U.S. Progressive Party 1912

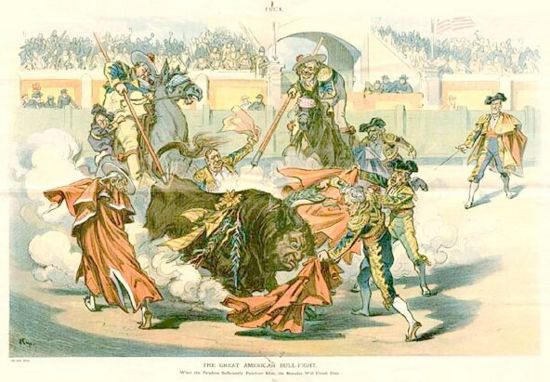

The Progressive Party of 1912 (nicknamed the Bull Moose Party) was an American political party created by a split in the Republican Party in the presidential election of 1912. It was named after the era of reform that people were already calling the Progressive Era. It was organized by Theodore Roosevelt when he lost the Republican nomination to William Howard Taft and pulled his delegates out of the convention. Roosevelt lost in 1912 and while a few local candidates were elected, by 1914 the party virtually collapsed.

Birth of a new party

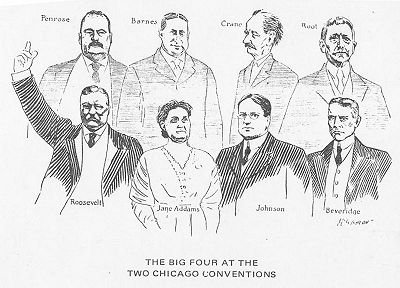

After walking out on the Republican Convention and forming the new Progressive Party, President Roosevelt, when suggested by reporters that he was no longer fit for the office, retorted "I'm as fit as a bull moose" (giving the new party its nickname), and he called his own convention and nominated a national ticket with California Governor Hiram Johnson as his vice-presidential running mate. State parties also nominated slates in most northern states. The platform echoed Roosevelt's 1907-08 proposals, calling for vigorous government intervention to protect the people from the selfish interests.

- "To destroy this invisible Government, to dissolve the unholy alliance between corrupt business and corrupt politics is the first task of the statesmanship of the day." - 1912 Progressive Party Platform[1]

The great majority of Republican governors, congressmen, editors and state and local leaders refused to join the new party, even if they had supported Roosevelt before. Johnson, the Vice-Presidential nominee, who had been elected Governor in California in 1910, remained a member of the Republican Party because his supporters took control of the GOP in California. However, many independent reformers signed up. Three important activists were Gifford Pinchot and his brother Amos Pinchot and feminist Jane Addams.

Only five of the 15 most prominent progressive Republicans in the Senate endorsed the new party and Roosevelt's candidacy for President; three came out for Wilson. Many of Roosevelt's closest political allies supported Taft, including his son-in-law, Nicholas Longworth. Roosevelt's daughter Alice Roosevelt Longworth stuck with her father, causing a permanent chill in her marriage. For men like Longworth, expecting a future in politics, bolting the Republican party ticket was simply too radical a step. Progressives who did not aspire to elective office often went with Woodrow Wilson.

The party was funded by publisher Frank A. Munsey and its executive secretary George W. Perkins, a leading financier. The platform called for women's suffrage, recall of judicial decisions, easier amendment of the U.S. Constitution, social welfare legislation for women and children, workers' compensation (government payments for accidents on the job), limited injunctions against unions during strikes, farm relief, revision of banking to assure an elastic currency, required health insurance in industry, new high inheritance taxes, higher, new federal income taxes on the rich, and limitation of naval armaments after the U.S. caught up in the naval race. Pacifist Jane Addams, a leading supporter, was stunned to discover she had to endorse a platform that called for the building of two new battleships a year. Perkins, a board member of U.S. Steel corporation, was blamed for blocking an anti-trust plank, thus shocking reformers like Gifford Pinchot who saw Roosevelt as a true trust-buster. The result was a deep split in the new party that was never resolved. Roosevelt's philosophy for the Progressive Party was based around New Nationalism, which was the belief in a strong government to regulate industry and protect the middle and working classes. New Nationalism was paternalistic in direct contrast to Woodrow Wilson's individualistic philosophy of "New Freedom".

Election of 1912

Although Roosevelt outpolled Taft in the popular vote and by a large margin of 88–8 in the electoral vote, the GOP apparatus was undamaged. The split engendered in the Republican vote allowed Woodrow Wilson to win the presidency. Some historians argue that even without the split, Wilson would have won (as he did in 1916). The Progressive party did poorly in the 1914 elections and faded away. Most members, including Roosevelt returned to the Republican Party after the Republicans nominated the more progressively-minded Charles Evans Hughes for President in 1916. From 1916 to 1932 the Taft wing controlled the Republican party and refused to nominate any prominent 1912 Progressives to the Republican national ticket. Finally, Frank Knox was nominated for Vice President in 1936.

Historians speculate that if the Bull Moose Party had run only the Roosevelt presidential ticket, it might have attracted many more Republicans willing to split their ballot. But the progressive movement was strongest at the state level, and, therefore, the new party had to field candidates for governor and state legislature. In Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, the local Republican boss, at odds with state party leaders, joined Roosevelt's cause.

The central problem faced by Progressive Party was that the Democrats were more united and optimistic than they had been in decades. The Bull Moosers fancied they had a chance to elect Roosevelt by drawing out progressive elements from both the Republican and Democratic parties. That dream evaporated in July, when the Democrats nominated their most articulate and prominent progressive, Woodrow Wilson. As a leading educator and political scientist, he qualified as the ideal "expert" to handle affairs of state. At least half the nation's independent progressives flocked to Wilson's camp, both because of Wilson's policies and the expectation of victory. Roosevelt haters, such as LaFollette, also voted for Wilson instead of wasting their vote on Taft who could never win. The most serious problem faced by Roosevelt's third party was money. The business interests who usually funded Republican campaigns distrusted Roosevelt and either did not vote or supported Taft. Lacking a strong party press, the Bull Moosers had to spend most of their money on publicity.

Roosevelt succeeded in defeating the convervative Taft with his progressive message that along with Wilson's progressive program totaled 69% of the popular vote. He did win 4.1 million votes (27%), compared to Taft's 3.5 million (23%). However, Wilson's 6.3 million votes (42%) were enough to garner 435 electoral votes. Roosevelt came in second with 88 electoral votes (more than any third party candidate before or since); Pennsylvania was his only Eastern state; in the Midwest he carried Michigan, Minnesota and South Dakota; in the West, California and Washington; in the South, he did not win any states.

The Democrats gained ten seats in the Senate, just enough to form a majority, and 63 new House seats to solidify their control there. Progressive statewide candidates trailed about 20% behind Roosevelt's vote. Almost all of the Progressive candidates, including Albert Beveridge of Indiana, went down to defeat; the only governor elected was Hiram Johnson, who ran on the regular Republican Party ticket. Only seventeen Bull Moosers were elected to Congress, and perhaps 250 to local office. Outside California, there was no real base to the party beyond the personality of Roosevelt himself.

Roosevelt had scored a second-place finish, but he trailed so far behind Wilson that everyone realized his party would never win the White House. With the poor performance at state and local levels in 1912, the steady defection of top supporters, the failure to attract any new support, and a pathetic showing in 1914, the Bull Moose party disintegrated at the national level, although some state parties remained fairly strong. It did very well in Washington, winning a third of the seats in the state legislature, according to the State Legislature history page. Some leaders, such as Harold Ickes of Chicago, supported Wilson in 1916. Many followed Roosevelt back into the Republican Party, which in 1916 nominated Charles Evans Hughes. The ironies were many: Taft had been Roosevelt's hand-picked successor in 1908 and the split between the two men was ideological. No compromise was possible on issues like the independence of the judiciary. Roosevelt's schism allowed the conservatives to gain control of the Republican party and left Roosevelt and his followers drifting in the wilderness throughout the 1920's before most joined the New Deal Democratic Party coalition of President Franklin D. Roosevelt.

Robert LaFollette broke bitterly with Roosevelt in 1912, but he ran for President on his own ticket in 1924, also named the Progressive Party.

See also

Bibliography

- Brands, H.W. Theodore Roosevelt (2001), biography online edition

- Chace, James. 1912: Wilson, Roosevelt, Taft and Debs--The Election that Changed the Country (2005), popular history. excerpt and text search

- Gable, John A. The Bullmoose Years: Theodore Roosevelt and the Progressive Party (1978).

- Howland, Harold. Theodore Roosevelt and His Times, a Chronicle of the Progressive Movement (1920) online at Gutenberg

- Jensen, Richard. "Democracy, Republicanism and Efficiency: The Values of American Politics, 1885-1930," in Byron Shafer and Anthony Badger, eds, Contesting Democracy: Substance and Structure in American Political History, 1775-2000 (U of Kansas Press, 2001) pp 149-180; online version

- Mowry, George E. Theodore Roosevelt and the Progressive Movement (1946), the standard history

- Mowry, George. The Era of Theodore Roosevelt and the Birth of Modern America, 1900-1912. (1954) general survey of era; online

Primary sources

- Croly, Herbert David. Progressive Democracy (1914), theory full text online

- De Witt, Benjamin P. The Progressive Movement (1915), a comprehensive contemporary history of the era full text online

- Pinchot, Amos R. E. and Helene Maxwell Hooker. History of the Progressive Party, 1912-1916 (1918)