Craven, p. 250,253

- ↑ Webster & Franklin, 4:24

- ↑ Jet planes ran on cheap kerosene, and rockets used plain alcohol; the railroad system used coal, which was in abundant supply.