Evidence-based medicine

Evidence-based medicine is "the conscientious, explicit and judicious use of current best evidence in making decisions about the care of individual patients."[1] Alternative definitions are "the process of systematically finding, appraising, and using contemporaneous research findings as the basis for clinical decisions"[2] or "evidence-based medicine (EBM) requires the integration of the best research evidence with our clinical expertise and our patient's unique values and circumstances."[3] Better known as EBM, evidence based medicine has roots in clinical epidemiology and the scientific method, and emerged in the early 1990's in response to discoveries about variations and deficiencies[4] in medical care to help healthcare providers and policy makers evaluate the efficacy of different treatments.

Evidence-based practice is not restricted to medicine: dentistry, nursing and other allied health science are adopting "evidence-based medicine" as well as alternative medical approaches, such as acupuncture[5][6]. Evidence-Based Health Care or evidence-based practice extends the concept of EBM to all health professions, including management[7][8] and policy[9][10][11].

Classification

Two types of evidence-based medicine have been proposed:[12]

- Evidence-based guidelines, EBM at the organizational or institutional level, which involves producing clinical practice guidelines, policy, and regulations;

- Evidence-based individual decision making, EBM as practiced by an individual health care provider when treating an individual patient. There is concern that evidence-based medicine focuses excessively on the physician-patient dyad and as a result miss many opportunities to improve healthcare.[12]

Justification

Part of the justification for EBM is the unreliability about making clinical decisions using heuristics.[13][14]

Steps in EBM

- See also Teaching evidence-based medicine

| The 5 S search strategy[15]

Studies: original research studies that can be found using search engines like PubMed. Synthesis: systematic reviews or Cochrane Reviews. Synopses: in EBM journals, ACP Journal club etc. give brief descriptions of original articles and reviews as they appear . Summaries: in EBM textbooks integrate the best available evidence from syntheses to give evidence-based management options for a health problem. Systems: e.g. computerized decision support systems that link individual patient characteristics to relevant evidence. |

Ask

To "ask" and formulate a well-structured clinical question, i.e. one that is directly relevant to the identified problem, and which is constructed in a way that facilitates searching for an answer. The question should have four 'PICO' elements[16][17]: the patient or problem (P); the medical intervention or exposure (e.g., a cause for a disease) (I); the comparison intervention or exposure (C); and the clinical outcomes (O). The better focused the question is, the more relevant and specific the search for evidence will be.[18]

Acquisition of evidence

| Type of publication | Durability |

|---|---|

| Primary publications | |

| Highly cited studies major scientific journals[19] | The results from one-third are refuted or attenuated within 15 years. |

| Original studies in hepatology[20] | Half-life of truth was 45 years |

| Original studies in surgery[21] | Half-life of truth was 45 years |

| Secondary publications | |

| Systematic reviews[22] | Median survival is 5.5 years. 7% may out of date when published 23% may be out of date within 2 years |

| Practice guidelines by the AHRQ[23] | Half-life of truth was 5.8 years |

| Food and Drug Administration New Drug Approvals[24] | 8% acquire a new black box warning. Half occur within 7 years |

| Food and Drug Administration New Drug Approvals[24] | 3% withdrawn. Half occur within 2 years |

The ability to "acquire" evidence, also called information retrieval, in a timely manner may improve healthcare.[25][26] Unfortunately, doctors may be led astray when acquiring information because of difficulties in selecting best articles[27], or because individual trials may be flawed or their outcomes may not be fully representative.[28]

Research conflicts on the ability of end-users of MEDLINE. One study found that users were almost as likely to misinterpret articles found as correctly interpret them.[28] A second study that was in vitro found that searching for evidence was helpful.[29]

One proposed structure for a comprehensive evidence search is the 5S search strategy,[15] and 6S[30] which starts with the search of "summaries" (textbooks). [31]

Appraisal of evidence

|

The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) [32] grades its recommendations for treatments according to the strength of the evidence and the expected overall benefit (benefits minus harms). Its grades are: A.— Good evidence that the treatment improves health outcomes, and benefits substantially outweigh harms. B.— Fair evidence that the treatment improves health outcomes and that benefits outweigh harms. C.— Fair evidence that the treatment can improve health outcomes but the balance of benefits and harms is too close to justify a general recommendation. D.— Recommendation against routinely providing the treatment to asymptomatic patients. There is fair evidence that [the service] is ineffective or that harms outweigh benefits. I.— The evidence is insufficient to recommend for or against routinely providing [the service]. Evidence that the treatment is effective is lacking, of poor quality, or conflicting and the balance of benefits and harms cannot be determined. The USPSTF also grades the quality of the overall evidence as good, fair or poor: Good: Evidence includes consistent results from well-designed, well-conducted studies in representative populations that directly assess effects on health. Fair: Evidence is sufficient to determine effects on health outcomes, but its strength is limited by the number, quality, or consistency of the individual studies, generalizability to routine practice, or indirect nature of the evidence on health outcomes. Poor: Evidence is insufficient to assess the effects on health outcomes because of limited number or power of studies, flaws in their design or conduct, gaps in the chain of evidence, or lack of information on important health outcomes. |

To "Appraise" the quality of the evidence in a study is very important, as one third of the results of even the most visible medical research is eventually either attenuated or refuted.[19] There are many reasons for this[33]; two of the most common being publication bias[34] and conflict of interest[35] (see article on Medical ethics). These two problems interact, as conflict of interest often leads to publication bias.[36][34] Complicating the appraisal process further, many (if not all) studies contain some design flaws, and even when there are no clear methodological flaws, any outcome of a test that is evaluated by statistical test has a margin of error: this means that some positive outcomes will be "false positives".

Often, only the abstract of an article will be read,[37] but many abstracts contain errors.[38] These are usually errors of omission rather than contradiction, but abstracts often over-emphasise positive findings and neglect to mention limitations.

When abstracts are read, readers may be biased [39] and make illogical conclusions[40].

The initial steps in reading an article are determining what the article's conclusion and whether its conclusion, if valid, is important.[41]

Overall risk in the population in a study can be assessed by examining outcome rr prevalence rates in the control groups.[42]

Automated text mining can help assess the quality of an article.[43]

"Levels of evidence" are used for describing the strength of a research study.[44][45] The Equator network is a collection of standards to improve the reporting of health research. An example is the Consort statement for the reporting of randomized controlled trials.

Guides exist for assessing a body of literature; these are discussed below, Assessing a body of research evidence.

- Common threats to validity

Publication bias

Publication bias is "the influence of study results on the chances of publication [in academic journals] and the tendency of investigators, reviewers, and editors to submit or accept manuscripts for publication based on the direction or strength of the study findings. Publication bias has an impact on the interpretation of clinical trials and meta-analyses. Bias can be minimized by insistence by editors on high-quality research, thorough literature reviews, acknowledgment of conflicts of interest, modification of peer review practices, etc."[46]

Conflict of interest

The presence of a conflict of interest has many effects in medical publishing.

Statistical analysis

Common problems include small sample sizes in subgroup analyses[47], problems of "multiple comparisons" when several outcomes are being assessed, and biasing of study populations by selection criteria.

Problems may arise from interim analyses of randomized controlled trials which may lead to exaggerated estimations of treatment effects.[48][49] [50]

Statistical significance:

The statistical significance of the outcome of a study is often summarized by a "P-value" that expresses the likelihood that an observed difference between treatment groups reflects a true difference in treatment effect; the P value is a calculation of the chance that the observed difference reflects the chance outcome of random sampling. Some have argued that focusing on P values neglects other important sources of knowledge and information that should be used to assess the likely efficacy of a treatment [51] In particular, some argue that the P-value should be interpreted in light of how plausible is the hypothesis based on the totality of prior research and physiologic knowledge.[52][51][53] Bayesian inference formalizes this approach to statistical significance.

Application

It is important to "apply" the best practices found to the correct situation. One common problem in applying evidence is that both patients and healthcare professionals often have difficulties with health numeracy and probabilistic reasoning.[54] Another problem is successful clinical reasoning at the bedside.[55] Successful reasoning is associated with the use of pattern matching [56][57] and recognizing clinical findings that are "pivot" or specific to certain diseases[57]. A third problem is to identify exactly which patients will benefit from the new practices. Extrapolating study results to the wrong patient populations (over-generalization)[58][59][60] and not applying study results to the correct population (under-utilization)[61][62] can both increase adverse outcomes.

The problem of over-generalizating study results may be more common among specialist physicians.[63] Two studies found specialists were more likely to adopt cyclooxygenase 2 inhibitor drugs before the drug rofecoxib was withdrawn by its manufacturers because of its unanticipated adverse effects [64][65]. One of the studies went on to state:

- "using COX-2s as a model for physician adoption of new therapeutic agents, specialists were more likely to use these new medications for patients likely to benefit but were also significantly more likely to use them for patients without a clear indication".[65]

Similarly, orthopedists provide more expensive care for back pain, but without measurably increased benefit compared to other types of practitioners.[66] Some of the reason that subspecialists may be more likely to adopt inadequately studied innovations is that they read from a spectrum of journals that have less consistent quality.[67] Articles from specialty journals have been noted to persist in supporting claims in the medical literature that have been refuted.[68]

The problem of under-utilizing study results may be more common when physicians are practising outside their expertise. For example, specialist physicians are less likely to under-utilize specialty care[69][70], while primary care physicians are less likely to under-utilize preventive care[71][72].

Metrics used in EBM

- Diagnosis

- Causation

- Relative measures

- Odds ratio

- Relative risk ratio

- Relative risk reduction

- Absolute measures

- Absolute risk reduction

- Number needed to treat (NNT)[73]

- Number needed to screen[74]

- Number needed to harm

- Health policy

- Cost per year of life saved[75]

- Cost of Preventing an Event (COPE)[76]. For example, to prevent a major vascular event n a high-risk adult , the number needed to treat is 19, the number of years of treatment are 5, and the daily cost of the generic drug is 68 cents. The COPE is 19 * 5 * ( 365 * .68) which equals $23,579 in the United States.

- Years (or months or days) of life saved. "A gain in life expectancy of a month from a preventive intervention targeted at populations at average risk and a gain of a year from a preventive intervention targeted at populations at elevated risk can both be considered large."[77]

Original research studies: levels of evidence

'Levels of evidence' were first proposed in 1979 bye the Canadian Task Force on the Periodic Health Examination[44] then modified by the American College of Chest Physicians[78][79] to create a framework for judging the strength of research. An example of levels of evidence is, based on prior work[45]:

- Level 1 - Randomized controlled trials

- Level 2 - Cohort studies

- Level 3 - Case control studies

- Level 4 - Case series and case reports. The important role of case reports have been described.[80]

These levels of evidence have been criticized as only representing one of two views of medical science.[81] Vandenbroucke proposes that the two views of medical research are:

- Evaluation of interventions. In this view, the randomized controlled trial is most important.

- Discovery and explanation. In this view, the randomized controlled trial is not supreme and observational studies, subgroup analyses, and secondary analyses are important.

In practice, randomized controlled trials are available to support only 21%[82] to 53%[83] of principal therapeutic decisions.[84] Due to this, evidence-based medicine has evolved to accept lesser levels of evidence when randomized controlled trials are not available.[85]

The Grade Working Group recognizes that assessing medical evidence involves attention to other dimensions than study design, and expanded upon the levels of evidence in 2004.[86][87] These dimensions include: study design; study quality; consistency of study results; and directness (e.g. how close does the research study mirror clinical practice)

Summarizing the evidence

Assessing a body of research evidence

Several systems have been proposed to assess whether a body of research evidence establishes causality.

Koch's postulates[88]

|

In the 1880's Koch proposed postulates (Koch's Postulates) that suggest association.[89] However, even though the postulates focus on establishing casuality among infections diseases, examples have emerged that violate his postulates.[88]

Bradford Hill criteria[90]

|

The Bradford Hill criteria were proposed in 1965 in response to studies of the association between tobacco and lung cancer:[90]

More explicit methods have been proposed by groups such as the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) (see yellow text box above), the American College of Chest Physicians[78][79] and the Grade Working Group[91] The Grade Working Group combines the quality of research studies with their clinical relevance.[86] For example, this allows comparing a randomized control trial in a population that is not exactly like the population of interest versus a cohort study that is from a relevant population. The concept that there are multiple dimensions in assessing evidence has been expanded to a proposal that assessing evidence is not a linear process, but is circular.[92]

Diamond has proposed a method using Bayesian beliefs for assessing medical evidence that categorizes beliefs similarly to how evidence is assessed in the legal system.[93]

The legal system

Systematic review

A systematic review is a summary of healthcare research that involves a thorough literature search and critical appraisal of individual studies to identify the valid and applicable evidence. It often, but not always, uses appropriate techniques (meta-analysis) to combine studies, and may grade the quality of the particular pieces of evidence according to the methodology used, and according to strengths or weaknesses of the study design. While many systematic reviews are based on an explicit quantitative meta-analysis of available data, there are also qualitative reviews which nonetheless adhere to the standards for gathering, analyzing and reporting evidence.

Clinical practice guidelines

Clinical practice guidelines are defined as "Directions or principles presenting current or future rules of policy for assisting health care practitioners in patient care decisions regarding diagnosis, therapy, or related clinical circumstances. The guidelines may be developed by government agencies at any level, institutions, professional societies, governing boards, or by the convening of expert panels. The guidelines form a basis for the evaluation of all aspects of health care and delivery."[94]

Incorporating evidence into clinical care

see also Teaching evidence-based medicine

Medical informatics

Practicing clinicians cite the lack of time for keeping up with emerging medical evidence that may change clinical practice.[95] Medical informatics is an essential adjunct to EBM, and focuses on creating tools to access and apply the best evidence for making decisions about patient care.[3] Before practicing EBM, informaticians (or informationists) must be familiar with medical journals, literature databases, medical textbooks, practice guidelines, and the growing number of other evidence-based resources, like the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews and Clinical Evidence.[95] Similarly, for practicing medical informatics properly, it is essential to have an understanding of EBM, including the ability to phrase an answerable question, locate and retrieve the best evidence, and critically appraise and apply it.[96][97]

Health care quality assurance

Criticisms of EBM

There are a number of criticisms of EBM.[98][99]

Excessive reliance on empiricism and deduction

EBM has been criticized as an attempt to define knowledge in medicine in the same way that was done unsuccessfully by the logical positivists in epistemology, "trying to establish a secure foundation for scientific knowledge based only on observed facts" [100]and not recognizing the fallible nature of knowledge in general.[101] The problem of relying on empiric evidence as a foundation for knowledge was recognized over 100 years ago and is known as the "Problem of Induction" or "Hume's Problem".[102] Alternative logic is induction and abduction.[103]

Inability to individualize for each patient

A general problem with EBM is that it seeks to make recommendations for treatment that (on balance) are likely to provide the best treatment for most patients. However what is the best treatment for most patients is not necessarily the best treatment for a particular individual patient. The causes of disease, and the patient responses to treatment all vary considerably, and are affected for example by the individual's genetic make-up, their particular history, and by factors of individual lifestyle. To take these properly into account requires the clinical experience of the treating physician, and over-reliance upon recommendations based upon statistical outcomes of treatments given in a standardised way to large populations may not always lead to the best care for a particular individual.

Ulterior motives

An early criticism of EBM is that it will be a guise for rationing resources or other goals that are not in the interest of the patient.[104][105] In 1994, the American Medical Association helped introduce the "Patient Protection Act" in Congress to reduce the power of insurers to use guidelines to deny payment for a medical services.[106] As a possible example, Milliman Care Guidelines state they produce "evidence-based clinical guidelines since 1990".[107] In 2000, an academic pediatrician sued Milliman for using his name as an author on a practice guidelines that he stated were "dangerous" [108][109][110] A similar suit disputing the origin of care decisions at Kaiser has been filed.[111] The outcomes of both suits are not known.

Conversely, clinical practice guidelines by the Infectious Disease Society of America are being investigated by Connecticut's attorney general on grounds that the guidelines, which do not recognize a chronic form of Lyme disease, are anticompetitive.[112][113]

EBM not recognizing the limits of clinical epidemiology

EBM is a set of techniques derived from clinical epidemiology, but a common criticism is that epidemiology can show association but not causation. While clinical epidemiology has its role in inspiring clinical decisions if it is complemented with testable hypotheses on disease,[114] many critics consider that EBM is a form of clinical epidemiology which became so common in health care systems, and imposed such an empiricist bias on medical research, that it has undermined the notion of causal inference in clinical practice.[115] It is argued that it has even become condemnable to use common sense,[116] as was cleverly illustrated in a systematic review of randomized controlled trials studying the effects of parachutes against gravitational challenges (free falls).[117]

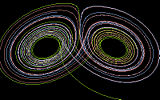

Complexity science

Complexity science and chaos theory are proposed as further explaining the nature of medical knowledge[118][119] and education[120].

Footnotes

- ↑ Sackett DL et al. (1996). "Evidence based medicine: what it is and what it isn't". BMJ 312: 71–2. PMID 8555924. [e]

- ↑ Evidence-Based Medicine Working Group (1992). "Evidence-based medicine. A new approach to teaching the practice of medicine. Evidence-Based Medicine Working Group". JAMA 268: 2420–5. PMID 1404801. [e]

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Glasziou, Paul; Strauss, Sharon Y. (2005). Evidence-based medicine: how to practice and teach EBM. Elsevier/Churchill Livingstone. ISBN 0-443-07444-5.

- ↑ Thier SL, Yu-Isenberg KS, Leas BF et al (2008). "In chronic disease, nationwide data show poor adherence by patients to medication and by physicians to guidelines". Manag Care 17: 48-52, 55-7. PMID 18361259. [e]

- ↑ Manheimer E et al. (2007). "Meta-analysis: acupuncture for osteoarthritis of the knee". Ann Intern Med 146: 868–77. PMID 17577006. [e]

- ↑ Assefi NP et al. (2005). "A randomized clinical trial of acupuncture compared with sham acupuncture in fibromyalgia". Ann Intern Med 143: 10–9. PMID 15998750. [e]

- ↑ Clancy CM, Cronin K (2005). "Evidence-based decision making: global evidence, local decisions". Health Affairs (Project Hope) 24: 151–62. DOI:10.1377/hlthaff.24.1.151. PMID 15647226. Research Blogging.

- ↑ Shojania KG, Grimshaw JM (2005). "Evidence-based quality improvement: the state of the science". Health Affairs (Project Hope) 24: 138–50. DOI:10.1377/hlthaff.24.1.138. PMID 15647225. Research Blogging.

- ↑ Fielding JE, Briss PA (2006). "Promoting evidence-based public health policy: can we have better evidence and more action?". Health Affairs (Project Hope) 25: 969–78. DOI:10.1377/hlthaff.25.4.969. PMID 16835176. Research Blogging.

- ↑ Foote SB, Town RJ (2007). "Implementing evidence-based medicine through medicare coverage decisions". Health Affairs (Project Hope) 26 (6): 1634–42. DOI:10.1377/hlthaff.26.6.1634. PMID 17978383. Research Blogging.

- ↑ Fox DM (2005). "Evidence of evidence-based health policy: the politics of systematic reviews in coverage decisions". Health Affairs (Project Hope) 24: 114–22. DOI:10.1377/hlthaff.24.1.114. PMID 15647221. Research Blogging.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Eddy DM (2005). "Evidence-based medicine: a unified approach". Health Affairs (Project Hope) 24: 9-17. DOI:10.1377/hlthaff.24.1.9. PMID 15647211. Research Blogging.

- ↑ Aberegg SK, O'Brien JM (2009). "The normalization heuristic: an untested hypothesis that may misguide medical decisions.". Med Hypotheses 72 (6): 745-8. DOI:10.1016/j.mehy.2008.10.030. PMID 19231086. Research Blogging.

- ↑ McDonald CJ (1996). "Medical heuristics: the silent adjudicators of clinical practice.". Ann Intern Med 124 (1 Pt 1): 56-62. PMID 7503478.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Haynes RB (2006). "Of studies, syntheses, synopses, summaries, and systems: the "5S" evolution of information services for evidence-based health care decisions". ACP J Club 145: A8. PMID 17080967. [e]

- ↑ Richardson WS, Wilson MC, Nishikawa J, Hayward RS (1995 Nov-Dec). "The well-built clinical question: a key to evidence-based decisions.". ACP J Club 123 (3): A12-3. PMID 7582737.

- ↑ Huang X, Lin J, Demner-Fushman D (2006). "Evaluation of PICO as a knowledge representation for clinical questions". AMIA Annu Symp Proc: 359–63. PMID 17238363. PMC 1839740. [e]

- ↑ Schardt C, Adams MB, Owens T, Keitz S, Fontelo P (2007). "Utilization of the PICO framework to improve searching PubMed for clinical questions". BMC Med Inform Decis Mak 7: 16. DOI:10.1186/1472-6947-7-16. PMID 17573961. PMC 1904193. Research Blogging.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 19.2 Ioannidis JP (2005). "Contradicted and initially stronger effects in highly cited clinical research.". JAMA 294 (2): 218-28. DOI:10.1001/jama.294.2.218. PMID 16014596. Research Blogging.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 Poynard T, Munteanu M, Ratziu V, Benhamou Y, Di Martino V, Taieb J et al. (2002). "Truth survival in clinical research: an evidence-based requiem?". Ann Intern Med 136 (12): 888-95. PMID 12069563.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 Hall JC, Platell C (1997). "Half-life of truth in surgical literature.". Lancet 350 (9093): 1752. DOI:10.1016/S0140-6736(05)63577-5. PMID 9413475. Research Blogging.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 Shojania KG, Sampson M, Ansari MT, Ji J, Doucette S, Moher D (2007). "How quickly do systematic reviews go out of date? A survival analysis.". Ann Intern Med 147 (4): 224-33. PMID 17638714.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 Shekelle PG, Ortiz E, Rhodes S, Morton SC, Eccles MP, Grimshaw JM et al. (2001). "Validity of the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality clinical practice guidelines: how quickly do guidelines become outdated?". JAMA 286 (12): 1461-7. PMID 11572738.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 24.2 Lasser KE, Allen PD, Woolhandler SJ, Himmelstein DU, Wolfe SM, Bor DH (2002). "Timing of new black box warnings and withdrawals for prescription medications.". JAMA 287 (17): 2215-20. PMID 11980521.

- ↑ Banks DE et al. (2007). "Decreased hospital length of stay associated with presentation of cases at morning report with librarian support". JMLA 95: 381–7. DOI:10.3163/1536-5050.95.4.381. PMID 17971885. Research Blogging.

- ↑ Lucas BP, Evans AT, Reilly BM, et al (2004). "The impact of evidence on physicians' inpatient treatment decisions". J Gen Intern Med 19 (5 Pt 1): 402–9. DOI:10.1111/j.1525-1497.2004.30306.x. PMID 15109337. Research Blogging.

- ↑ Rosenbloom ST, Giuse NB, Jerome RN, Blackford JU (January 2005). "Providing evidence-based answers to complex clinical questions: evaluating the consistency of article selection". Acad Med 80 (1): 109–14. PMID 15618105. [e]

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 McKibbon KA, Fridsma DB (2006). "Effectiveness of clinician-selected electronic information resources for answering primary care physicians' information needs". JAMIA 13: 653–9. DOI:10.1197/jamia.M2087. PMID 16929042. Research Blogging.

- ↑ Westbrook JI, Coiera EW, Gosling AS (2005). "Do online information retrieval systems help experienced clinicians answer clinical questions?". J Am Med Inform Assoc 12 (3): 315–21. DOI:10.1197/jamia.M1717. PMID 15684126. Research Blogging.

- ↑ DiCenso A, Bayley L, Haynes RB (2009). "ACP Journal Club. Editorial: Accessing preappraised evidence: fine-tuning the 5S model into a 6S model.". Ann Intern Med 151 (6): JC3-2, JC3-3. PMID 19755349. Full text from www.acpjc.org

- ↑ Patel MR et al. (2006). "Randomized trial for answers to clinical questions: evaluating a pre-appraised versus a MEDLINE search protocol". JMLA 94: 382–7. PMID 17082828. [e]

- ↑ U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Ratings: [Strength of Recommendations and Quality of Evidence. Guide to Clinical Preventive Services, Third Edition: Periodic Updates, 2000-2003. Hosted by Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Rockville, MD.

- ↑ Ioannidis JP et al. (1998). "Issues in comparisons between meta-analyses and large trials". JAMA 279: 1089–93. PMID 9546568. [e]

- ↑ 34.0 34.1 Dickersin K et al. (1992). "Factors influencing publication of research results. Follow-up of applications submitted to two institutional review boards". JAMA 267: 374–8. PMID 1727960. [e]

- ↑ Smith R (2005). "Medical journals are an extension of the marketing arm of pharmaceutical companies". PLoS Med 2: e138. DOI:10.1371/journal.pmed.0020138. PMID 15916457. Research Blogging.

- ↑ Melander H et al. (2003). "Evidence b(i)ased medicine--selective reporting from studies sponsored by pharmaceutical industry: review of studies in new drug applications". BMJ 326: 1171–3. DOI:10.1136/bmj.326.7400.1171. PMID 12775615. Research Blogging.

- ↑ Saint S et al (2000). "Journal reading habits of internists". J Gen Intern Med 15: 881–4. PMID 11119185. [e]

- ↑ Pitkin RM et al. (1999). "Accuracy of data in abstracts of published research articles". JAMA 281: 1110–1. PMID 10188662. [e]

- ↑ Lord, Charles, Ross, Lee, and Lepper, Mark (1979). 'Biased Assimilation and Attitude Polarization: The Effects of Prior Theories on Subsequently Considered Evidence',Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 37 (11): 2098-2109.

- ↑ Bergman DA, Pantell RH (May 1986). "The impact of reading a clinical study on treatment decisions of physicians and residents". J Med Educ 61 (5): 380–6. PMID 3701813. [e]

- ↑ (1981) "How to read clinical journals: I. why to read them and how to start reading them critically.". Can Med Assoc J 124 (5): 555-8. PMID 7471000. PMC PMC1705173. [e]

- ↑ Hayward RA, Kent DM, Vijan S, Hofer TP (2006). "Multivariable risk prediction can greatly enhance the statistical power of clinical trial subgroup analysis.". BMC Med Res Methodol 6: 18. DOI:10.1186/1471-2288-6-18. PMID 16613605. PMC PMC1523355. Research Blogging.

- ↑ Lin JW, Chang CH, Lin MW, Ebell MH, Chiang JH (2011). "Automating the process of critical appraisal and assessing the strength of evidence with information extraction technology.". J Eval Clin Pract. DOI:10.1111/j.1365-2753.2011.01712.x. PMID 21707873. Research Blogging.

- ↑ 44.0 44.1 (1979) "The periodic health examination. Canadian Task Force on the Periodic Health Examination.". Can Med Assoc J 121 (9): 1193-254. PMID 115569. PMC PMC1704686.

- ↑ 45.0 45.1 Levels of Evidence. Retrieved on 2007-12-31.

- ↑ National Library of Medicine. Publication bias. Retrieved on 2007-12-17.

- ↑ Glasziou P, Doll H (2007). "Was the study big enough? Two "café" rules (Editorial)". ACP J Club 147: A08. PMID 17975858. [e]

- ↑ Montori VM et al (November 2005). "Randomized trials stopped early for benefit: a systematic review". JAMA 294: 2203–9. DOI:10.1001/jama.294.17.2203. PMID 16264162. Research Blogging.

- ↑ Trotta, F et al. (2008) Stopping a trial early in oncology: for patients or for industry? Ann Oncol mdn042. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdn042

- ↑ Slutsky AS, Lavery JV (2004). "Data Safety and Monitoring Boards". N Engl J Med 350: 1143–7. DOI:10.1056/NEJMsb033476. PMID 15014189. Research Blogging.

- ↑ 51.0 51.1 Goodman SN (1999). "Toward evidence-based medical statistics. 1: The P value fallacy". Ann Intern Med 130: 995–1004. PMID 10383371. [e]

- ↑ Browner WS, Newman TB (1987). "Are all significant P values created equal? The analogy between diagnostic tests and clinical research". JAMA 257: 2459–63. PMID 3573245. [e]

- ↑ Goodman SN (1999). "Toward evidence-based medical statistics. 2: The Bayes factor". Ann Intern Med 130: 1005–13. PMID 10383350. [e]

- ↑ Ancker JS, Kaufman D (2007). "Rethinking health numeracy: a multidisciplinary literature review". DOI:10.1197/jamia.M2464. PMID 17712082. Research Blogging.

- ↑ Dubeau CE et al. (1986). "Premature conclusions in the diagnosis of iron-deficiency anemia: cause and effect". Med Decis Making 6: 169–73. PMID 3736379. [e]

- ↑ Coderre S et al. (2003). "Diagnostic reasoning strategies and diagnostic success". Med Educ 37: 695–703. PMID 12895249. [e]

- ↑ 57.0 57.1 Eddy DM, Clanton CH (1982). "The art of diagnosis: solving the clinicopathological exercise". N Engl J Med 306: 1263–8. PMID 7070446. [e]

- ↑ Gross CP et al. (2000). "Relation between prepublication release of clinical trial results and the practice of carotid endarterectomy". JAMA 284: 2886–93. PMID 11147985. [e]

- ↑ Juurlink DN et al. (2004). "Rates of hyperkalemia after publication of the Randomized Aldactone Evaluation Study". N Engl J Med 351: 543–51. DOI:10.1056/NEJMoa040135. PMID 15295047. Research Blogging.

- ↑ Beohar N et al. (2007). "Outcomes and complications associated with off-label and untested use of drug-eluting stents". JAMA 297: 1992–2000. DOI:10.1001/jama.297.18.1992. PMID 17488964. Research Blogging.

- ↑ Soumerai SB et al. (1997). "Adverse outcomes of underuse of beta-blockers in elderly survivors of acute myocardial infarction". JAMA 277: 115–21. PMID 8990335. [e]

- ↑ Hemingway H et al. (2001). "Underuse of coronary revascularization procedures in patients considered appropriate candidates for revascularization". N Engl J Med 344: 645–54. PMID 11228280. [e]

- ↑ Turner BJ, Laine C (2001). "Differences between generalists and specialists: knowledge, realism, or primum non nocere?". J Gen Intern Med 16: 422-4. DOI:10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016006422.x. PMID 11422641. Research Blogging. PubMed Central

- ↑ Rawson N et al. (2005). "Factors associated with celecoxib and rofecoxib utilization". Ann Pharmacother 39: 597-602. PMID 15755796.

- ↑ 65.0 65.1 De Smet BD et al. (2006). "Over and under-utilization of cyclooxygenase-2 selective inhibitors by primary care physicians and specialists: the tortoise and the hare revisited". J Gen Intern Med 21: 694-7. DOI:10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00463.x. PMID 16808768. Research Blogging.

- ↑ Carey T et al. (1995). "The outcomes and costs of care for acute low back pain among patients seen by primary care practitioners, chiropractors, and orthopedic surgeons. The North Carolina Back Pain Project". N Engl J Med 333: 913-7. PMID 7666878.

- ↑ McKibbon KA et al. (2007). "Which journals do primary care physicians and specialists access from an online service?". JMLA 95: 246-54. DOI:10.3163/1536-5050.95.3.246. PMID 17641754. Research Blogging.

- ↑ Tatsioni A, Bonitsis NG, Ioannidis JPA (2007) Persistence of contradicted claims in the literature. JAMA 298

- ↑ Majumdar S et al. (2001). "Influence of physician specialty on adoption and relinquishment of calcium channel blockers and other treatments for myocardial infarction". J Gen Intern Med 16: 351-9. PMID 11422631.

- ↑ Fendrick A et al. (1996). "Differences between generalist and specialist physicians regarding Helicobacter pylori and peptic ulcer disease". Am J Gastroenterol 91: 1544-8. PMID 8759658.

- ↑ Lewis C et al. (1991). "The counseling practices of internists". Ann Intern Med 114: 54-8. PMID 1983933.

- ↑ Turner B et al.. "Breast cancer screening: effect of physician specialty, practice setting, year of medical school graduation, and sex". Am J Prev Med 8: 78-85. PMID 1599724.

- ↑ Laupacis A et al. (1988). "An assessment of clinically useful measures of the consequences of treatment". N Engl J Med 318: 1728–33. PMID 3374545. [e]

- ↑ Rembold CM (1998). "Number needed to screen: development of a statistic for disease screening". BMJ 317: 307–12. PMID 9685274. [e]

- ↑ Tengs TO et al (1995). "Five-hundred life-saving interventions and their cost-effectiveness". Risk Anal 15: 369–90. PMID 7604170. [e]

- ↑ Maharaj R (2008). "Adding cost to NNT: the COPE statistic". ACP J. Club 148: A8. PMID 18170986. [e]

- ↑ Wright JC, Weinstein MC (1998). "Gains in life expectancy from medical interventions--standardizing data on outcomes". N Engl J Med 339: 380–6. PMID 9691106. [e]

- ↑ 78.0 78.1 Sackett DL (1989). "Rules of evidence and clinical recommendations on the use of antithrombotic agents.". Chest 95 (2 Suppl): 2S-4S. PMID 2914516.

- ↑ 79.0 79.1 Sackett DL (1986). "Rules of evidence and clinical recommendations on the use of antithrombotic agents". Chest 89: 2S–3S. PMID 3943408. [e]

- ↑ Sethi NK, Sethi PK (2008). "Evidence-based medicine vs medicine-based evidence". Ann. Neurol.. DOI:10.1002/ana.21354. PMID 18350575. Research Blogging.

- ↑ Vandenbroucke, JP (2008-03-01). "Observational research, randomised trials, and two views of medical science". PLoS Medicine 5 (3): e67 EP -. DOI:10.1371/journal.pmed.0050067. Retrieved on 2008-03-11. Research Blogging.

- ↑ Michaud G et al. (1998). "Are therapeutic decisions supported by evidence from health care research?". Arch Intern Med 158: 1665–8. PMID 9701101. [e]

- ↑ Ellis J et al. (1995). "Inpatient general medicine is evidence based. A-Team, Nuffield Department of Clinical Medicine". Lancet 346: 407–10. PMID 7623571. [e]

- ↑ Booth A. Percentage of practice that is evidence based?. Retrieved on 2007-11-15.

- ↑ Haynes RB (2006). "Of studies, syntheses, synopses, summaries, and systems: the "5S" evolution of information services for evidence-based healthcare decisions". Evidence-based Medicine 11: 162–4. DOI:10.1136/ebm.11.6.162-a. PMID 17213159. Research Blogging.

- ↑ 86.0 86.1 Atkins D et al (2004). "Grading quality of evidence and strength of recommendations". BMJ 328: 1490. DOI:10.1136/bmj.328.7454.1490. PMID 15205295. Research Blogging.

- ↑ Guyatt G, et al. (2006). "An emerging consensus on grading recommendations?". ACP J Club 144: A8–9. PMID 16388549. [e]

- ↑ 88.0 88.1 Hopayian K (2004). "Why medicine still needs a scientific foundation: restating the hypotheticodeductive model - part two.". Br J Gen Pract 54 (502): 402-3; discussion 404-5. PMID 15372724. PMC PMC1266186.

- ↑ Kaufmann SH (December 2005). "Robert Koch, the Nobel Prize, and the ongoing threat of tuberculosis". N. Engl. J. Med. 353 (23): 2423–6. DOI:10.1056/NEJMp058131. PMID 16339091. Research Blogging.

- ↑ 90.0 90.1 Hill AB (May 1965). "The Environment And Disease: Association Or Causation?". Proc. R. Soc. Med. 58: 295–300. PMID 14283879. PMC 1898525. [e]

- ↑ GRADE working group. Retrieved on 2007-11-23.

- ↑ Walach H et al. (2006). "Circular instead of hierarchical: methodological principles for the evaluation of complex interventions". BMC Med Res Methodol 6: 29. DOI:10.1186/1471-2288-6-29. PMID 16796762. Research Blogging.

- ↑ Diamond GA, Kaul S (2009). "Bayesian classification of clinical practice guidelines.". Arch Intern Med 169 (15): 1431-5. DOI:10.1001/archinternmed.2009.235. PMID 19667308. Research Blogging.

- ↑ National Library of Medicine. Clinical practice guidelines. Retrieved on 2007-10-19.

- ↑ 95.0 95.1 Mendelson D, Carino TV (2005). "Evidence-based medicine in the United States--de rigueur or dream deferred?". Health Affairs (Project Hope) 24: 133–6. DOI:10.1377/hlthaff.24.1.133. PMID 15647224. Research Blogging.

- ↑ Hersh W (2002). "Medical informatics education: an alternative pathway for training informationists". JMLA 90: 76–9. PMID 11838463. [e]

- ↑ Shearer BS et al. (2002). "Bringing the best of medical librarianship to the patient team". JMLA 90: 22–31. PMID 11838456. [e]

- ↑ Straus S et al. (2007). "Misunderstandings, misperceptions, and mistakes". Evidence-based medicine 12: 2–3. DOI:10.1136/ebm.12.1.2-a. PMID 17264255. Research Blogging.

- ↑ Straus SE, McAlister FA (2000). "Evidence-based medicine: a commentary on common criticisms". CMAJ 163: 837–41. PMID 11033714. [e]

- ↑ Goodman SN (2002). "The mammography dilemma: a crisis for evidence-based medicine?". Ann Intern Med 137: 363–5. PMID 12204023. [e]

- ↑ Upshur RE (2000). "Seven characteristics of medical evidence". J Eval Clin Pract 6: 93–7. PMID 10970003. [e]

- ↑ Vickers, J (2006). The Problem of Induction (Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy). Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved on 2007-11-16.

- ↑ Rapezzi C, Ferrari R, Branzi A (2005). "White coats and fingerprints: diagnostic reasoning in medicine and investigative methods of fictional detectives.". BMJ 331 (7531): 1491-4. DOI:10.1136/bmj.331.7531.1491. PMID 16373725. PMC PMC1322237. Research Blogging.

- ↑ Grahame-Smith D (1995). "Evidence based medicine: Socratic dissent". BMJ 310: 1126–7. PMID 7742683. [e]

- ↑ Formoso G et al. (2001). "Practice guidelines: useful and "participative" method? Survey of Italian physicians by professional setting". Arch Intern Med 161: 2037–42. PMID 11525707. [e]

- ↑ Pear, R. A.M.A. and Insurers Clash Over Restrictions on Doctors - New York Times. Retrieved on 2007-11-14.

- ↑ Evidence-Based Clinical Guidelines by Milliman Care Guidelines. Retrieved on 2007-11-14.

- ↑ Nissimov, R (2000). Cost-cutting guide used by HMOs called `dangerous' / Doctor on UT-Houston Medical School staff sues publisher. Houston Chronicle. Retrieved on 2007-11-14.

- ↑ Nissimov, R (2000). Judge tells firm to explain how pediatric rules derived. Houston Chronicle. Retrieved on 2007-11-14.

- ↑ Martinez, B (2000). Insurance Health-Care Guidelines Are Assailed for Putting Patients Last. Wall Street Journal.

- ↑ Colliver, V (1/07/2002). Lawsuit disputes truth of Kaiser Permanente ads. San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved on 2007-11-14.

- ↑ Warner, S (2/7/2007). The Scientist : State official subpoenas infectious disease group. Retrieved on 2007-11-14.

- ↑ Gesensway, D (2007). ACP Observer, January-February 2007 - Experts spar over treatment for 'chronic' Lyme disease. Retrieved on 2007-11-14.

- ↑ Djulbegovic B et al. (2000). "Evidentiary challenges to evidence-based medicine". Journal of evaluation in clinical practice 6: 99–109. PMID 10970004. [e]

- ↑ Charlton BG. [Book Review: Evidence-based medicine: how to practice and teach EBM by Sackett DL, Richardson WS, Rosenberg W, Haynes RB. http://www.hedweb.com/bgcharlton/journalism/ebm.html] Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice. 1997; 3:169-172

- ↑ Michelson J (2004). "Critique of (im)pure reason: evidence-based medicine and common sense". J Evaluation Clin Pract 10: 157–61. DOI:10.1111/j.1365-2753.2003.00478.x. PMID 15189382. Research Blogging.

- ↑ Smith GC, Pell JP (2003). "Parachute use to prevent death and major trauma related to gravitational challenge: systematic review of randomised controlled trials". BMJ 327: 1459–61. DOI:10.1136/bmj.327.7429.1459. PMID 14684649. Research Blogging.

- ↑ Sweeney, Kieran (2006). Complexity in Primary Care: Understanding Its Value. Abingdon: Radcliffe Medical Press. ISBN 1-85775-724-6. Book review

- ↑ Holt, Tim A (2004). Complexity for Clinicians. Abingdon: Radcliffe Medical Press. ISBN 1-85775-855-2. Book review, ACP Journal Club Review

- ↑ Fraser SW, Greenhalgh T (2001). "Coping with complexity: educating for capability". BMJ 323 (7316): 799–803. PMID 11588088. [e]

- Pages using duplicate arguments in template calls

- Pages using PMID magic links

- Pages using ISBN magic links

- Editable Main Articles with Citable Versions

- CZ Live

- Health Sciences Workgroup

- Articles written in American English

- Advanced Articles written in American English

- All Content

- Health Sciences Content

- Pages with too many expensive parser function calls